Athanasius Kircher (ca. 1602 – 1680)

On May 2nd, 1601 (or 1602), German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher was born. He has published most notably in the fields of oriental studies, geology, and medicine, and has been compared to Leonardo da Vinci for his enormous range of interests.[5] He is regarded as one of the founders of Egyptology for his (mostly fruitless) efforts in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, wrote an encyclopedia about China, studied volcanos and fossils, was one of the very first to observe microbes thorough a microscope, and experimented with the laterna magica as a predecessor of photography.

“Whoever has the desire to pursue philosophy correctly should look to Nature’s Archetype in every matter, so that by taking up Ariadne’s thread in her intricate labyrinth he may keep himself safe and secure from wrong turns and deviant paths.”

— Athanasius Kircher

Youth and Education

Kircher was born on 2 May 1602 in Geisa, a town in the northern Rhön mountains region that belonged to the Fulda high monastery. From 1614 to 1618 he visited the Jesuit College in Fulda. On October 2, 1618 he joined the Jesuit order in Paderborn. He studied philosophy and theology at Academia Theodoriana, but in 1622 he had to flee adventurously to Cologne in order to escape the invading Protestant troops under Duke Christian of Braunschweig-Lüneburg. On his journey he narrowly escaped death after breaking into the ice while crossing the frozen Rhine. Later he worked as a teacher in Heiligenstadt and taught mathematics, Hebrew and Syrian. In 1628 he became a priest and in the same year professor of mathematics and ethics at the University of Würzburg.

Ars Magnesia

In 1631 he published his first book (Ars Magnesia). In the same year, the Thirty Years’ War forced him to continue his work at the Pontifical University of Avignon in France. In 1633 Ferdinand II, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, appointed him to succeed Johannes Kepler as a mathematician at the Habsburg Court in Vienna. However, this appeal was revoked at the instigation of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. Instead, he made a vocation to Rome to the Collegium Romanum, where his friend Kircher would have more time for his research, including work on deciphering the hieroglyphics.

Kircher’s Interest in Egyptology

Kircher’s works were noticed and admired world wide. At the age of almost 30, he began gaining his interest for Egyptology after coming across a collection of hieroglyphs at the library of Speyer. Fascinated by these writings, he studied the Coptic language and published the first Coptic grammar book in 1636. He also explained the relationship between Coptic and other languages in later works. ‘Oedipus Aegyptiacus‘ probably depicts Kircher’s most famous and most successful work, published in the 1650’s. It contains numerous artistic illustrations and interpretations of hieroglyphic texts. Even though Kircher stayed rather unsuccessful, completely understanding the Egyptian hieroglyphs, his work was very influential and highly appreciated by contemporary scientists, such as Sir Thomas Browne. Kircher was one of the first to believe in the phonetic importance of Egyptian hieroglyphs, showing that Coptic was a development of the early Egyptian language, making him one of the founders of Egyptology.

From Noah’s Family to Sinology

Another major field of Kircher’s interests was sinology. His encyclopedia of the Chinese Empire contained detailed cartography combined with mystic symbols and pictures controversially emphasizing certain Christian aspects in the Chinese history. However, he also wrote that the Chinese were descendants of Ham and that the Chinese characters were hieroglyphics modified for Asia, as he had already announced in Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652-1654). To prove this thesis, Kircher constructed an extensive history of colonization of the world by Noah’s family based on biblical narratives.

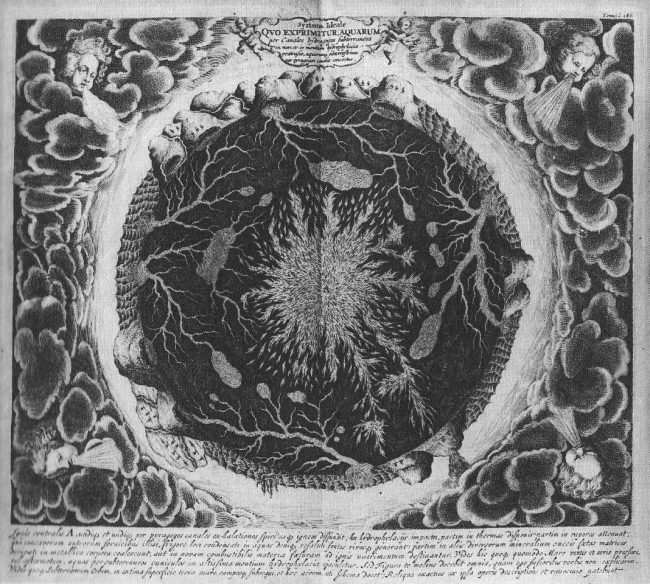

Kircher’s Model of the Earth’s Interior from Mundus subterraneus (1678)

Geological Studies

In the 1630’s, Anthanasius Kircher climbed into Mount Vesuvius‘ crater for research, which inspired him to later publish ‘Mundus Subterraneus‘ (1678). The work contained geological and geographical observations and explanations, assuming that the tides were caused by an underground ocean. Also, he made several hypotheses on fossils and on the structure of Earth’ center. Kircher’s position on fossils was not consistent. He understood that some of these fossils were remains of animals, but he attributed others to the human inventive spirit or spontaneous regenerative forces of the earth. Not all the objects he tried to explain were actually fossils – hence the diversity of his approaches.

