Gabriel Lippmann (1845-1921)

On August 16, 1845, Franco-Luxembourgish physicist and Nobel Laureate Gabriel Lippmann was born. He is best known for for his method of reproducing colors photographically based on the phenomenon of interference.

Gabriel Lippmann, Early Years

Gabriel Lippmann was the son of a Luxembourg Jewish family. His father, Isaïe managed the family glove-making business at the former convent in Bonnevoie. In 1848, the family moved to Paris where Lippmann was initially tutored by his mother, Miriam Rose (Lévy), before attending the Lycée Napoléon. Later he was admitted to the École Normale. In 1873, Lippmann was appointed to a government scientific mission visiting Heidelberg and Berlin, Germany to study methods for teaching science. He was able to specialize in electricity with the encouragement of Gustav Kirchhoff, receiving a doctorate with “summa cum laude” distinction in 1874. Lippmann returned to Paris to continue his studies at the Sorbonne and was appointed Professor of Mathematical Physics at the Faculty of Science in Paris in the 1880s. Later he should become Professor of Experimental Physics.

Experimental Physics

During his scientific career, Lippmann made numerous contributions to the fields of electricity, thermodynamics, optics and photochemistry. His studies of the relationship between electrical and capillary phenomena led to the development of his capillary electrometer.

Color Photography

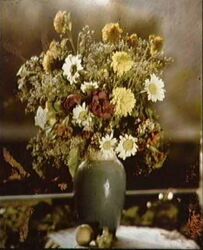

In the field of photography, Lippmann already had his general theory of his process for the photographic reproduction of color evolved by 1886. However, turning his theory into a practical execution caused a few difficulties. Color photography was probably first attempted in the 1840s and early pioneers include the American Daguerreotypist Levi Hill who created the quite complicated “Hillotype” process. Back then, the images required exposure times of several hours or sometimes the colors quickly began fading when the images were exposed to light for viewing, as it happened with the experiments by Edmond Becquerel. Lippmann’s interest to creating a method of fixing the colors of the solar spectrum on a photographic plate evolved in the 1880s. In 1891, he finally announced to the Academy of Sciences: “I have succeeded in obtaining the image of the spectrum with its colors on a photographic plate whereby the image remains fixed and can remain in daylight without deterioration.” By April 1892, Lippmann reported to have produced color images of a stained glass window, a group of flags, a bowl of oranges topped by a red poppy and a multicolored parrot and presented his theory of color photography using the interference method in two papers to the Academy of Sciences, one in 1894, the other in 1906.

A colour photograph made by Gabriel Lippmann in the 1890s

Lippmann’s vs Gabor’s Technique

Gabriel Lippmann’s method for the diffractive manifestation of color were mixed with Nobel Laureate Dennis Gabor’s technique.[3] The physics behind both methods can be understood on the same principle, as the wave nature of light is used which involves encoding the image field by interference, recording the structure in a photographic plate, and then reading out the image field again by sending light and getting it modulated in this structure. However, the result was different. While Gabriel Lippmann’s focus was to improve photography from black and white to color, Gabor’s holography extended photography from flat pictures to a three-dimensional image space.

The Nobel Prize in Physics

For their contributions, both, Dennis Gabor and Gabriel Lippmann were honored with the Nobel Prizes in Physics. Unfortunately, despite being highly innovative, Lippmann’s technique still did not overcome the handicap of high-resolution plates requiring exposure times from minutes to hours. Still, his abilty of taking photographs in natural colors stimulated and inspired future physicists and photographers. For example, the Lumière brothers developed a process based on transparent filters in three colors. This ‘autochrome‘ method prevailed into the 1930s until being replaced by present color photography technologies.

Further Achievements

His work on electrocapillarity is important from today’s perspective. He developed the capillary electrometer in 1872. Together with his work on electrowetting, he laid important foundations for the field of microfluidics. With the help of this method, tiny liquid droplets can be moved back and forth on surfaces. In addition to biotechnological microfluidic applications, displays (electronic paper) and lenses with electrically switchable focal length can also be produced in this way. Lippmann also invented a device (Coelostat or Zölostat), an auxiliary instrument in practical astronomy for tracking directionally fixed telescopes – in particular tower telescopes – of the daily rotation of the sky (1893). Gabriel Lippman died on 13 July 1921 aboard the steamer France while en route from Canada.[10]

Manfred Heiting, Learn to See Lecture 1 – What is an Original Photograph? [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Klaus Biedermann, “Lippmann’s and Gabor’s Revolutionary Approach to Imaging”, Nobelprize.org.

- [2] Gabriel Lippmann Biography at the Nobel Prize Page

- [3] The Holographic World of Dennis Gabor, SciHi Blog

- [4] The Lumière Brothers invented the Cinema, SciHi Blog

- [5] Gabriel Lippmann at Wikidata

- [6] Gustav Kirchhoff and the Fundamentals of Electrical Circuits, SciHi blog

- [7] The Holographic World of Dennis Gabor, SciHi Blog

- [8] Manfred Heiting, Learn to See Lecture 1 – What is an Original Photograph? UCLA College @ youtube

- [9] “Gabriel Lippmann”. Mathematics Genealogy Project.

- [10] “Gabriel Lippmann, Scientist, Dies at Sea“, The New York Times, 14 July 1921.

- [11] S. Katzir: The beginnings of piezoelectricity: A Study in Mundane Physics. Springer 2006

- [12] Lippmann, G. (1881). “Principe de la conservation de l’électricité”. Annales de chimie et de physique (in French). 24: 145.

- [13] Timeline of French Nobel Laureates, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Daniel John Mitchell at Cambridge has done some very interesting work on Lippmann:

bit.ly/1WyYVwl

http://www.hps.cam.ac.uk/people/mitchell.html

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #06 | Whewell's Ghost