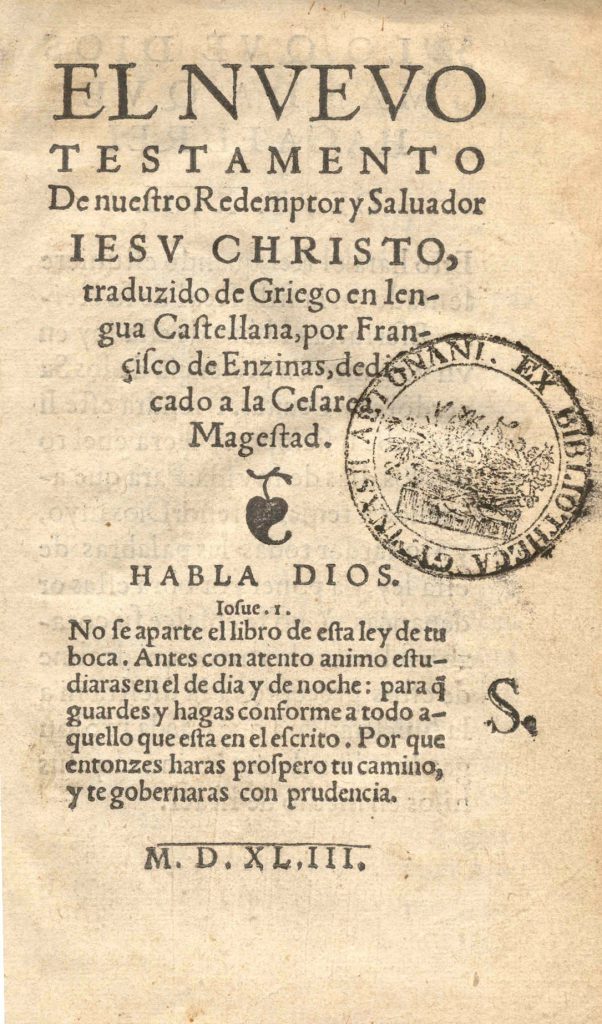

The New Testament translated by Enzinas, published in Antwerp (1543)

On December 30, 1552, classical scholar, translator, author, and Protestant apologist of Spanish origin Francisco de Enzinas, also known by the humanist name Francis Dryander, passed away. De Enzinas was the first to translate the New Testament from Greek to Spanish.

Early Years

Francisco de Enzinas was born in Burgos, Spain, probably on 1 November 1518, as one of ten children of the successful wool merchant Juan de Enzinas and his wife Ana, who died early (probably in 1527). His father married a second time in 1528 a Beatriz de Santa Cruz, who came from an influential family of Burgos.

Enzinas was sent to the Low Countries around 1536 for commercial training, but on 4 June 1539 he enrolled at the Collegium Trilingue of Louvain. There he fell under the spell of humanist scholarship as popularized by Desiderius Erasmus. Around that time he developed an acquaintance with the Polish Reformer Jan Łaski.

A brother, Diego de Enzinas, studied with him at the Collegium Trilingue and collaborated on a Spanish edition of the 1538 Catechism of John Calvin and the Freedom of the Christian Man by Martin Luther, printed at Antwerp in 1542. Diego was burned at the stake by the Roman Inquisition in 1547.

The Translation of the New Testament

In the summer of 1541 Francisco de Enzinas travelled to Paris to visit his relative Pedro de Lerma, who died in August of the same year. On 27 October 1541, he enrolled at the University of Wittenberg. His desire to study there with the famed hellenist Philip Melanchthon was an extension of his admiration for Erasmus. In Melanchthon’s house, Enzinas finished a translation of the New Testament into Spanish. He took it to Antwerp to be printed by Steven Mierdman in 1543. Following an interview with the Emperor Charles V, he was arrested by order of the Emperor’s confessor, Pedro de Soto. An attempt to confiscate the printed copies of the New Testament was only partly successful.

Dire Consequences

Enzinas escaped from the Vrunte prison in Brussels in February 1545. He made his way back to Wittenberg and wrote an account of his adventures, titled De statu Belgico et religione Hispanica, better known as his Mémoires. At the beginning of 1546, he learned from Spain that at the instigation of the imperial confessor de Soto, not only his legacy was to be frozen, but his family was also to be banned if Francisco did not go to Italy. Franciscos friend Juan Díaz, Spaniard and Protestant like him, suggested a meeting in Nuremberg; on 27 March Díaz was murdered in Neuburg an der Donau at the instigation of his own brother Alfonso. The next year in Basel, Enzinas edited and published an account of the murder of Juan Díaz, the Historia vera, which became a best seller in the overheated religious atmosphere of the day.