The Plagues and Microorganisms

To the most significant contributions Kircher’s in medicine belongs his research on the Plague. Even before 1646, he used a microscope to examine the blood of plague patients. In his work Scrutinium Pestis of 1658, he noticed the presence of “small worms” in the blood and concluded that the disease was caused by microorganisms. The conclusion was correct, although it is likely that what he saw was in fact red or white blood cells. He also proposed hygienic measures such as isolation, quarantine, burning the clothes of the sick and wearing face masks to prevent the spread of the plague.

Title page, Romani Collegii Societatus Jesu musaeum Celeberrimum.

Laterna Magica and Cryptography

Next to the many of Kircher’s scientific contributions to society, he invented several machines, one laterna magica being a very early predecessor of the movie projector and another being the attempt of building a perpetual motion object. Other machines designed or constructed by Kircher were a lead pipeline, a wind harp, a statue that could speak and hear through a mouthpiece. At the same time, he developed a system of encrypted message transmission called stenographia (“secret writing with light”) or cryptologia. In contrast to the optical telegraphy of antiquity, this system used a concave mirror which is labeled with the characters to be transmitted. With this procedure, military commands could be transmitted over a distance of about three and a half kilometres “tap-proof”. He often related to theological topics scientifically. For instance he tried to comprehend the technical standard of Noah’s Arc based on the studies of the mathematician Johannes Buteo.

Music Theory

In Musurgia Universalis (1650) with numerous sheet music examples from contemporary music, Kircher presents his views on music and the theory of affects. He believed that the harmony of music reflected the proportions of the universe. Organ building is treated in particular detail. In this book Kircher describes plans of hydro-powered automatic organs, the characteristics of bird song and the construction of musical instruments. In Polygraphia nova (1663) Kircher proposes an artificial universal planning language created by him. Kircher took a critical stance towards the possibility of transmutation of metals asserted in alchemy. He did not completely rule this out, but said that this was only possible with dark powers or feigned by diabolical deception, which led to critical confrontations with supporters of this direction of alchemy. In Phonurgia Nova (1673) Kircher considered the possibilities of transmitting music to remote places.

The first Scholar with a Worldwide Reputation

During much of his scientific career, Kircher was considered one of the most popular scholars of the world at that time. According to the American historian Paula Findlen, Kircher was “the first scholar with a worldwide reputation”. He achieved his importance with a double strategy: to his own researches and experiments he added the information he gathered from his correspondence with over 760 other scientists, physicists and above all his Jesuit brothers from all over the world. From today’s perspective, his works appear as a mixture of the results of genuine research, thoughtful relationship management, forward-looking intuition, mere speculation, and admirable marketing. After his death in 1680, Kircher’s work was largely punished with disrespect until the late 20th century. From then on, however, it experienced a certain renaissance. Umberto Eco wrote about Kircher both in his novel The Island of the Day before and in his non-fictional texts The Search for Perfect Language and Serendipities. Language and Lunacy.[6]

Mariana Francozo, Talk 6: “Searching for Athanasius Kircher’s Brazilian collection”, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Sic ludit in orbe terrarum aeterna Dei sapientia” – Harmonie als Utopie : Untersuchungen zur Musurgia universalis von Athanasius Kircher / vorgelegt von Melanie Wald [PDF], in German

- [2] Erkenntnisse – Phantasien – Visionen. Athanasius Kirchers geologisches Weltbild im Lichte heutiger Anschauungen, in German

- [3] The Life of Athanasius Kircher

- [4] Athanasius Kircher at Stanford

- [5] Leonardo Da Vinci – the Prototype of a Renaissance Man, SciHi Blog

- [6] Umberto Eco and The Name of the Rose, SciHi Blog

- [7] Athanasius Kircher at Wikidata

- [8] Works by or about Athanasius Kircher at Wikisource

- [9] Athanasius Kircher, Ars magna lucis et umbrae in decem libros digesta (1646) in the digital collections of the Linda Hall Library

- [10] Mariana Francozo, Talk 6: “Searching for Athanasius Kircher’s Brazilian collection”, [10]

- [11] Timeline of Jesuit scientists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Yes it’s true, there’s an interesting relationship between Kircher and Browne, so much so that Browne stated of Kircher’s Egyptology, in ‘Pseudodoxia Epidemica’,

‘But no man is likely to profound the Ocean of that Doctrine, beyond that eminent example of industrious Learning, Kircherus’. (P.E. Bk 1 ch. 9)

He was probably one of Sir T.B.’s favourite reads, these books by Kircher are listed as once in Browne’s library.

Ars Magnesia 1631

Ars Magna Lucis & Umbrae, cum fig. Rome 1646

Obeliscus Pamphilus, cum fig. Rome 1650

Oedipus Egypticus 3 tomi cum fig Rome 1650-56

Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica, cum fig Rome 1654

Iter Ecstaticum Kirceranium, ed. G. Schott 1660

Mundus Subterraneous, cum fig 2 vol. Amsterdam 1665

China Illustrata cum fig. Amsterdam 1667

Thank you for the friendly comment and the additional information 🙂

now you share the mind in the knowledge point .. now you can share the knowledge any topics about every things what you about..

knowledge sharing

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #38 | Whewell's Ghost

Typo: Kircher was one of the fist to believe in the phonetic importance of Egyptian hieroglyphs . . .

Thanks a lot for realizing and telling us! It’s already corrected.