François Rabelais (1494 – 1553)

Probably on April 9, 1553, French Renaissance writer, physician, Renaissance humanist, monk and Greek scholar François Rabelais passed away. Because of his literary power and historical importance, Western literary critics consider him one of the great writers of world literature and among the creators of modern European writing. His best known work is Gargantua and Pantagruel, telling the adventures of two giants, Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The work is written in an amusing, extravagant, and satirical vein, features much erudition, vulgarity and wordplay, and is regularly compared with the works of William Shakespeare [1] and James Joyce.[2]

“That’s all the glory my heart is after,

Seeing how sorrow eats you, defeats you.

I’d rather write about laughing than crying,

For laughter makes men human, and courageous.

BE HAPPY!”

– Francois Rabelais (1532–1564), Gargantua and Pantagruel, Introduction

Francois Rabelais – Early Years

Rabelais was probably born on La Devinière an estate near Chinon, in the province of Touraine, France, the youngest of three sons of the wealthy landowner and advocate Antoine Rabelais, seigneur de la Devinière († 1564), who successively held various offices in Chinon. His wife was Marie Catherine Dusouil. Rabelais entered his novitiate at the Franciscan monastery of La Baumette, Couvent des Cordeliers de la Baumette near Angers. Around the year 1511, Rabelais received his ordination sacraments. He was documented for 1520 as a friar in the Couvent des Puy-Saint-Martin Fontenay-le-Comte (Département Vendée). Here he had come into contact with the humanism radiating from Italy through an older confrere and had begun to learn ancient Greek. In addition, he established correspondence contacts with scholars, as evidenced by a letter dated 1521, apparently already his second, to the well-known humanist Guillaume Budé, the initiator of the Collège Royal founded in Paris in 1530. In the course of his Greek studies, Rabelais wrote a no longer extant translation of the first book of Herodotus‘ History of the Persian Wars around 1522.[3]

Greek Texts, Controversies, and Poitiers

In the 1520s Rabelais too, like so many contemporaries interested in humanism, was caught up in the reform ideas of Protestantism. In 1523, when all Greek studies were branded as a precursor to heresy by the reform-hostile Parisian theological faculty, the Sorbonne, Rabelais came into conflict with his Franciscan religious superiors because of his studies of ancient and especially Greek texts. Through the mediation of the Bishop of Poitiers, Geoffroy d’Estissac, who was also the abbot of a Benedictine monastery, he received papal permission to transfer to it in 1524, allowing him to leave the more anti-educational Franciscans in favor of the traditionally more education-friendly Benedictines. As his companion on journeys through the diocese, he visibly came into contact with people of various kinds and origins. He may also have attended law lectures at the University of Poitiers during these years. Around 1526, his first printed work appeared, a Latin verse epistle to a poet-lawyer friend from Ligugé.

Medical Sciences

From 1528 Rabelais is found in Paris, probably after intermediate stops at the universities of Bordeaux, Toulouse and Orléans. Apparently he had assumed the status of a diocesan priest, as which he was freer to continue his studies, now mainly of medicine, and to maintain learned contacts. In September 1530, he enrolled at the famous medical school of Montpellier, where Rabelais then earned a baccalaureate degree as early as November 1. Medicine at that time was almost purely a study of books, based on the writings of Hippocrates and Galenus. Rabelais was strongly influenced by the texts of Johannes Manardus, one of the leading physicians in Italy in the early 16th century.

