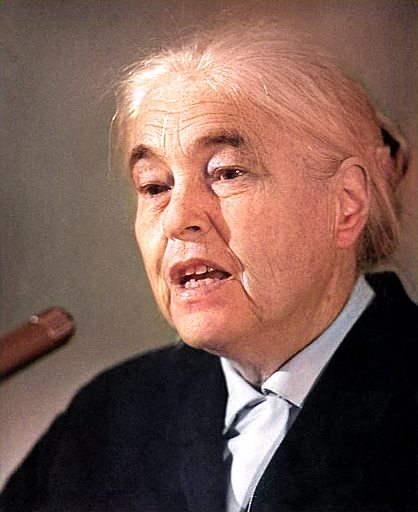

Anna Seghers (19 November 1900 – 1 June 1983), Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-F0114-0204-003 / Hochneder, Christa / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

On November 19, 1900, German writer Anna Seghers was born. Seghers became famous for depicting the moral experience of the Second World War. I came across the writer at the end high school. “The Seventh Cross” of Anna Seghers was the last piece of literature that we officially had to read in the German literature courses before high school graduation. And I remember that I was rather impressed by this novel.

“What can I expect here? You know the fairy tale about the man who died, don’t you? He was waiting in Eternity to find out what the Lord had decided to do with him. He waited and waited, for one year, ten years, a hundred years. He begged and pleaded for a decision. Finally he couldn’t bear the waiting any longer. Then they said to him: ‘What do you think you’re waiting for? You’ve been in Hell for a long time already.”

― Anna Seghers, Transit

Family Background and Education

Anna Seghers was born as Netty Reiling, the only child of the Mainz art and antiques dealer Isidor Reiling and his wife Hedwig (née Fuld). Her father was a member and a proportionate developer of the Jewish New Orthodox Synagogue in Mainz. From 1907, Netty attended a private school, then from 1910 the Higher Girls’ School in Mainz. During the First World War she served as auxiliary assistance. She graduated from high school in 1920, and then studied history, art history and sinology in Cologne and Heidelberg. In 1924 she received her doctorate from the University of Heidelberg with a dissertation on Jewry and Judaism in Rembrandt‘s work.

Becoming Anna Seghers

In 1925 she married László Radványi, a Hungarian sociologist from a Jewish family, who later called himself Johann Lorenz Schmidt. The couple moved to Berlin, where they lived from 1925 to 1933 in the Wilmersdorf district. In the 1924 Christmas supplement of the Frankfurter Zeitung, she was able to publish her first short story Die Toten auf der Insel Djal under the pen name Antje Seghers. She borrowed the pseudonym from the Dutch etcher and painter Hercules Seghers (the name was also written Segers).

In 1928 her daughter Ruth was born and her first book Aufstand der Fischer von St. Barbara (Revolt of the Fishermen of Santa Barbara) was published under the pseudonym Anna Seghers. In the same year she was awarded the Kleist Prize for her first work at the suggestion of Hans Henny Jahnn. She also joined the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1928 and in the following year she was a founding member of the Bund proletarisch-revolutionärer Schriftsteller (League of Proletarian Revolutionary Writers). In 1930 she travelled to the Soviet Union for the first time.

Flight Into Exile

After the National Socialists seized power, Anna Seghers was briefly arrested by the Gestapo; her books were banned and burned in Germany. Shortly afterwards she was able to flee to Switzerland, from where she went to Paris. In exile, she worked on magazines for German emigrants, including as a member of the editorial staff of Neue Deutsche Blätter. In 1935 she was one of the founders of the Schutzverband Deutscher Schriftsteller (Protection Association of German Writers) in Paris. After the beginning of the Second World War and the invasion of Paris by German troops, Seghers’ husband was interned in the camp Le Vernet in southern France. Anna Seghers and her children managed to escape from occupied Paris to the part of southern France ruled by Henri Philippe Pétain. There, in Marseille, she tried to secure the release of her husband and to find ways to leave the country. Her efforts were finally successful at the Mexican Consulate General led by Gilberto Bosques, where refugees were issued generous entry permits. This period formed the background to the novel Transit (published in 1944).

