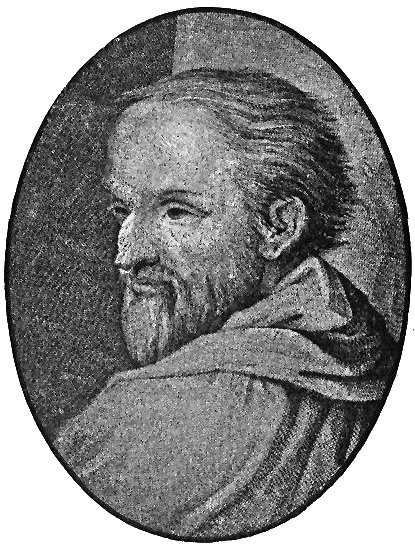

Antonio Allegri da Correggio (1489 – 1534)

On March 5, 1534, Antonio Allegri da Correggio, painter of the Italian High Renaissance, passed away. A master of chiaroscuro, he was responsible for some of the most vigorous and sensuous works of the 16th century. In his use of dynamic composition, illusionistic perspective and dramatic foreshortening, Correggio prefigured the Baroque art of the 17th century and the Rococo art of the 18th century.

Correggio’s Early Years

The birthplace of Correggio, after whom it is named, is near Reggio nell’Emilia in Italy. His father was a merchant. From 1503 to 1505 Correggio was apprenticed to Francesco Bianchi Ferrara in Modena. His earliest works show influences of classicism by artists such as Lorenzo Costa and Francesco Francia, which probably date back to this period. In 1506 Correggio was in Mantua, then he returned to Correggio, where he remained until 1510. The Adoration of the Child with Elizabeth and John is attributed to this period of his work, which seems to show influences from Costa and Mantegna. In 1514 he probably completed three tondi for the entrance of St. Andrea in Mantua. After returning to his home town he signed, now independent and increasingly famous, a contract for an altarpiece with the Madonna in the convent of St. Francis.

Correggio, Noli me tangere, ca. 1518

Success in Parma

In 1516 Correggio stayed in Parma, where he remained from then on by and large. Here he made friends with the mannerist Michelangelo Anselmi. In 1519 he married Girolama Francesca di Braghetis from Correggio. From this period are Madonna with Child and the young John the Baptist, Farewell of Christ to Mary and the Lost Madonna of Albinea. From the phase of his mature years comes the painting Noli me tangere (c. 1518, after others c. 1522-1525), already praised by Giorgio Vasari,[2] today in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, which from the possession of Emperor Charles V finally came into the hands of King Philip IV of Spain and in 1636 found its place in the sacristy of the Escorial.

Dome of the Cathedral of Parma, fresco with the “Assumption of the Virgin” by Antonio da Correggio, c. 1526

A Revolutionary Illusionist

Correggio’s first major commission was to decorate the ceiling of the private dining room of the Abbess of St. Paul in Parma (the Camera di San Paolo). Next he painted the vision of St. John in Patmos for the dome of San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma. Three years later, he decorated the dome of Parma Cathedral with a surprising Assumption of the Virgin Mary in Melozzo’s perspective (seen from bottom to top). Both works were revolutionary, illusionist dome decorations and strongly influenced later fresco painting (Cignani, Ferrari, Pordenone, Lanfranco, Baciccio), especially by the massing of spectators in a whirlpool, the apparent disappearance of the dome and the thrusting view up into divine infinity, as they are encountered again in Baroque painting.

Correggio, Danaë, c. 1530

Controversial Art

The starting point of Correggio’s art is controversial. Apart from Costa and Mantegna, it could have been influenced by Leonardo da Vinci,[2] Michelangelo [3] and Raphael [4] in his essential impressions of the Chiaroscuro (light-dark). Around 1518 he found his own style, which combines devotional expressions with almost baroque, lively movements. This also explains his great influence on baroque masters such as Reni, the Carracci and Barocci. Correggio’s panel paintings develop diagonal compositions, richly execute the painterly chiaroscuro and are rich in colour. His frescoes are particularly characterized by the boldness of the perspective view from below, by the mobility of the figures in air and light and by suggestive illusionary power.

Last Years and Legacy

Apart from his religious work, Correggio conceived a now famous series of paintings depicting the loves of Jupiter, as described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The opulent series was commissioned by Frederick the Great, probably to decorate his private Ovid room in his tea house. However, they were given to the visiting Roman Emperor Charles V and left Italy within a few years of their completion. Returning to his home town in later years, Correggio died there suddenly on 5 March, 1534. Correggio was remembered by his contemporaries as a shadowy, melancholic and introverted character. An enigmatic and eclectic artist, he appears to have emerged from no major apprenticeship. A half-century after his death Correggio’s work was well known to Vasari, who felt that he had not had enough “Roman” exposure to make him a better painter. In the 18th and 19th centuries, his works were often noted in the diaries of foreign visitors to Italy, which led to a reevaluation of his art during the period of Romanticism.

You might learn more about Correggio in the lecture of David Gariff, senior lecturer, National Gallery of Art in the 2019 Summer Sunday Lecture Series: Central Italian Painting, 1300-1520.

David Gariff, 2019 Summer Sunday Lecture Series: Central Italian Painting, 1300-1520, [8]

References and further reading:

- [1] Giorgio Vasari and his Foundations of Art-Historical Writing, SciHi Blog

- [2] Leonardo Da Vinci – the Prototype of a Renaissance Man, SciHi Blog

- [3] Michelangelo Buonarotti – the Renaissance Artist, SciHi Blog

- [4] Raphael and his famous School of Athens, SciHi Blog

- [5] 66 paintings by or after Antonio da Correggio at the Art UK site

- [6] Rossetti, William Michael (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [7] Correggio at Wikidata

- [8] David Gariff, 2019 Summer Sunday Lecture Series: Central Italian Painting, 1300-1520, National Gallery of Art @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of Correggio, via Wikidata