Sir David Brewster (1781-1868)

On July 10, 1817, Scottish physicist, mathematician, astronomer, inventor and writer Sir David Brewster received a patent for his kaleidoscope. “kaleidoscope” is derived from Ancient Greek and denotes something like “observation of beautiful forms.” It consists of a cylinder with mirrors containing loose, colored objects such as beads or pebbles and bits of glass. As the viewer looks into one end, light entering the other creates a colorful pattern, due to the reflection off the mirrors.

“Truth has no greater enemy than its unwise defenders, and no warmer friends than those who, receiving it in a meek and tolerant spirit, respect the conscientious convictions of others, and seek, in study and in prayer, for the best solution of mysterious and incomprehensible revelations.”

— David Brewster, In his Memoirs of the Life, Writings, and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: 1855)

David Brewster – Early Years

David Brewster was born at the Canongate in Jedburgh, Roxburghshire, as the third of six children to Margaret Key and James Brewster, the rector of Jedburgh Grammar School and a teacher of high reputation. Already as a child Brewster began to learn about physical science from his father’s manuscript notes from the University of Aberdeen. At the age of 12, David was sent to the University of Edinburgh, being intended for the clergy, from which he graduated as M.A. in 1800. He was licensed a minister of the Church of Scotland, but only preached from the pulpit on one occasion. In 1799 fellow-student Henry Brougham persuaded Brewster to study the diffraction of light. The results of his investigations were communicated from time to time in papers to the Philosophical Transactions of London and other scientific journals. The fact that other scientists – notably Étienne-Louis Malus and Augustin Fresnel [3] – were pursuing the same investigations contemporaneously in France does not invalidate Brewster‘s claim to independent discovery, even though in one or two cases the priority must be assigned to others. While he believed that he had disproved part of Newton’s explanation of the “inflexion” of light, Brewster did not then, or ever, abandon the emission theory of light.[1,4]

Literary and Scientific Efforts

Brewster’s income depended on his literary, rather than his scientific, efforts. He was a private tutor from 1799 to 1807; he edited the Edinburgh Magazine and Scots Magazine from 1802 to 1806, the Edinburgh Encyclopaedia from 1807 to 1830, and various scientific journals from 1819 to the end of his life.[1] Brewster is best noted for his experimental work in optics and polarized light. Polarized light has the property that all waves lie in the same plane. When light strikes a reflective surface at a certain angle, referred to as the polarizing angle, the reflected light becomes completely polarized. Brewster discovered a simple mathematical relationship between the polarizing angle and the refractive index of the reflective substance. This law is useful in determining the refractive index of materials that are opaque or available only in small samples.[2]

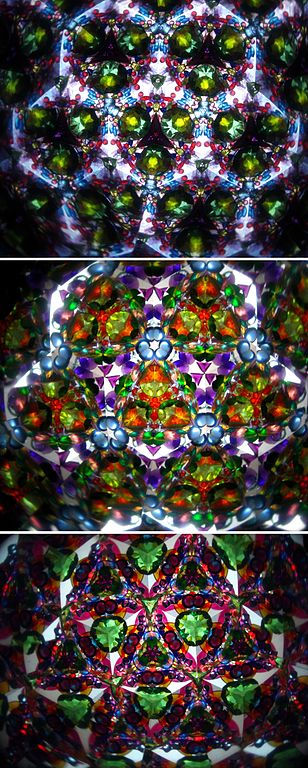

Patterns as seen through a kaleidoscope tube (wikipedia)

The Invention of the Kaleidoscope

Already in 1807 the degree of LL.D. was conferred upon Brewster by Marischal College, Aberdeen. In 1815 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, and received the Copley Medal. Among the non-scientific public, his fame spread more effectually by his invention in about 1815 of the kaleidoscope, for which actually there was a great demand in that time. Brewster chose renowned achromatic lens developer Philip Carpenter as the sole manufacturer of the kaleidoscope in 1817. Although Brewster patented the kaleidoscope in 1817, a copy of the prototype was shown to London opticians and copied before the patent was granted. As a consequence, the kaleidoscope became produced in large numbers, but yielded no direct financial benefits to Brewster. It proved to be a massive success with two hundred thousand kaleidoscopes sold in London and Paris in just three months.

The Kaleidoscope Principle

A kaleidoscope operates on the principle of multiple reflection, where several mirrors are placed at an angle to one another. Typically there are three rectangular mirrors set at 60° to each other so that they form an equilateral triangle. The 60° angle generates an infinite regular grid of duplicate images of the original, with each image having six possible angles and being a mirror image or not. As the tube is rotated, the tumbling of the coloured objects presents varying colours and beautiful symmetrical pattern created by the reflections. Brewster’s initial design was a tube with pairs of mirrors at one end, pairs of translucent disks at the other, and beads between the two. Initially intended as a scientific tool, the kaleidoscope was later copied as a toy.

Further Efforts

After the 1830’s Brewster directed his attention to such subjects as photography, stereoscopy, and the physiology of vision. At the same time he began to emphasize his writing rather than his editing.[1] Later in his life he served as President of the British Association; as one of the eight foreign associates of the Institute of France; and as Principal of the University of Edinburgh. David Brewster died in 1868.

How It’s Made: Kaleidoscopes, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Brewster, David.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com

- [2] David Brewster at Britannica Online

- [3] Augustin-Jean Fresnel and the Wave Theory of Light, SciHi Blog

- [4] Standing on the Shoulders of Giants – Sir Isaac Newton, SciHi Blog

- [5] David Brewster at Wikidata

- [6] Texts of and about David Brewster at Wikisource

- [7] Works by or about David Brewster at Internet Archive

- [8] How It’s Made: Kaleidoscopes, Science Channel @ youtube

- [9] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Brewster, Sir David“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 513–514.

- [10] Gordon, Margaret Maria (1881). The home life of sir David Brewster. D. Douglas.

- [11] Sir David Brewster (1858). The kaleidoscope, its history, theory and construction with its application to the fine and useful arts. J. Murray.

- [12] Timeline for David Brewster, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #48 | Whewell's Ghost