Gideon Mantell (1790-1852)

On February 3, 1790, English obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist Gideon Algernon Mantell was born. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of Iguanodon began the scientific study of dinosaurs. In 1822 he was responsible for the discovery of the first fossil teeth, and later much of the skeleton, of Iguanodon. Moreover, Mantell is also famous for his contributions on the Cretaceous of southern England. Well, the Cretaceous is a geologic period from ca. 145 to 66 million years ago. In the geologic timescale, the Cretaceous follows the Jurassic period and is followed by the Paleogene period of the Cenozoic era. It is the last period of the Mesozoic Era, and, spanning 79 million years, the longest period of the Phanerozoic Eon. But more important – at least for me when I was a kid – the Cretaceous also is famous for its dinosaurs.

“In the prosecution of these researches… extraneous fossils were no longer regarded merely as subjects of natural history, but as memorials of revolutions which have swept over the face of the earth, in ages antecedent to all human record and tradition.”

– Gideon Mantell, The Fossils of the South Downs; or Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex (1822)

Gideon Mantell – Youth and Education

Mantell was born in Lewes, Sussex, the child of Thomas Mantell, a shoemaker, and Sarah Austen. Raised in a small cottage in St. Mary‘s Lane with his two sisters and four brothers, he showed a particular interest in the field of geology already at young age. The Mantell children could not study at local grammar schools that were reserved for children of Anglican faith, because the elder Mantell was a follower of the Methodist church. Thus, Gideon was educated at a dame school in St. Mary‘s Lane, and learned basic reading and writing from an old woman, and subsequently by John Button, a philosophically radical Whig who shared similar political beliefs with Mantell‘s father.

At age 15, Mantell secured an apprenticeship with a local surgeon named James Moore in Lewes for a period of five years, in which he took care of Mantell‘s dining, lodging and medical issues. Mantell delivered Moore’s medicines, kept his accounts, wrote out bills and extracted teeth from his patients.When his father died in 1807, Mantell began to anticipate his medical education and taught himself human anatomy, followed by a formal medical education in London. He received his diploma as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1811.

A Freetime Geologist

Mantell returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the cholera, typhoid and smallpox epidemics, Mantell found himself quite busy attending to more than 50 patients a day and delivering between 200 and 300 babies a year. Although mainly occupied with running his busy country medical practice, he spent his little free time pursuing his passion, geology, often working into the early hours of the morning, identifying fossil specimens he found at the marl pits in Hamsey. In 1813, Mantell was elected as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London. Two years later, he published his first paper, on the characteristics of the fossils found in the Lewes area.

Iguanodon remains found near Maidstone

Inspired by Mary Anning

Inspired by Mary Anning‘s sensational discovery of a fossilized animal resembling a huge crocodile at Lyme Regis in Dorset, Mantell became passionately interested in the study of the fossilized animals and plants found in his area.[5] The fossils he had collected from the region, near The Weald in Sussex, were from the chalk downlands covering the county. The chalk is part of the Upper Cretaceous System and the fossils it contains are marine in origin. But by 1819, Mantell had begun acquiring fossils from a quarry, at Whitemans Green, near Cuckfield. He named the new strata the Strata of Tilgate Forest, after an historical wooded area and it was later shown to belong to the Lower Cretaceous.

A Puzzling Tooth

By 1820, he had started to find very large bones at Cuckfield, even larger than those discovered by William Buckland, at Stonesfield in Oxfordshire.[4] Then, in 1822, shortly before finishing his first book The Fossils of South Downs, while Mantell was visiting a patient, his wife Mary Ann took a short stroll as she waited for him, and when Mantell finished his house call, she presented him with a puzzling tooth. In fact, this account can’t be confirmed and there have been several conflicting accounts later. What’s certain is that the tooth was unlike anything Mantell had ever seen. It was typical of an herbivore. Could it belong to a mammal? Mantell was confident that it came from Mesozoic strata, and there were no Mesozoic mammals known to science in the early 1820s. Even today, there are few known Mesozoic mammals of significant size, and Mantell‘s tooth was huge.[2]

