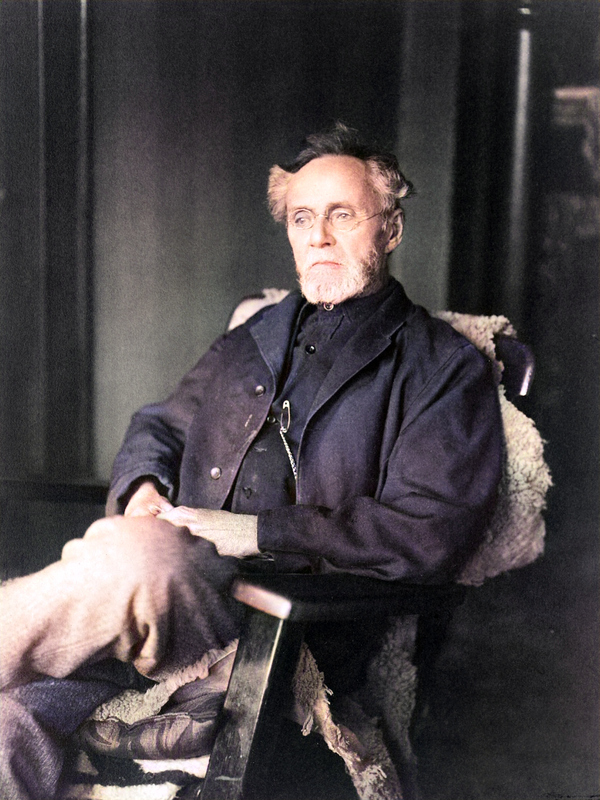

Andrew Taylor Still (1828-1917)

On August 6, 1828, American surgeon and physician Andrew Taylor Still was born. Still was the founder of osteopathy and osteopathic medicine, a type of health care system of diagnosis and treatment that emphasizes relationship between structure and function in the body, and the ways it can be affected through manipulative therapy and other treatment modalities.

“An osteopath is only a human engineer, who should understand all the laws governing his engine and thereby master disease.”

– Autobiography of A.T. Still, page 253.

Andrew Taylor-Still – Early Years

Still was born in Lee County, Virginia, to the Reverend Abram Still, a Methodist minister and physician and Martha Moore Still. After the Still family moved to Bloomington in Macon County, Missouri, in 1837, Andrew’s education was sporadic and split between attending school and being taught by his parents.[3] Already at an early age, Still decided to follow in his father’s footsteps as a physician. After studying medicine and serving an apprenticeship under his father, Still became a licensed MD in the state of Missouri [1]. He entered the Civil War in 1861 as a hospital steward until he was discharged in 1862. In early 1864 two of Still’s own children, as well as a child he had adopted, died from meningitis. A fourth child died of pneumonia.[3]

Problems with Orthodox Medical Practices

Still concluded that the orthodox medical practices of his day were frequently ineffective and sometimes harmful. Unfortunately, doctors did not know that the medicines they used were toxic because pharmacology was not very advanced.[3] After the war ended, Still returned home but was unable to farm due to a hernia he suffered during the Civil War battle of Westport, Missouri. Despite his doubts about traditional medicine, he worked as a physician to provide for his family. He devoted the next thirty years of his life to studying the human body and finding alternative ways to treat disease. During this period, he completed a short course in medicine at the new College of Physicians and Surgeons in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1870.

The Birth of Osteopathy

Still adopted the ideas of spiritualism sometime around 1867, and it held a prominent and lasting place in his thinking. Still sought to reform existing 19th-century medical practices and investigated alternative treatments, such as hydropathy, diet, bonesetting, and magnetic healing. He found appeal in the relatively tame side effects of those modalities, and imagined that someday “rational medical therapy” would consist of manipulation of the musculoskeletal system, surgery and very sparing use of drugs, including anesthetics, antiseptics and antidotes. He came to believe that a properly aligned musculoskeletal system would lead to good health, while an out-of-alignment system would result in poor health. Bones, muscles, and joints could be manipulated and adjusted by a physician to improve a patient’s health without the use of drugs. He called his theory of medicine “osteopathy,” blending two Greek roots osteon- for bone and -pathos for suffering in order to communicate his theory that disease and physiologic dysfunction were etiologically grounded in a disordered musculoskeletal system. Thus, by diagnosing and treating the musculoskeletal system, he believed that physicians could treat a variety of diseases and spare patients the negative side-effects of drugs.

