The James Lick Telescope, photo: myyorgda, (CC BY 2.0)

On January 3, 1888, the James Lick Telescope saw first light at the Lick observatory, San Jose, USA. The Lick telescope is a refracting telescope with a lens 91 cm in diameter – a major achievement in its day and in its time the largest telescope in the world until 1897. The instrument remains in operation and public viewing is allowed on a limited basis. A lot of astronomical discoveries have been made with the Lick telescope.

The Lick Trust

In 1821 James Lick set up in the pianoforte business at New York, and later was a manufacturer of musical instruments at Buenos Aires, Philadelphia, Valparaiso and elsewhere. In 1847 he went to California, where he gained wealth through investments in real estate and various enterprises. In 1874 he placed $3,000,000 at the disposal of seven trustees, by whom they were to be applied to specific uses. Among other bequests, the University of California should receive $700,000 for the construction of an observatory and the placing therein of a telescope to be more powerful than any other in existence.[1,7] Richard Floyd, president of the Lick Trust, together with famous American astronomer Simon Newcomb of the U.S. Naval Observatory as scientific advisor had to make a design decision for the new telescope: refractor or reflector?

James Lick (1796 – 1876)

Refractor or Reflector?

Refractors employ lenses to focus light. They had been the choice of most astronomers since the invention of the telescope. But, reflectors, which use mirrors instead of lenses, were gaining acceptance as mirror making materials and techniques improved and the reflector’s optical advantages became evident. However, the board of trust decided to follow a more conservative approach and to construct a refractor, but of gigantic dimensions.

Warner & Swasey designed and built the telescope. The fabrication of the two-element 91-centimeter achromatic objective lens, the largest lens ever made at the time, caused years of delay. The famous large telescope maker Alvan Clark was in charge of the optical design. He gave the contract for casting the high quality optical glass blanks, of a size never before attempted, to the firm of Charles Feil in Paris, France. Transportation of these large and fragile glass lenses was a considerable challenge in the 1800s. The glass disks came from France to Boston by ship. One of the huge glass disks broke during shipping, and making a replacement was delayed. Finally, after 18 failed attempts, the lens was finished and safely crossed the continent on a specially designed railroad car, making the last leg of the journey by horse and wagon, arriving safely on the summit two days after Christmas, 1886. On December 31, 1887, the large lens was carefully installed in the telescope tube.