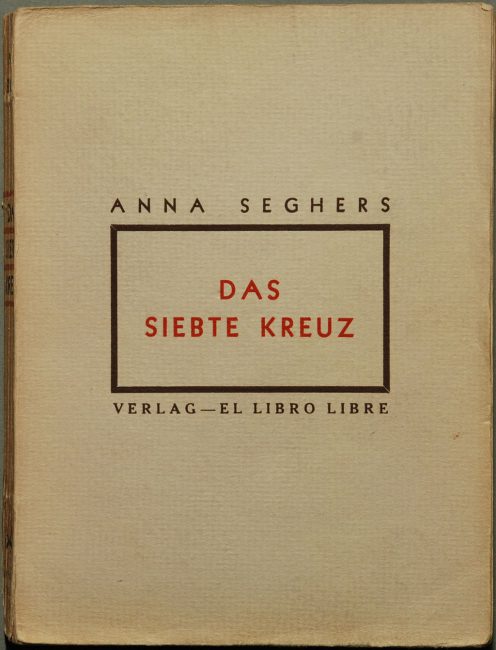

Cover of Anna Seghers’ “The Seventh Cross”, photo: H.-P.Haack

The Seventh Cross

In March 1941 Anna Seghers managed to emigrate with her family from Marseille via Martinique, New York, Veracruz to Mexico City. Her husband, who in the meantime called himself Johann Lorenz Schmidt, found employment there, first at the Workers’ University and later at the National University. Anna Seghers founded the anti-fascist Heinrich Heine Club, of which she became president. Together with Ludwig Renn, she founded the Free Germany Movement and published its magazine of the same name. In 1942 her novel Das siebte Kreuz (The Seventh Cross) was published in an English edition in the USA and in German in Mexico. The novel telly the story of the flight of seven prisoners from a concentration camp during the National Socialist era. In seven chapters, the novel describes the protaginist’s seven-day escape, which could only succeed because Heisler, despite all his courage, is not an individualist like the other fugitives, but as a communist finds support among his comrades in the underground. But also good-hearted Germans, not politically organized, help him on his escape.

“What magic was this, brewed from equal parts of age-old memories and total oblivion. One could have believed that the last war these people had fought had left only happy memories, had carried in its wake nothing but joy and prosperity. Women and girls were smiling as if their sons and lovers were invulnerable.”

― Anna Seghers, The Seventh Cross

Return to Germany and Later Years

In June 1943 Anna Seghers suffered serious injuries in a traffic accident, which made a long stay in hospital necessary. In 1944 Fred Zinnemann [7] filmed Das siebte Kreuz (The Seventh Cross) – the success of book and film made Anna Seghers world famous. In 1947 Seghers left Mexico and returned to Berlin, where she initially lived in West Berlin as a member of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany. At the First German Writers’ Congress in October 1947, she gave a much-noticed speech on exile and the concept of freedom. That year she was awarded the Georg Büchner Prize. In 1950 she moved to East Berlin and was appointed a member of the World Peace Council and a founding member of the German Academy of Arts. In 1951 she was awarded the GDR National Prize and made a trip to the People’s Republic of China. In 1952 she became president of the writers’ association of the GDR and remained so until 1978.

In 1975 she was awarded the Culture Prize of the World Peace Council and honorary citizenship of (East) Berlin. In 1978 she resigned as President of the Writers’ Association and became its Honorary President. Her husband died in the same year. In 1979, Anna Seghers remained silent about the expulsion of nine critical authors from the Writers’ Association. In 1981 she was awarded honorary citizenship of her native city of Mainz. She died on 1 June 1983, at age 82.

Anna Seghers’ Work and Legacy

The early works of Anna Segher can be classified as New Objectivity. In exile literature she not only played an important role as an organizer, but also wrote two of the most literarily significant novels of her time, Transit and The Seventh Cross. Her later novels, published in the GDR, are committed to Socialist Realism. They show a schematic figure guidance and irritate by their party loyalty, which can be traced back not least to the numerous official functions. In contrast to the novels of the fifties and sixties, the late stories retain their literary validity. Seghers proved her narrative freshness until old age, not least because she repeatedly picked up material from the Renaissance, East Asia, the Caribbean or Mexico, which she was able to tell with sensitivity and knowledge, as well as with great inventiveness and creative talent – beyond all clichés – in a literary great way.

The Seventh Cross (trailer) – Anna Seghers – Fred Zinnemann – Spencer Tracy, [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Die-Anna-Seghers-Home-Page (in German)

- [2] Anna Seghers biography by Ian Wallace

- [3] The Seventh Cross, at IMDB

- [4] Anna Seghers at Wikidata

- [5] The Seventh Cross (trailer) – Anna Seghers – Fred Zinnemann – Spencer Tracy, Constantart @ youtube

- [6] Heinrich Mann – Social Criticism, Marlene Dietrich, and Californian Exile, SciHi Blog

- [7] Fred Zinnemann – From High Noon to The Day of the Jackal, SciHi Blog

- [8] Sonja Hilzinger: Seghers, Anna. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, S. 162–164

- [9] Timeline for Anna Seghers, via Wikidata