Branches of Osteopathy

Still founded the first school of osteopathy based on this new approach to medicine – the school was called the American School of Osteopathy (now A.T. Still University) in Kirksville, Missouri in 1892. Still suffered a severe stroke in 1914 and lost his ability to speak. Andrew Taylor Still died on December 12, 1917. The osteopathic profession has evolved into two branches, non-physician manual medicine osteopaths and full scope of medical practice osteopathic physicians. These groups are so distinct that in practice they function as separate professions. The regulation of non-physician manual medicine osteopaths varies greatly between jurisdictions. Osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM), also known as osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), is a core set of techniques of osteopathy and osteopathic medicine distinguishing these fields from mainstream medicine. Still had posited the existence of a myofascial continuity – a tissue layer that connects all parts of the body. Non-physician osteopaths and osteopathic physicians attempt to diagnose and treat somatic dysfunction by manipulating a person’s bones and muscles and therefore address a variety of ailments. OMT techniques are most commonly used to treat back pain and other musculoskeletal issues, and are less commonly used to treat systemic conditions such as asthma and Parkinson’s disease.[7]

A Strong Dose of Healthy Living

Still’s proposed treatment regime also included as strong dose of healthy living: he advocated abstinence from alcohol, and patients were forbidden from taking medicine. However, the effectiveness of osteopathy is not conclusive and therefore it is not commonly acknowledged as part of mainstream medicine and criticized as being a “pseudoscientific practice“, which “will and should follow homeopathy, magnetic healing, chiropractic, and other outdated practices into the pages of medical history“.[6]

In 2014, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials found moderate-quality evidence that OMT reduces pain and improves functional status in acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain.[4] The same analysis also found moderate-quality evidence for pain reduction for nonspecific low back pain in postpartum women and low-quality evidence for pain reduction in nonspecific low back pain in pregnant women.[4] A 2013 systematic review found insufficient evidence to rate osteopathic manipulation for chronic nonspecific low back pain.[5]

Curiosities and Controversies

In his autobiography, he described himself as “possibly the best living anatomist”. Andrew Taylor Still denied the existence of microbes, already firmly established by Louis Pasteur in his time, as well as the role they played in the development of diseases, as demonstrated by Robert Koch. In 1910, he wrote his first textbook for the school he founded. In it he described his methods of manual therapy on the spine, with the help of which he believed to have “cured” yellow fever, malaria, rickets, haemorrhoids, diabetes, dandruff as well as obesity. Still also believed that rubbing the spine of a bald person would reverse hair loss or cause continued hair growth. He believed that diseases were based on malfunctioning nerves and blood supply. These were caused by blocking individual parts of the body (joints, bones, fasciae) and were largely to blame if the body could not cope with healing on its own. It is the task of the osteopath to find and “adjust” these blockages. It is not clear how these “adjustments” will hold by themselves.

Gina Moses, Osteopathic Medicine: Myths and Realities, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] A Brief History of Osteopathic Medicine

- [2] Andrew Taylor Still MD, at osteodoc

- [3] A. T. Still (1828 – 1917), at Historic Missourians

- [4] Franke H, Franke JD, Fryer G (August 2014). “Osteopathic manipulative treatment for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. BMC Musculoskelet Disord (Systematic review & meta-analysis) 15 (1): 286.

- [5] Orrock PJ, Myers SP (2013). “Osteopathic intervention in chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review”. BMC Musculoskelet Disord (Systematic review) 14: 129.

- [6] Bryan E. Bledsoe (2004). “The Elephant in the Room: Does OMT Have Proved Benefit?”. J Am Osteopath Assoc (Letter) 104 (10): 407.

- [7] James Parkinson and Parkinson’s Disease, SciHi Blog

- [8] Andrew Taylor Still at Wikidata

- [9] Gina Moses, Osteopathic Medicine: Myths and Realities, 2015, UC Berkeley Events @ youtube

- [10] “Andrew Taylor Still: The Father of Osteopathic Medicine”. A.T. Still University Museum.

- [11] Trowbridge, Carol (2007). Andrew Taylor Still, 1828-1917. Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press.

- [12] Timeline of 19th century American Physicians, via Wikidata and DBpedia