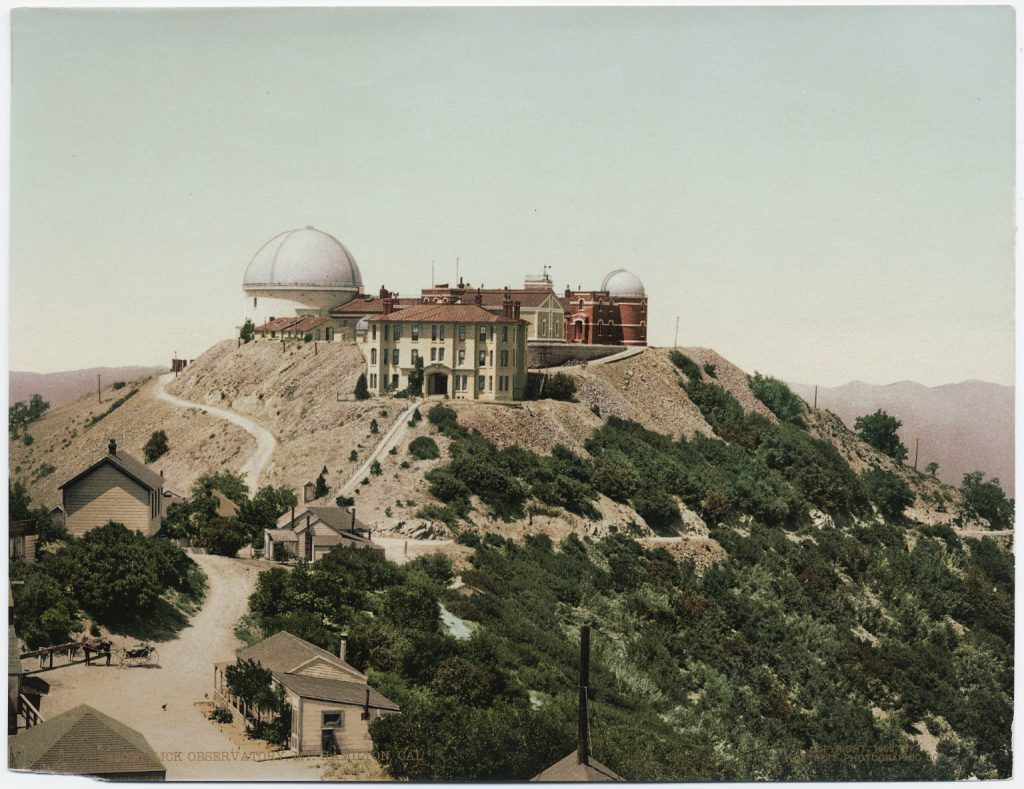

The Lick Observatory on Mt Hamilton, a photochrom postcard published by the Detroit Photographic Company. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University (1897-1924)

At the Summit of Mt Hamilton

Lick had directed to construct his observatory at a place on top of Mt. Hamilton in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California. Lick additionally requested that Santa Clara County construct a “first-class road” to the summit, completed in 1876. All of the construction materials had to be brought to the site by horse and mule-drawn wagons, which could not negotiate a steep grade. To keep the grade below 6.5%, the road had to take a very winding and sinuous path, which the modern-day road still follows. The plan for the observatory’s main building called for two domes, the larger of which would house the Great Refractor, connected by a long hallway flanked by offices, laboratories, and a library. According to his last will, in January 1887, James Lick was brought, for the first time, to the summit of Mt. Hamilton, and laid to rest, for the last time, at the base of the pier, hidden from sight beneath the floor of his great telescope.

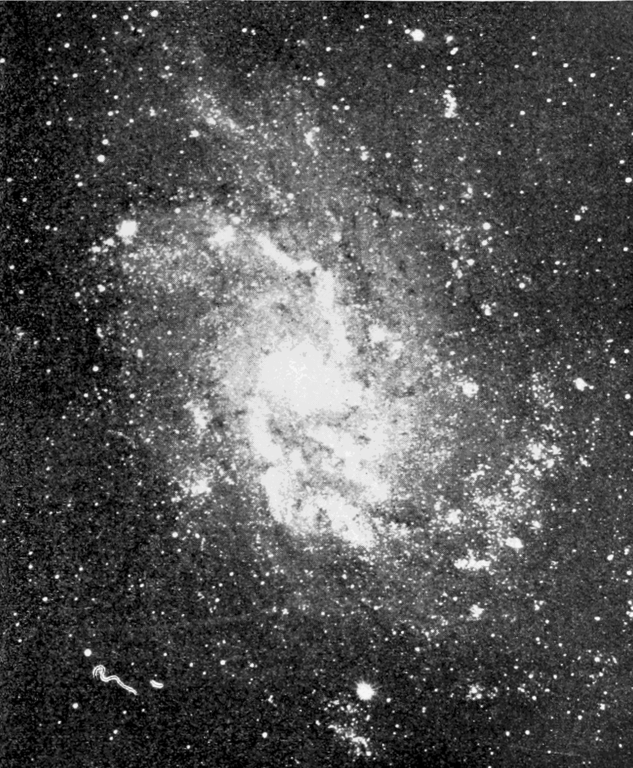

Spiral nebula M 33 by the Lick observatory 1900

First Light

After the lens had been installed in the telescope tube, the builders had to wait for three days for a break in the clouds to test it. On the evening of January 3 the telescope saw “first light” — and they found that the instrument couldn’t be focused. An error in the estimation of the lens’ focal length had caused the tube to be built too long. A hacksaw was procured, the great tube was unceremoniously cut back to the proper length and the star Aldebaran in the zodiac constellation of Taurus came into focus.

