Sir Edmond Halley (1656-1742)

©Klaus-Dieter Keller

On November 8, 1656, Sir Edmond Halley was born. The astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist, was best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley’s Comet.[9]

“Wherefore, if, according to what we have already said, it should return again about the year 1758, candid posterity will not refuse to acknowledge that this was first discovered by an Englishman.”

– Edmond Halley, as quoted in An Essay towards a History of the principal Comets that have appeared since the Year 1742 (1769), p. 49. Halley’s Comet reappeared on December 25, 1758.

Edmond Halley – Family Background

Edmond Halley was born in Haggerston in Middlesex, England to the family of Edmond Halley Sr, a wealthy soap maker. Halley was able to receive a proper education. He is believed to have been interested in mathematics from early age. Halley first studied at St Paul’s School where he presumably became enthusiastic about astronomy, and in 1673 he started attending The Queen’s College, Oxford.

Early Career

Halley’s success set in rather early. Still a college student, the young scientist traveled to Saint Helena, where he set up a sextant with telescopic sights to observe the stars of the southern hemisphere. He found out that the transit of the planet Mercury and the one by Venus could be used to calculate the absolute size of our solar system.[6] After publishing his results, Halley was now a widely discussed astronomer, he was awarded the Masters degree and elected as a fellow of the Royal Society, for which he had accomplished several tasks before. Between 1680 and 1681 Halley traveled to France and Italy and initiated scientific cooperation between the observatories of Greenwich and Paris. Between Calais and Paris, Halley observed for the first time the comet that was later named after him. From 1677 onwards, his calculations always pointed out the importance of Venus’ transits for determining the solar parallax.

In 1686, Halley made again major contributions to the field of astronomy through explaining solar heating with atmospheric motions, but also to the field of data visualization. His truly innovative charts and graphs were highly appreciated in the scientific community, wherefore his great reputation expanded.

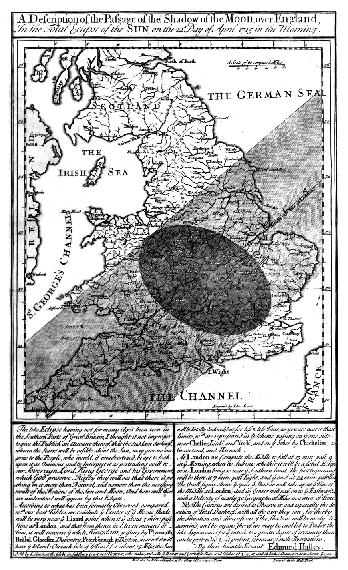

Halley’s map of the path of the Solar eclipse of 3 May 1715 across England

To improve his knowledge on the compass and terrestrial magnetism, Halley took command of the ship Paramour and went on a scientific voyage resulting in the publication of ‘General Chart of the Variation of the Compass‘ in 1701. This was the first such chart to be published and the first on which isogonic, or Halleyan lines appeared.

Halley’s Comet

In 1705, Halley published another groundbreaking work called ‘Synopsis Astronomia Cometicae‘ on observations of comet sightings between the years 1456 and 1682, which he determined to be one and the same comet. This was probably the work he is still best known for. His theory had been approved (unfortunately after his passing) and the comet was then named after Halley in honor to his great achievements. Halley’s comet is very special due to its appearance every 75 years and it also depicts the only short-period comet that is visible by the naked eye. The comet was also the first to be recognized as periodic, which Halley found out using Newton’s new laws on gravity.[7]

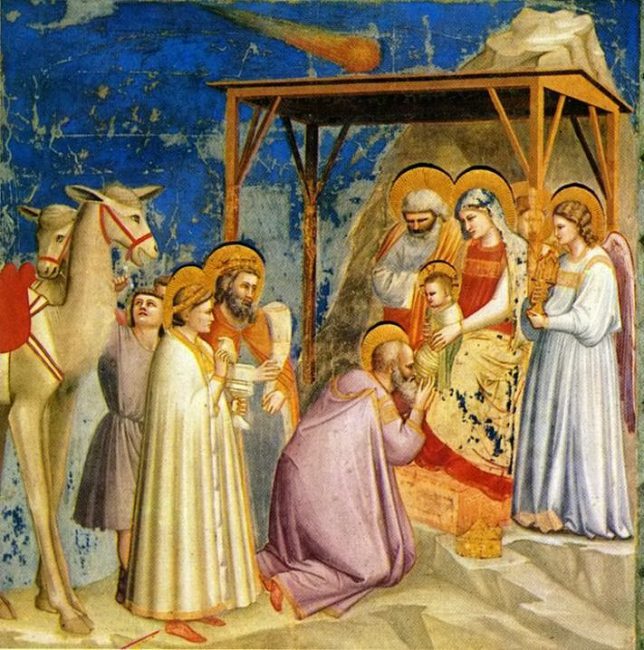

It was discovered over time that the comet had presumably been observed at least 25 times since 240 BC. One of the first pictorial representations of the comet can be found on the carpet of Bayeux (around 1070). The most famous is perhaps that of the painter Giotto di Bondone, who saw the comet in 1301 and used it as a model for the first realistic representation of a comet as the star of Bethlehem in the fresco Adoration of the Three Magi in the Cappella degli Scrovegni.

The Adoration of the Magi (circa 1305) by Giotto

The scientific career Halley’s continued, he discovered the proper motion of fixed stars, researched on scientifically dating the monument Stonehenge and finally became Astronomer Royal in 1720 as the successor of the famous John Flamsteed.[8]

Edmond Halley’s Impact

Edmond Halley made extraordinary contributions to several scientific fields in the 17th and 18th century, varying from astronomical research over discoveries in the area of geomagnetism to his invention of the diving bell and many other. His numerous works and visualizations were discussed for many years and Halley’s major achievements were honored by the Royal Society and many asteroids, comets, craters and mathematical methods were named after him.[9]

Newton’s Principia

In 1684 he discussed evidence of Kepler’s laws with Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke in a London coffee house. Since no solution was found, they decided to turn to Isaac Newton.[7] In August 1684, Halley went to Cambridge to see Newton, who had the solution to the problem in a drawer. Halley was able to convince him to complete the work. He also advanced the printing costs for the Principia.[10] This brought him into considerable financial difficulties, especially since the Royal Society not only did not contribute anything, but also paid his salary as its secretary not in cash, but in the form of books (De Historia Piscium).

Halley’s Comet: Earth’s Constant Companion, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Halley at ‘The Galileo Project’

- [2] Halley at the American Institute of Physics

- [3] Halley Biography by Stochastikon

- [4] Birth of Edmond Halley at History Today, 2006

- [5] Halley at Wikidata

- [6] David Rittenhouse and the Transit of Venus, SciHi Blog

- [7] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog

- [8] John Flamsteed – Astronomer Royal, SciHi Blog

- [9] Edmond Halley besides the Eponymous Comet, SciHi Blog

- [10] Sir Isaac Newton and the famous Principia, SciHi Blog

- [11] Halley’s Comet: Earth’s Constant Companion, Geographics @ youtube

- [12] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Edmond Halley“, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [13] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). “Edmond Halley”. Westminster Abbey.

- [14] Sharp, Tim (11 December 2018). “Edmond Halley: An Extraordinary Scientist and the Second Astronomer Royal”. Space.com.

- [16] Jones, Harold Spencer (1957). “Halley as an Astronomer”. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 12 (2): 175–192.

- [17]Lancaster-Brown, Peter (1985). Halley & His Comet. Blandford Press.

- [18] Edmond Halley Timeline via Wikidata