Cyrano de Bergerac (1619 – 1655)

On March 6, 1619, French novelist, playwright, epistolarian and duelist Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac was born. A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the seventeenth century. Today he is best known as the inspiration for Edmond Rostand‘s most noted drama Cyrano de Bergerac, which, although it includes elements of his life, also contains invention and myth. Cyrano – as he is usually simply called in literary history – is known today above all as a Romanesque drama or film character. However, the real significance of this author, who was active in many genres, lies in the fact that he can be regarded as one of the inventors of the science fiction novel and as a forerunner of the Enlighteners of the 18th century.

“Most men judge only by their senses and let themselves be persuaded by what they see. Just as the man whose boat sails from shore to shore thinks he is stationary and that the shore moves, men turn with the earth under the sky and have believed that the sky was turning above them. On top of that, insufferable vanity has convinced humans that nature has been made only for them, as though the sun, a huge body four hundred and thirty-four times as large as the earth, had been lit only to ripen our crab apples and cabbages. “

— Cyrano de Bergerac, The Other World (1657)

Family Background

Cyrano de Bergerac came from an originally middle-class family, but his grandfather, the Parisian sea fish merchant Savinien Cyrano, had bought the ennobling position of Royal Notary and Secretary in 1571 and in 1582 had acquired two estates not far from the capital, one of which belonged to a noble family de Bergerac who had immigrated from the southwest. Cyrano’s father, Abel de Cyrano, held a higher office at the Supreme Court of Paris, the Parlement, and was married under the noble title “écuyer” (actually “squire”). Cyrano himself considered himself unreservedly aristocratic and drew mostly “(de) Bergerac”. He spent his childhood as the fourth son of his parents, apparently largely separated from them, partly on one of the estates, partly with a village priest who gave him lessons. Later he visited the Jansenistic Collège de Beauvais in Paris. Apparently he was not an erudite and good pupil. He later caricatured the director of the college, a widely respected scholar, in a comedy.

Education and Military Service

After finishing school in 1638, he first led a dandy life. Apparently, however, the family’s financial situation deteriorated at the same time, as his father had already sold the goods in 1636. From 1638 Cyrano therefore hired himself out in a cloakroom regiment, which consisted mainly of gascognac cadets. He made a name for himself with his comrades as a warhorse and duelist, but he was also known as an author of verses. In 1639 and 1640 he took part with his regiment in the Franco-Spanish War, which took place at this time in the northwest of France. He was wounded twice, resigned from military service and returned to Paris.

Natural Philosophy and Dancing Lessons

In Paris he heard the lectures of the natural philosopher and researcher Pierre Gassendi in 1641.[1] Through him he got to know the theories of the ancient natural philosophers, but also the heliocentric world view of Copernicus,[2] Johannes Kepler [3] and Galileo Galilei.[4] In addition, he dealt with the writings of the philosopher René Descartes as well as with freethinking authors critical of religion. He was also interested in alchemy. At the same time he took dance and fencing lessons and moved in circles of young aristocrats, where a certain free spirit was cultivated. He also became increasingly associated with writers, including the well-known authors Paul Scarron and Tristan L’Hermite, as well as the lesser-known Charles d’Assoucy.

The Fronde

His financial situation during these years was precarious, because his father could not or did not want to support him. His health was also apparently not well, perhaps due to a syphilis infection. The small inheritance, which he received in 1648 when his father died, he quickly got through. During the political confusion of the Fronde (1648-1652), Cyrano was initially on the side of the insurgent people of Paris and the Paris Parliament, i.e. the opponents of the ruling Queen Mother Anna of Austria and her unloved minister, Cardinal Jules Mazarin. Against him he wrote the satirical poem Le Ministre d’État flambé, as well as anonymously some so-called Mazarinades, i.e. anti-Mazarin pamphlets. However, in 1651, after the Fronde had turned into a revolt of the high nobility, Cyrano changed sides, broke with his former friends, especially Scarron and D’Assoucy, and wrote a Lettre contre les Frondeurs in which he defended Mazarin’s absolutist policy.

The Other World

“I think the Moon is a world like this one, and the Earth is its moon.”

— Cyrano de Bergerac, The Other World (1657)

At the latest in 1650 he began the two-part novel that was to become his main work, L’autre monde (“The Other World“). In this novel a first-person narrator tells of his alleged journey to the moon and the sun and of his experiences and conversations with their inhabitants (e.g. the humoristically alienated biblical figures of the prophet Elijah and the patriarch Enoch, which he encounters on the moon). Here Cyrano places philosophical, naturalistic, religious and socio-political thoughts in the moons of the moon and sun dwellers, which were forbidden for a Frenchman of that time to express.

“Do you say it is incomprehensible that there is nothingness in the world and that we are partly composed of nothing? Well, why not? Is not the whole world enveloped by nothingness? Since you concede that point, admit as well that it is just as easy for the world to have nothingness within as without.”