In May 1888, the observatory was turned over to the Regents of the University of California, and it became the first permanently occupied mountain-top observatory in the world. The location provided excellent viewing performance because of lack of ambient light and pollution; additionally, the night air at the top of Mt. Hamilton is extremely calm, and the mountain peak is normally above the level of the low cloud cover that is often seen in the San Jose area.

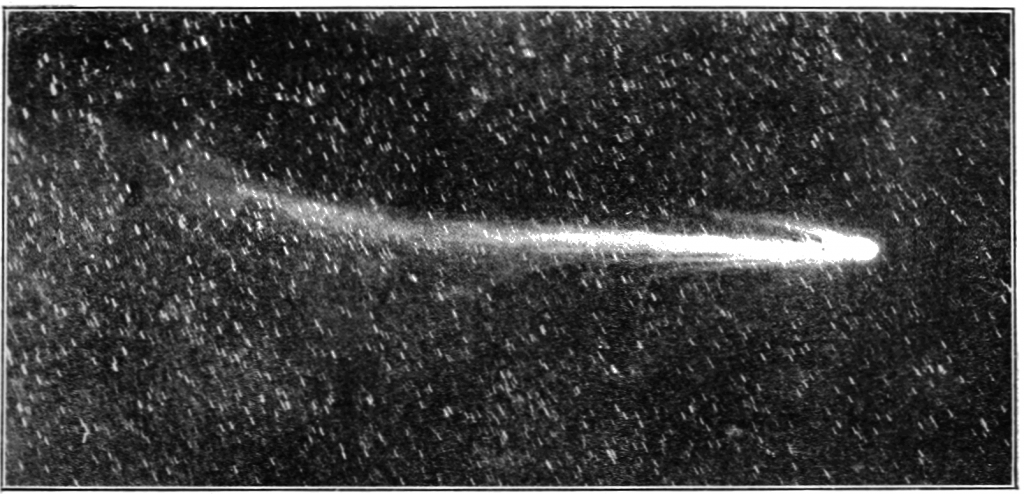

Comet morehouse photographed at the lick observatory nov 15 1908

Important Discoveries

E. E. Barnard used the telescope in 1892 to discover a fifth moon of Jupiter, Amalthea. This was the first addition to Jupiter’s known moons since Galileo observed the planet through his parchment tube and spectacle lens. Jupiter is now known to have at least 50 true moons. The telescope provided spectra for W. W. Campbell’s work on the radial velocities of stars. Although primarily of historical interest, the Lick Refractor is still used infrequently for research. Currently it is used to observe the separation and orbits of binary stars. It is often used as a teaching telescope for university and college astronomy classes as well as for NASA teachers workshops.[3]

Hercules cluster photo from the lick observatory, Popular Science Monthly Volume 58 (1900/01)

Light Pollution

With the growth of San Jose, and the rest of Silicon Valley, light pollution became a problem for the observatory. In the 1970s, a site in the Santa Lucia Mountains at Junípero Serra Peak, southeast of Monterey, was evaluated for possible relocation of many of the telescopes. However, funding for the move was not available, and in 1980 San Jose began a program to reduce the effects of lighting, most notably replacing all streetlamps with low pressure sodium lamps. The result is that the Mount Hamilton site remains a viable location for a major working observatory.

Lick Observatory: Over 100 Years of Discovery, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Building the Observatory, at The Lick Observatory website

- [2] Photographs of the James Lick telescope from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library’s Digital Collections

- [3] The Great Lick Refractor, at Telescopes at the Lick Observatory

- [4] The Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory, SciHi Blog, January 26, 2014.

- [5] “Lick Observatory Edition”. Mining and Scientific Press. June 23, 1888.

- [6] The Encyclopedia Americana (1920)/Lick Observatory, at Wikisource

- [7] Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- [8] Lick Observatory at Wikidata

- [9] Lick Observatory: Over 100 Years of Discovery, University of California Television (UCTV) @ youtube

- [10] Timeline for telescopes, according to Wikidata (cf below)