A Giant Herbivore

Mantell showed the teeth to other scientists but they were dismissed as belonging to a fish or mammal and from a more recent rock layer than the other Tilgate Forest fossils. The eminent French anatomist, Georges Cuvier,[6] identified the teeth as those of a rhinoceros. Cuvier‘s dismissal was a blow to Mantell‘s confidence, but ultimately he remained firm: this tooth, along with other remains he found, belonged to a giant herbivorous reptile from the Mesozoic strata. He surmised that the owner of the remains must have been at least 18m in length.

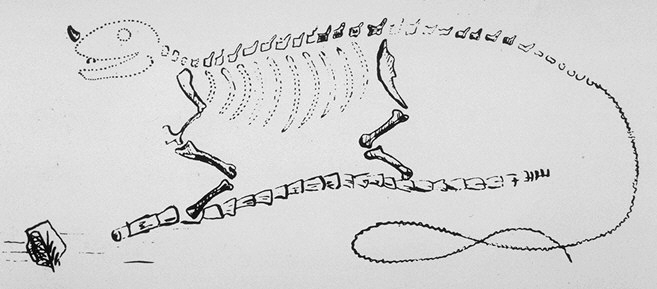

Mantell’s “Iguanodon” restoration based on the Maidstone Mantellodon remains, 1834

The Iguanodon

Years later, Mantell had acquired enough fossil evidence to show that the dinosaur’s forelimbs were much shorter than its hind legs, therefore proving they were not built like a mammal as claimed by Sir Richard Owen. Mantell went on to demonstrate that fossil vertebrae, which Owen had attributed to a variety of different species, all belonged to Iguanodon. He also named a new genus of dinosaur called Hylaeosaurus and as a result became an authority on prehistoric reptiles. In 1833, Mantell relocated to Brighton but his medical practice suffered. He was almost rendered destitute, but for the town’s council who promptly transformed his house into a museum. The museum in Brighton ultimately failed as a result of Mantell‘s habit of waiving the entrance fee. Finally destitute, Mantell offered to sell the entire collection to the British Museum, in 1838, and moved to Clapham Common in South London, where he continued his work as a doctor.

Later Life

In 1841 Mantell was the victim of a terrible carriage accident and suffered a debilitating spinal injury. Despite being bent, crippled and in constant pain, he continued to work with fossilised reptiles and published a number of scientific books and papers until his death in 1852 from an overdose of opium. At the time of his death Mantell was credited with discovering 4 of the 5 genera of dinosaurs then known.

David Hone, Social Behaviour in Dinosaurs, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gideon Mantell at Dinosaur Hunters

- [2] Biography of Gideon Mantell at StrangeScience

- [3] Biography of Gideon Mantell at Paleofiles

- [4] William Buckland and the Dinosaurs, SciHi Blog, March 12, 2013.

- [5] Mary Anning and her Marine Fossils, SciHi Blog, May 21, 2015.

- [6] George Cuvier and the Fossils, SciHi Blog

- [7] Gideon Mantell at Wikidata

- [8] The journal of Gideon Mantell, Hathi Trust

- [9] Scanned copy of The Fossils of the South Downs (1822)

- [10] Works written by or about Gideon Mantell at Wikisource

- [11] The Medals of Creation (1844) First Lessons in Geology and in the Study of Organic Remains by Gideon Mantell

- [12] David Hone, Social Behaviour in Dinosaurs, 2015, The Royal Institution @ youtube

- [13] Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 36. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- [14] Timeline of English Paleontologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Wheel’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #30 | Whewell's Ghost

You might be interested to know that one of Mantell’s sons emigrated to New Zealand, and I understand that the original iguanadon tooth is now in the Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa) along with other material gifted by the son. An image of the tooth can be found through the Te Papa collections website.