— Cyrano de Bergerac, The Other World (1657)

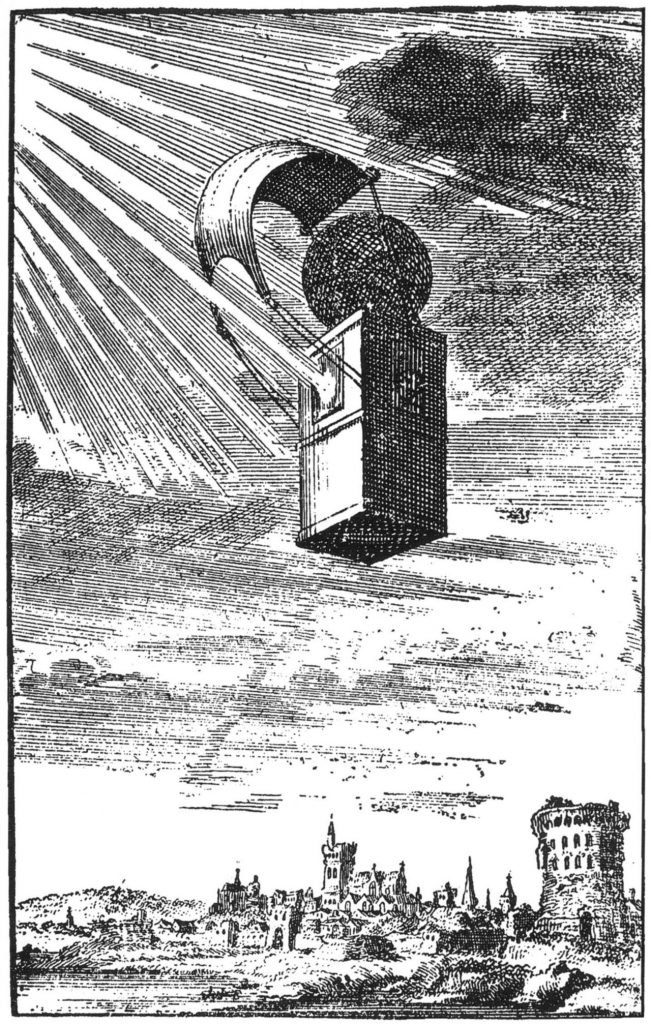

Copperplate engraving, Kupferstich (1662) zu L’histoire comique contenant les états et empires du soleil by Cyrano de Bergerac

Further Literary Works

In 1652 he entered the service of the Duke and high military Louis d’Arpajon as a kind of noble domestic. To him he dedicated his tragedy La Mort d’Agrippine (“The Death of Agrippina“), printed in 1654, a historical piece in the style of Pierre Corneille, in which he incorporated religion-critical tirades, which caused a great stir during the performance at the end of 1653. In 1654 he published a collective edition of smaller works written up to then, among them above all the comedy Le Pédant joué (“The Deceived Pedant“), written in prose, from which Molière drew for his penultimate piece, Les fourberies de Scapin, and the Lettres sur divers sujets, literary, predominantly satirical letters on various subjects, in which he allows himself, among other things, an open criticism of the Bible and the Church.

Accident or Assassination Plot

In the same year 1654 – his report of the moon journey was finished, the one of the sun journey still unfinished – he was struck by a tragic accident, which was however interpreted by some as an assassination attempt: Under unexplained circumstances a beam fell on his head in the city palace of his protector. He was first cared for in Paris by his sister Catherine, a nun, and later taken in by a cousin in Sannois. There he died a good year after the accident (whether from its consequences or from an illness, is not known) at the age of 36. He received a church burial, so he had arranged himself with the church before his death. He rests in the church Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul of Sannois.

Actor Benoît-Constant Coquelin as Cyrano de Bergerac.

Be Careful to Live Freely!

The two utopian novels were published posthumously in 1657 and 1662 respectively under the titles Les États et Empires de la Lune (“The States and Empires of the Moon“) and Les États et Empires du Soleil (“The States and Empires of the Sun“) by Henri Lebret, a friend of his youth. He erased several overly objectionable passages, which in the modern editions, however, are restituted from the preserved manuscripts. Most of the information known about Cyrano comes from the preface to Lebret. To this day the greeting of the moon dwellers “Songez à librement vivre” (“Be careful to live freely!“) is known and testifies to Cyrano de Bergerac’s free-thinking attitude.

Cyrano and Roxane

Most people will know Cyrano de Bergerac by the romantic story originally based on a play by the French poet Edmond Rostand. In 1897, Rostand published a play, Cyrano de Bergerac, on the subject of Cyrano’s life. This play, which became Rostand’s most successful work, revolves around Cyrano’s love for the beautiful Roxane, whom he is obliged to woo on behalf of a more conventionally handsome but less articulate friend, Christian de Neuvillette. The play has been made into operas and adapted for cinema several times and reworked in other literary forms and as a ballet.

Matt Duckworth, Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac”: An Introductory Lecture for English 1B, [10]

References and Further Reading

- [1] Pierre Gassendi and his Trials to reconcile Epicurean atomism with Christianity, SciHi Blog

- [2] Nikolaus Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model, SciHi Blog

- [3] And Kepler Has His Own Opera – Kepler’s 3rd Planetary Law, SciHi Blog

- [4] Galileo Galilei and his Telescope, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by Cyrano de Bergerac, via Wikisource

- [6] Works by or about Cyrano de Bergerac at Internet Archive

- [7] Cyrano de Bergerac, The Other World: Society and Government of the Moon – annotated English language edition

- [8] Cyrano de Bergerac (1889). A Voyage to the Moon. Translated by Archibald Lovell, Edited by Curtis Hidden Page. New York: Doubleday and McClure Co.

- [9] Cyrano de Bergerac at Wikidata

- [10] Matt Duckworth, Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac”: An Introductory Lecture for English 1B, Matt Duckworth @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of French Satirists, via DBpedia and Wikidata