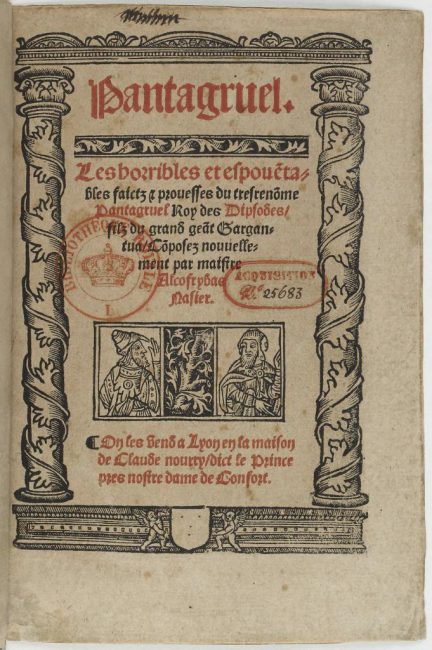

Title page of Pantagruel by Rabelais edited by Claude Nourry around 1530-1532.

Gargantua and Pantagruel

“His book is a riddle which may be considered inexplicable. Where it is bad, it is beyond the worst; it has the charm of the rabble; where it is good it is excellent and exquisite; it may be the daintiest of dishes.”

– Jean de La Bruyère on Rabelais’ book, cited in Catholic Encyclopedia of 1911.

In the summer of 1532, Rabelais lived in Lyon, where he practiced as a physician and at the same time published various learned works with the printer and publisher Sebastian Gryphius. However, he did not let himself be taken in by this, but also wrote a novel, which was also published in Lyon at the end of 1532: Les horribles et épouvantables faits et prouesses du très renommé Pantagruel, Roi des Dipsodes, fils du grand Gargantua. (The terrible and horrible adventures and exploits of the highly famous Pantagruel, king of the Dipsodes, son of the great giant Gargantua). The work was already recognizable by its title as a parody, especially of the genre of chivalric romance. After the success, Rabelais quickly followed up with Gargantua in a similar style, with the title La Vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel (The very terrible life of the great Gargantua, father of Pantagruel). The other volumes, printed considerably later, appeared under his real name and bear the sober titles Le tiers livre, Le quart livre and Le cinquième livre (“The Third Book”, “The Fourth Book”, “The Fifth Book”). Moreover, they are no longer in the tradition of chivalric romance parodies as their predecessors were. The two protagonists, Pantagruel, a young giant, and his father Gargantua, are still known today mainly by the French adjectives pantagruélique (“avoir un appétit pantagruélique” – to have a pantagruelic appetite) and gargantuesque (“un repas gargantuesque” – a gargantuan feast). Rabelais’ success was based on the fact that on the stylistic level he mixed playful irony and sarcasm, crude wit and pedantic erudition, puns and comically used real and fictitious quotations.

Illustration of Pantagruel for the Fourth Book in the Pantagruel and Gargantua series by François Rabelais, published in Oeuvres de Rabelais (Paris: Garnier Freres, 1873)

Jean de Bellay and Rome

At the end of 1532, Rabelais obtained a position at a Lyon hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Notre-Dame de la Pitié. In addition to his medical work, he frequented the intellectual circles of the city, which at that time were on a par with Paris. Probably in early 1534, he met Jean du Bellay, bishop of Paris and member of the crown council, a highly educated man who, on a diplomatic trip to Rome, stopped in Lyon and engaged him, the little older, as his personal physician and associate secretary. During his stay in Rome, Rabelais gained insight into conditions at the Holy See, where Pope Clement VII was maneuvering between the interests of France and Emperor Charles V, with whom he had been an involuntary ally since the conquest and sack of Rome by imperial Spanish troops in 1530. Back in Lyon, he edited an erudite Latin work by an Italian on the topography of ancient Rome. At the beginning of 1535 – Rabelais had just had another almanac printed – he left Lyon. At the end of October 1534, King Francis I had decided to take a stronger stand against the reformers, and to this end he had allowed further administrative measures to be taken. In these uncertain times, Rabelais was able to return to the service of Jean du Bellays and accompany him, who had been elevated to cardinal in May, to Rome once again.

