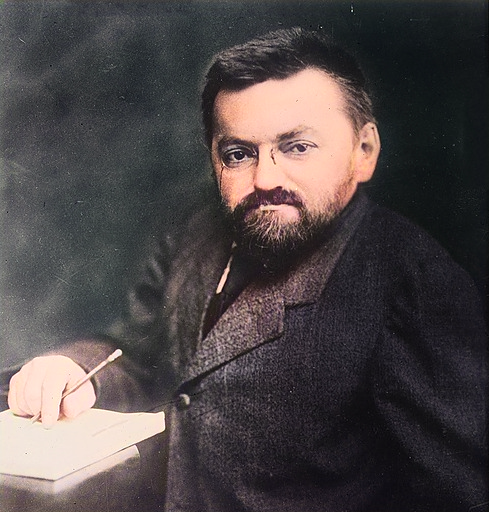

Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865 – 1923)

On October 26, 1923, German-born American mathematician and electrical engineer Charles Proteus Steinmetz passed away. Steinmetz fostered the development of alternating current that made possible the expansion of the electric power industry in the United States, formulating mathematical theories for engineers. He made ground-breaking discoveries in the understanding of hysteresis that enabled engineers to design better electromagnetic apparatus equipment including especially electric motors for use in industry.

“The scientist is contented if he can contribute something toward the knowledge of what is and how it is.”

— Charles P. Steinmetz, New York Times interview (1911)

Education and Emigration to the U.S.

Charles Proteus Steinmetz attended the University of Breslau studying mathematics and chemistry and earned his doctorate degree in 1888. Meanwhile Steinmetz was investigated by the police for his engagement in a socialist university organisation and his articles published in a local socialist newspaper. He fled to Zurich in the same year and managed to escape a possible arrest. One year later he emigrated to the United States and was almost turned away for his dwarfism. However, a friend convinced the American officials that Steinmetz was a brilliant German scientist who could highly benefit American research programes and thus, he was able to move to the United States.

Becoming an Engineering Wizard

Steinmetz began working together with Rudolf Eickemeyer in Yonkers, New York. There, he started publishing in the field of magnetic hysteresis. Eickemeyer then owned a company that developed transformers for use in the transmission of electrical power among other mechanical and electrical devices. In 1893, the Eickemeyer company was taken over by the then newly founded company General Electric. Further work by Steinmetz concerned arc lamps, which he systematically investigated in their operating behaviour and used as floodlight for artificial illumination of large areas.

Back then, Thomas Edison and General Electric became aware of Steinmetz‘s work and began to acquire his patents and services. The Ford company also heard of Steinmetz‘s achievements and they called in the engineer because they had a problem with their giant generator. It is believed that Steinmetz listened to the generator all night, sketching computations on a notepad. Then, he climbed up the generator and proceeded to make chalk marks on its side. He then asked Ford‘s workers to replace sixteen windings from the field coil which solved the problem. The bill presented to Henry Ford however wasn’t a joke, since Steinmetz asked for 10.000$. When Ford asked for an itemized bill, Steinmetz responded: “Making chalk mark on generator: $1. Knowing where to make mark: $9,999“. [1]

“Scientific theories need reconstruction every now and then. If they didn’t need reconstruction they would be facts, not theories.”

— Charles P. Steinmetz, New York Times interview (1911)

Contributions to AC Circuit Theory

Steinmetz‘s contributions to the field highly influenced AC circuit theory and analysis. It became less complicated and less time-consuming. Probably one of his most important publications in the field was Complex Quantities and Their Use in Electrical Engineering. Steinmetz presented his work in July 1893 and it was published in the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. In it, he managed to simplify these complicated calculus-based methods to “a simple problem of algebra“. He systematized the use of complex number phasor representation in electrical engineering education texts, whereby the lower-case letter “j” is used to designate the 90-degree rotation operator in AC system analysis. His seminal books and many other AIEE papers “taught a whole generation of engineers how to deal with AC phenomena“.

Steinmetz was active in Schenectady, where he lived, also in the city administration. From 1901 to 1902 he was president of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE), from 1913 to 1923 first vice president of the International Association of Municipal Electricians (IAME), a predecessor of the International Municipal Signal Association (IMSA). He wrote 13 books, about 60 articles, held 200 patents and was an honorary member of the Phi Gamma Delta student fraternity.

Charles P. Steinmetz died on 26 October 1923 in Schenectady and was buried in Vale Cemetery.

Charles Proteus Steinmetz: The Man Who Made Lightning, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Charles Proteus Steinmetz, the Wizard of Schenectady. Gilbert King. Smithsonian.com

- [2] Charles Proteus Steinmetz at Britannica Online

- [3] Charles Proteus Steinmetz at Tesla Research

- [4] Charles Proteus Steinmetz at the Edison Tech Center

- [5] Charles Proteus Steinmetz at Wikidata

- [6] Charles P. Steinmetz at Reasonator

- [7] Charles Proteus Steinmetz: The Man Who Made Lightning, miSci – museum of innovation and science @ youtube

- [8] Hammond, John Winthrop (1924). Charles Proteus Steinmetz: A Biography. New York: The Century & Co.

- [9] Garlin, Sender (1977). “Charles Steinmetz: Scientist and Socialist (1865–1923): Including the Complete Steinmetz-Lenin Correspondence”. Three Radicals. New York: American Institute for Marxist Studies.

- [10] Lavine, Sigmund A. (1955). Steinmetz, Maker of Lightning. Dodd, Mead & Co.

- [11] Timeline of American Inventors, via Wikidata and DBpedia