George Smith (1840-1876) from an engraving in The Illustrated London News, 1875

On March 26, 1840, English Assyriologist George Smith was born. Besides his pioneering work in Assyriology, he first discovered and translated the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest-known written work of literature. Moreover, its description of a flood, strikingly similar to the account in Genesis, had a stunning effect on Smith’s generation.

“Gilgamesh was called a god and a man; Enkidu was an animal and a man. It is the story of their becoming human together.”

― Herbert Mason, The Epic of Gilgamesh

If you like books and stories, you should have heard about the Epic of Gilgamesh, the adventures of the King of Uruk far back in the 18th century BCE. It’s one of the oldest stories ever told. And in the 1870s, English Assyriologist George Smith was the first to translate the poem, found in 1853 by native Assyrian and Christian Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam, into modern language. What Smith discovered in his translation really was astonishing. He read of a flood, a ship caught on a mountain and a bird sent out in search of dry land — the first independent confirmation of a vast flood in ancient Mesopotamia, complete with a Noah-like figure and an ark. It constituted one of the most sensational finds in the history of archaeology.

George Smith Background

George Smith was the son of a working-class family in Victorian England, born in Chelsea, London, and therefore limited in his ability to acquire a formal education. At age 14, he was apprenticed to a London-based publishing house to learn banknote engraving, at which he excelled. From his youth, he was fascinated with Assyrian culture and history. In his spare time, he read everything that was available to him on the subject. His interest was so keen that while working at the printing firm, he spent his lunch hours at the British Museum, studying publications on the cuneiform tablets that had been unearthed near Mosul in present-day Iraq by Austen Henry Layard, Sir Henry Rawlinson,[11] and their Iraqi assistant Hormuzd Rassam, during the archeological expeditions of 1840–1855.

The Assyriologist

Smith’s natural talent for cuneiform studies was first noticed by Samuel Birch, Egyptologist and Direct of the Department of Antiquities, who brought the young man to the attention of the renowned Assyriologist Sir Henry Rawlinson, the dominant figure in British cuneiform studies. As early as 1861, he was working evenings sorting and cleaning the mass of friable fragments of clay cylinders and tablets in the Museum’s storage rooms. In 1866 Smith made his first important discovery, the date of the payment of the tribute by Jehu, king of Israel, to Shalmaneser III. Sir Henry suggested to the Trustees of the Museum that Smith should join him in the preparation of the third and fourth volumes of The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia. Finally in early 1870, Smith was appointed Senior Assistant in the Assyriology Department of the British Museum.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

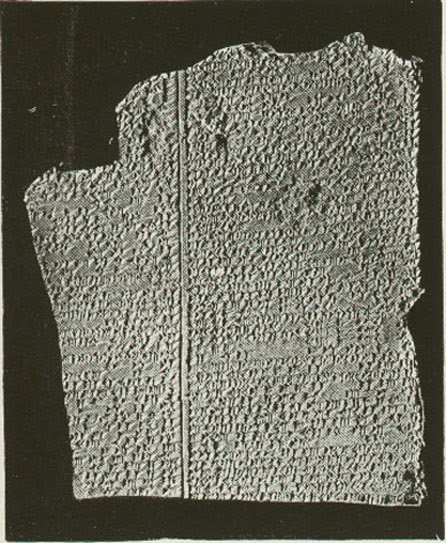

Smith’s earliest successes were the discoveries of two unique inscriptions early in 1867. The first, a total eclipse of the sun in the month of Sivan inscribed on Tablet K51, he linked to the spectacular eclipse that occurred on 15 June 763 BC. This discovery is the cornerstone of ancient Near Eastern chronology. The other was the date of an invasion of Babylonia by the Elamites in 2280 BC. In 1871, Smith published Annals of Assur-bani-pal transliterated and translated, and communicated to the newly founded Society of Biblical Archaeology a paper on The Early History of Babylonia. Worldwide fame came to Smith in 1872, with his translation of the Chaldaean account of the Great Flood, better known today as the eleventh tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known work of literature in the world.

The Deluge tablet of the Gilgamesh epic

Gilgamesh and Endiku

The first half of the Gilgamesh story relates the friendship between Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, and Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods as Gilgamesh’s peer to distract him from oppressing the people of Uruk. Together, they journey to the Cedar Mountain to defeat Humbaba, its monstrous guardian. Later they kill the Bull of Heaven, which the goddess Ishtar sends to punish Gilgamesh for spurning her advances. As a punishment for these actions, the gods sentence Enkidu to death. Gilgamesh’s distress at Enkidu’s death causes him to undertake a long and perilous journey to discover the secret of eternal life. He eventually learns that “Life, which you look for, you will never find. For when the gods created man, they let death be his share, and life withheld in their own hands“.

Further Excavations in Nineveh

The following January, Edwin Arnold, the editor of The Daily Telegraph, arranged for Smith to go to Nineveh at the expense of that newspaper and carry out excavations with a view to finding the missing fragments of the Flood story. However, Smith actually was able to discover some missing tablets, but moreover also some tablet fragment that recorded the succession and duration of the Babylonian dynasties. In November 1873 Smith again left England for Nineveh for a 2nd expedition and continued his excavations. An account of his work is given in Assyrian Discoveries,[5] published 1875. The rest of the year was spent in fixing together and translating the fragments relating to the creation, the results of which were published in The Chaldaean Account of Genesis,[9] which should become one of the best-selling books of its time. In March, 1876, the trustees of the British Museum sent Smith once more to excavate the rest of Assurbanipal‘s library. At Ikisji, a small village about sixty miles northeast of Aleppo, he fell ill with dysentery and died in Aleppo on August 19, 1876.

Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] David Damroch: Epic Hero, Smithsonian Magazine, 2007

- [2] Full text translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh by William Muss-Arnolt, 1901

- [3] Smith, The Chaldean account of Genesis Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection

- [4] George Smith in the Encyclopedia Britannica

- [5] George Smith, Assyrian Discoveries. An Account of Explorations and Discoveries on the Site of Nineveh, during 1873 and 1874. Adamant Media Corporation, 2001

- [6] George Smith (1878), Sayce, A.H (ed.), History of Sennacherib: Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions, London: Williams & Norgate

- [7] Robert S. Strother (1971). “The great good luck of Mister Smith”, in Saudi Aramco World, Volume 22, Number 1, January/February 1971

- [8] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Smith, George (Assyriologist)“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 261.

- [9] George Smith, The Chaldean Account of Genesis. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1876. From WisdomLib.

- [10] George Smith at Wikidata

- [11] Henry Rawlinson and the Mesopotamian Cuneiform, SciHi Blog

- [12] Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, The Royal Institution @ youtube

- [13] English Assyriologist Timeline via DBpedia and Wikidata