Piedmont

At the beginning of 1537, since the pope had at the same time allowed him to remain a physician, he earned a doctorate in Montpellier and then lectured on the writings of Hippocrates. Once again he based his lectures on the Greek original and criticized the common Latin version as being faulty. In the summer he caused a sensation in Lyon when he dissected the corpse of a hanged man during a visit. In 1538 we find him in Aigues-Mortes with Jean du Bellay, who was here attending a meeting between King Francis I and Emperor Charles V, who had just negotiated an armistice in their long-running struggle for supremacy in Italy. At the end of 1539, Rabelais was recommended by Jean du Bellay to his ailing older brother Guillaume du Bellay, seigneur de Langey (1491-1543), a high military man who had been appointed governor of the northern Italian duchy of Piedmont, which was occupied by French troops. He was taken by him to Turin, the Piedmontese capital, where he wrote a Latin history of his campaigns under the title Stratagemata, but it is lost.

Later Years

After the death of King Francis I in 1547, Jean du Bellay once again traveled to Rome on a diplomatic mission, and Rabelais accompanied him. In transit, the latter gave a printer in Lyon the first eleven chapters of the new volume, which appeared in 1548 as Le Quart livre des faits et dits héroïques (The Quarter Book of Heroic Facts and Stories). He then completed the book in Rome. Here, in several satirical passages, he processed his observations from the politics of the Pope and thus indirectly supported the new French King Henry II, who sought the establishment of a national “Gallican” church. When the Quart livre was published as a whole in early 1552, now in Paris, the attitude of the rulers changed. The king and the pope had come to terms, and criticism of the latter was no longer welcome. Accordingly, the Sorbonne did not hesitate to condemn the book. As a result, the Paris Parlement also banned the work. However, the ban did not diminish the success of the book. After this, nothing more is known of him. Apparently, however, he had been working on another volume of continuations until shortly before his death in April 1553. This was brought to a conclusion by an unknown hand, probably on the initiative of his printer. It was published in 1563 under the title Le cinquième livre and was included in the complete editions of the cycle that began to appear shortly after the author’s death and continued to appear with great regularity.

Reception of Rabelais’ Literary Work

His novels were probably used by the contemporary reading public as a source of amusement at a time when there was little to laugh about in the face of a reality dominated by enormous religious and ideological polarization. This polarization reached into the family, caused an increasing intolerance of the sectarian parties and their propagandists, and led to an increasing brutalization of the people. Today, Rabelais is considered to be the greatest French author of the 16th century, one of the greats of French literature in general, and especially the figurehead of the morally often incorrect but popularly cheerful “esprit gaulois” or “rabelaisien,” even though his language has become archaic and his puns and allusions often barely comprehensible. Rabelais also left a tradition at the University of Montpellier’s Faculty of Medicine: no graduating medic can undergo a convocation without taking an oath under Rabelais’s robe. Further tributes are paid to him in other traditions of the university, such as its faluche, a distinctive student headcap styled in his honour with four bands of colour emanating from its centre.

French Passions: Simon McBurney on Rabelais, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Brush Up Your Shakespeare, SciHi Blog

- [2] James Joyce and Literary Modernism, SciHi Blog

- [3] Herodotus of Harlicarnassus – the Father of History, SciHi Blog

- [4] Gargantua and Pantagruel at Project Gutenberg, translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and illustrated by Gustave Doré.

- [5] Bowen, Barbara C. (1998). Enter Rabelais, Laughing. Vanderbilt University Press.

- [6] Works by or about François Rabelais at Internet Archive

- [7] Frame, Donald Murdoch; Rabelais, François (1999). The complete works of François Rabelais. Berkeley: University of California Press

- [8] François Rabelais Museum on the Internet (French)

- [9] French Passions: Simon McBurney on Rabelais, on Culturetheque IFRU at youtube

- [10] Georges Bertrin (1911). “The Catholic Encyclopedia: François Rabelais”. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [11] Francois Rabelais at Wikidata

- [12] French Passions: Simon McBurney on Rabelais, Culturetheque IFRU @ youtube

- [13] Timeline for Francois Rabelais, via Wikidata