Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 15 April 1446), photo: I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On April 15, 1446, Italian Renaissance architect, designer, sculptor, and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi passed away. He is considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer. In 1421, Brunelleschi became the first person to receive a patent in the Western world. He is most famous for designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

Filippo Brunelleschi – Early Years

Filippo Brunelleschi was the son of the wealthy Florentine notary Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi and Giuliana degli Spini. After training as a goldsmith, in 1398 he enrolled in the Florentine guild responsible for this craft (Arte di Por Santa Maria); in 1404 he is listed there as “maestro”.

In the 1401 competition for the commission of another bronze portal for the Baptistery, Filippo Brunelleschi submitted a design, but it was rejected. The commission went to his competitor, the equally young Lorenzo Ghiberti. Between 1410 and 1420, Filippo Brunelleschi carved and polychromed a crucifix for the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, where it is now displayed in the Cappella Gondi. Giorgio Vasari‘s Vita of the Artist (1568)[1] states that it was created by Brunelleschi to surpass Donatello‘s crucifix for the Franciscan church of Santa Croce because the latter had “nailed a peasant to the cross” (“aveva messo un contadino in croce”)[2].

The Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

In 1418 Brunelleschi took part in the public competition to find a solution for the still missing dome of Santa Maria del Fiore and was able to prevail with his design against Lorenzo Ghiberti. Although the Opera del Duomo appointed both of them as equal construction supervisors, Brunelleschi took over the sole direction of the project while the work was still in progress. In 1436, the dome of the cathedral, built as an octagonal double-shell structure, was completed.

Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence, photo: Fczarnowski, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As early as 1419, Brunelleschi was commissioned by the Guild of Silk Weavers and Goldsmiths (Arte di Por Santa Maria) to build a foundling hospital, the Ospedale degli Innocenti, in the Piazza Santissima Annunziata. In the following years he designed the Cappella Barbadori in the church of Santa Felicità (1420), the hall building at the Palazzo di Parte Guelfa (begun in 1420, unfinished) and – for the Medici – the sacristy of San Lorenzo (1421-1428). In the course of the redesign of the chancel area of San Lorenzo, the nave of the church was also rebuilt starting in the 1420s; whether the design follows a model by Brunelleschi is disputed among art scholars.

Santo Spirito church, inside view, in Florence Italy, photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Begun in 1434, the unfinished church of Santa Maria degli Angeli has an octagonal plan; the interior is surrounded by a ring of chapels. In 1444, as Brunelleschi’s last major project, the long-planned new construction of the church of Santo Spirito began.

The Discovery of Linear Perspective

The alleged discovery of linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi can be traced back to Antonio di Tuccio Manetti’s description in his Vita, which was not written until the 1470s – decades after Brunelleschi’s death. According to Manetti, Brunelleschi used two panels of the Piazza San Giovanni and the Piazza della Signoria to demonstrate his discovery. In art historical research, several attempts have been made to reconstruct the described process. Central projection is used in descriptive geometry to produce descriptive images of spatial objects. In contrast to parallel projection, in which parallel rays are used to project onto a plane (image table), linear perspective or point-projection perspective uses rays (straight lines) through a fixed point O, the eye point. The central projection produces images as they are produced when seeing with one eye at the eye point. Whereas parallel projection maps parallel lines to just such lines, central projection or central perspective maps parallel lines that are not parallel to the image plane to lines that intersect at a point, the vanishing point. Central projections reproduce the spatial impression of an object much better than a parallel projection. This revolutionized painting and opened the way for the naturalistic styles of Renaissance art.[3]

The Delivery of the Keys fresco, 1481–1482, Sistine Chapel, by Perugino (1481–1482), features both linear perspective and Brunelleschi’s architectural style

A Modern Engineer

Brunelleschi was also an engineer and inventor of machines and apparatus. During the construction of the dome of the Florentine Cathedral, for example, he invented a change-speed gearbox for the large wooden crane that transported the building materials upwards, which made the rehitching of work animals superfluous. Until then, the crane’s hoist had been driven by a horse engine, and the animals always had to be re-harnessed for the up and down movements of the basket, which was time-consuming. In this way, Brunelleschi was able to considerably shorten the construction time on the dome. In 1421 Brunelleschi was granted the exclusive right to build a ship with a lifting device for transporting marble for three years.

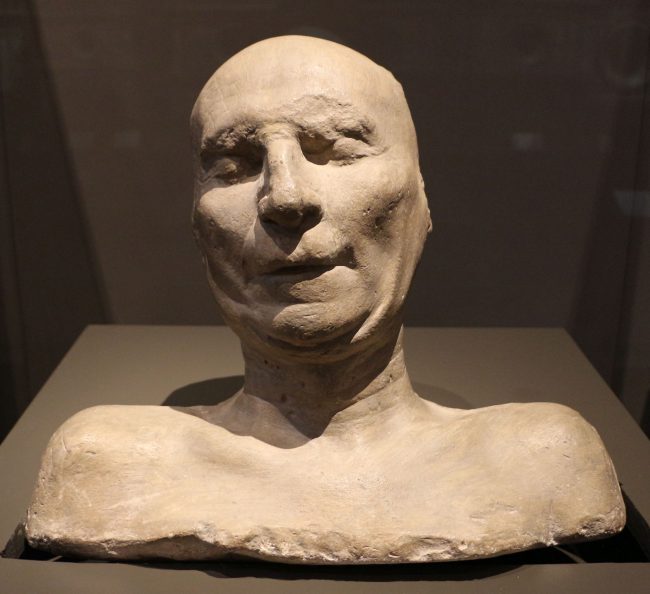

Death mask of Filippo Brunelleschi at Museo dell’Opera del Duomo (Florence), photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Death

Filippo Brunelleschi died on April 15, 1446 in Florence and was buried in the church of Santa Maria del Fiore. His adopted son Andrea Cavalcanti (Il Buggiano) took the death mask from him, which is still preserved today. It was the model for the portrait of Brunelleschi executed in 1447-1448 in the marble epitaph placed in his honor by the Commune in the Duomo. Brunelleschi’s tomb, which remained unknown for centuries, was rediscovered in July 1972.

Vida Hull, ARTH 2020/4037 Italian Renaissance Architecture: Brunelleschi, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Giorgio Vasari and his Foundations of Art-Historical Writing, SciHi Blog

- [2] Giorgio Vasari: Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1568. Eds. Rosanna Bettarini, Paola Barocchi. Vol 3. Sansoni, Florenz 1971.

- [3] Edgerton, Samuel Y (2009). The Mirror, the Window, and the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- [4] Meek, Harold (2010). “Filippo Brunelleschi”. Grove Art Online.

- [5] King, Ross (2001). Brunelleschi’s Dome: The Story of the great Cathedral of Florence. New York: Penguin.

- [6] Prager, Frank D. (1950). “Brunelleschi’s Inventions and the “Renewal of Roman Masonry Work”“. Osiris. 9: 457–554.

- [7] Vereycken, Karel, “The Secrets of the Florentine Dome”, Schiller Institute, 2013.

- [8] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Filippo Brunelleschi”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- [9] Filippo Brunelleschi at Wikidata

- [10] Vida Hull, ARTH 2020/4037 Italian Renaissance Architecture: Brunelleschi, East Tennessee State University @ youtube

- [11] Timeline for Filippo Brunelleschi, via Wikidata and DBpedia