In 1547 Francisco de Enzinas made another journey through Switzerland and in the same year printed his Spanish translation of Plutarchs Kimon and Lukullus in Basel. There he also received the news that his brother Diego had been burned as a heretic in Rome. He gave up his residence in Basel and moved to Strasbourg because he no longer felt safe in Switzerland.

More Translations of the Classics

In March 1548, Enzinas married fellow religious exile Margaret Elter, a native of Guelders. Soon after, the couple moved to England at the urging of Martin Bucer, the reformer of Strasbourg, who also had set his sights on the relative safety of Edward VI’s realm. Thomas Cranmer took the couple into his palace at Lambeth and soon afterward appointed Enzinas to teach Greek at Cambridge to cover an extended absence of Regius Professor of Greek John Cheke. Francisco de Enzinas pushed ahead with his translations into Spanish with Plutarch, Lucian, and Livy, which were printed in Straßbourg in 1550. Thewre, Enzinas founded a publishing house for Spanish publications in 1551.

In 1552 the family caught the plague that was rampant in Strasbourg. Francisco de Enzinas died on 30 December 1552, only 34 years old; his wife died of the epidemic shortly afterwards on 1 February 1553.

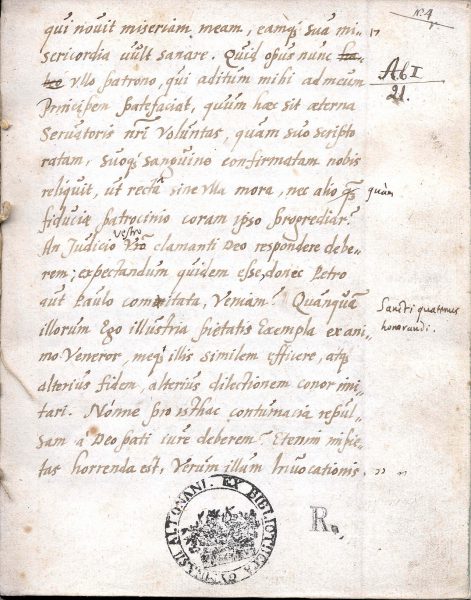

The first page of the (incomplete) Altona manuscript of the Historia de statu Belgico by Francisco de Enzinas, 1545 (N. 4r; p. 17)

Native Language Translations of the New Testament

Enzinas’s New Testament had a marked influence on subsequent translations, of which the most important was the Reina-Valera version, still the standard Bible of the Protestant Spanish-speaking world. When Stephan Mierdman accepted Francisco de Enzinas’ order to print the Spanish version of the New Testament in Antwerp in 1543, he violated the Roman Church’s sole claim to the Holy Scripture and its interpretation on the basis of only one canonized Latin version, the Vulgate. Translations into the national languages were not only suppressed by the Roman Church in the 16th century, but also persecuted; they were regarded as the cause of heresy, the controls were strict. Martin Luther would not have been unscathed by his translation of the Bible into German without his princely protection. Declaring this prohibition inadmissible was one of the motives of the Reformation.

A print of the Historia de statu Belgico et religione Hispanica during Francisco de Enzinas’ lifetime is not known, a handwritten record is not preserved. There are two handwritten copies, which presumably were commissioned by de Enzinas immediately after completion of the transcript in July 1545 in Wittenberg. Mention of names and events documented elsewhere makes this autobiographical typeface a unique historical source. In addition, the Historia also has literary traits, for example in its changing dynamics, dialogues and the presence of the narrator of the first-person.

El Nuevo Testamento is the leitmotif of the narrative; the reactions of the Spanish Inquisition to this publication presented in the Historia illustrate how much the Roman Church must have feared the spread of writings through the expanding printing of books and the distribution of, in particular, national-language prints, so that it followed readers and writers alike.

Robert Alter, “The Challenge of Translating the Bible”, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Francisco de Enzinas, Spanish Scholar, at Britannica Online

- [2] Nuevo Testamento traducido por Francisco de Enzinas, 1543, at Archive.org

- [3] Francisco de Enzinas at Wikidata

- [4] Martin Luther – Iconic Figure of the Reformation, SciHi Blog

- [5] Francisco de Enzinas at Post Reformation Digital Library

- [6] Memoires de Francisco Enzinas, digitized at HathiTrust

- [7] Robert Alter, “The Challenge of Translating the Bible”, Maxwell Institute Guest Lecture—January 29, 2020, Maxwell Institute @ yoyutube

- [8] Timeline of Bible Translators, via Wikidata

Pingback: ExecutedToday.com » 1547: Diego de Enzinas, Spanish Protestant