Émilie du Châtelet (1706-1749)

On December 17, 1706, French mathematician, physicist, and author Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, marquise du Châtelet was born. Her major achievement is considered to be her translation and commentary on Isaac Newton‘s work Principia Mathematica, which still is the standard French translation of Newton‘s work today. Philosopher and author Voltaire, one of her lovers, once declared in a letter to his friend King Frederick II of Prussia that du Châtelet was “a great man whose only fault was being a woman“.

“To be happy, one must be free from prejudice; be virtuous; be well; have tastes and passions; be susceptible to illusion; for we owe most of our pleasures to illusion, and unfortunate is the one who loses it.”

– Emilie du Châtelet, Opuscules philosophiques et littéraires, 1769

Émilie du Châtelet – Childhood and Education

Émilie du Châtelet was born in Paris, the only daughter of six children to Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil, a member of the lesser nobility. At the time of du Châtelet’s birth, her father held the position of the Principal Secretary and Introducer of Ambassadors to King Louis XIV. He held a weekly salon on Thursdays, to which well-respected writers and scientists were invited. Du Châtelet’s education has been the subject of much speculation, but nothing is known with certainty. Among the acquaintances of Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil was Fontenelle, the perpetual secretary of the French Académie des Sciences. Recognizing Émilie’s early brilliance and abilities, he arranged for Fontenelle to visit and talk about astronomy with her when she was 10 years old. Her father arranged training for her in physical activities such as fencing and riding, and as she grew older, he brought tutors to the house for her to learn Latin, Italian, Greek and German as well as mathematics, literature, and science.

Bernoulli and Voltaire

In 1725, nineteen year old Émilie married the 15 year older Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont, conferring her the title of Marquise du Chastellet. Like many marriages among the nobility, the marriage was arranged. After the birth of her third child in 1733, Émilie resumed her mathematical studies in algebra and calculus with Moreau de Maupertuis, a member of the Academy of Sciences and student of Johann Bernoulli, one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family,[7] followed by prominent French mathematician, astronomer, geophysicist, and intellectual Alexis Clairaut, a mathematical prodigy. In the very same year, Émilie started a friendship and love affair with Voltaire,[8] whom she had met first already in 1729. Émilie invited Voltaire to live in her country house at Cirey-sur-Blaise, northeastern France, and he became her long-time companion — under the eyes of her tolerant husband. There she studied physics and mathematics and published scientific articles and translations.

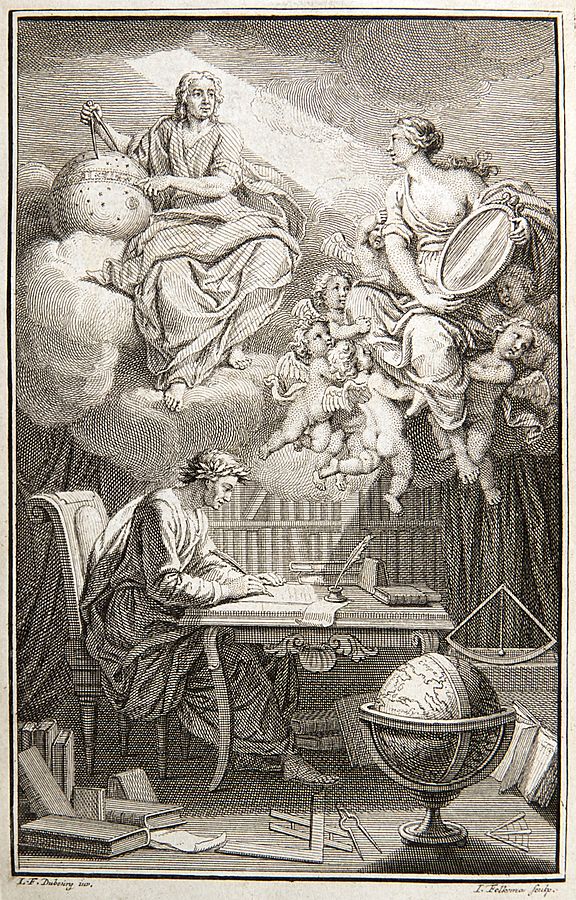

In the frontispiece to Voltaire’s book on Newton’s philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire’s muse, reflecting Newton’s heavenly insights down to Voltaire

Translating Newton into French

In the frontispiece to her translation of Newton,[9] du Châtelet is depicted as the muse of Voltaire, reflecting Newton’s heavenly insights down to Voltaire. A major contribution to physics was Émilie du Châtelet’s advocacy of kinetic energy. Although in the early 18th century the concepts of force and momentum had been long understood, the idea of energy as a transferrable currency between different systems, was still in its infancy. Inspired by theoretical work of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,[10] Émilie du Châtelet repeated and publicized an experiment originally devised by Willem ‘s Gravesande in which balls were dropped from different heights into a sheet of soft clay. Each ball’s kinetic energy – as indicated by the quantity of material displaced – was shown conclusively to be proportional to the square of the velocity. Earlier workers like Newton and Voltaire had all believed that “energy” was indistinct from momentum and therefore proportional to velocity. But, what Émilie du Châtelet is best remembered today, is her translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica into French, including her commentaries and her derivation of the notion of conservation of energy from its principles of mechanics. Today, du Châtelet’s translation of Principia Mathematica is still the standard translation of the work into French.

Final Years

From 1744 to 1748 she spent part of her time in Versailles together with Voltaire, who thanks to Madame de Pompadour had regained access to the farm. In the years 1748/49 she often lived with him in Lunéville Castle at the court of Stanislaus I. Leszczyński, the father-in-law of Louis XV and Polish ex-king, who had been compensated in 1735 by the Duchy of Lorraine. Here she began an affair with the courtier, officer and poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert. When she became pregnant, she succeeded, together with Saint-Lambert and Voltaire (who in turn had been in contact with a widowed niece since 1745), in convincing her husband that the child was his. On the night of 3 September 1749, she gave birth to a daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde, but died a week later, at Lunéville, from a pulmonary embolism.

Robyn Arianrhod, Émilie du Châtelet (1706-1749), [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] David Bodanis: Passionate Minds: The Great Enlightenment Love Affair, — a novel dealing with the life and love of Voltaire and his mistress, scientist Émilie du Châtelet.

- [2] David Bodanis: The Scientist whom History forgot, The Guardian, Aug 4, 2006.

- [3] Émilie du Châtelet at Biographies of Women Mathematicians

- [4] A Love Story — Voltaire and Émilie

- [5] Émilie du Châtelet at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [6] Émilie du Châtelet at Wikidata

- [7] How to calculate fortune – Jakob Bernoulli, SciHi Blog

- [8] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [9] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog

- [10] Let Us Calculate – the Last Universal Academic Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, SciHi Blog

- [11] Robyn Arianrhod, Émilie du Châtelet (1706-1749), Libori Summer School 2018, History of Women Philosophers @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of women in mathematics, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: year 2, Vol. #23 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #18 | Whewell's Ghost