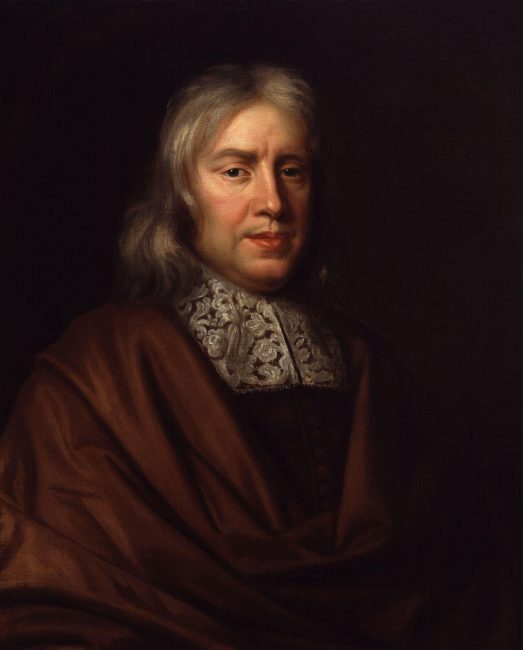

Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689)

On September 10, 1624, English physician Thomas Sydenham was born. He was the author of Observationes Medicae which became a standard textbook of medicine for two centuries so that he became known as ‘The English Hippocrates’. Among his many achievements was the discovery of a disease, Sydenham’s Chorea, also known as St Vitus Dance.

Thomas Sydenham’s struggles with the medical degree

Thomas Sydenham was born at Wynford Eagle in Dorset, the son of William Sydenham, a Dorset squire who became a close confidant of Cromwell and a prominent figure during the Commonwealth. In 1642 Sydenham was entered at Magdalen Hall, Oxford; after a short period his college studies appear to have been interrupted, and he served for a time as an officer in the Parliamentarian army during the Civil War. He completed his Oxford course in 1648, graduating as bachelor of medicine, and about the same time he was elected a fellow of All Souls College. It was not until nearly thirty years later (1676) that he graduated as M.D., not at Oxford, but at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge,[1] where his eldest son was by then an undergraduate.

“Of all the remedies it has pleased almighty God to give man to relieve his suffering, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium” (Thomas Sydenham)

After 1648 he seems to have spent some time studying medicine at Oxford, but he was soon back in military service, and in 1654 he received the sum of £600, as a result of a petition he addressed to Oliver Cromwell, pointing out the various arrears due to two of his brothers who had been killed and reminding Cromwell that he himself had also faithfully served the parliament with the loss of much blood.

“I confidently affirm that the greater part of those who are supposed to have died of gout, have died of the medicine rather than the disease – a statement in which I am supported by observation.” (Thomas Sydenham)

In 1655 he resigned his fellowship at All Souls, married Mary Gee in his home town of Wynford Eagle. In 1663 he passed the examinations of the College of Physicians for their licence to practice in Westminster and 6 miles round; but it is probable that he had been settled in London for some time before that. He rejected on religious grounds attempts such as pathological anatomy and microscopic analysis to uncover the hidden causes of disease. He argued God only gave man the ability to perceive the outer nature of things with his senses. Sydenham valued methodical observation and practical experience of medicine over a search for causes. He developed the concept of ‘species’ of disease to improve medical diagnosis by describing and classifying different illnesses.[2]

“The art of medicine was to be properly learned only from its practice and its exercise.” (Thomas Sydenham)

He seems to have been distrusted by some members of the faculty because he was an innovator and something of a plain-dealer. He rejected on religious grounds attempts such as pathological anatomy and microscopic analysis to uncover the hidden causes of disease. He argued God only gave man the ability to perceive the outer nature of things with his senses. Sydenham valued methodical observation and practical experience of medicine over a search for causes. He developed the concept of ‘species’ of disease to improve medical diagnosis by describing and classifying different illnesses.[2] Despite his objection to theory and his insistence on a purely empirical medicine, he accepted the traditional concept that diseases resulted from disturbances of the bodily humors. He revived the Hippocratic notion that the seasons and atmospheric conditions played an equally important role, but he differed from Hippocrates in the emphasis he placed on the recognition of specific diseases. He believed that the detailed study of the natural history of any disease would eventually indicate what specific medication should be used for its treatment.[3]

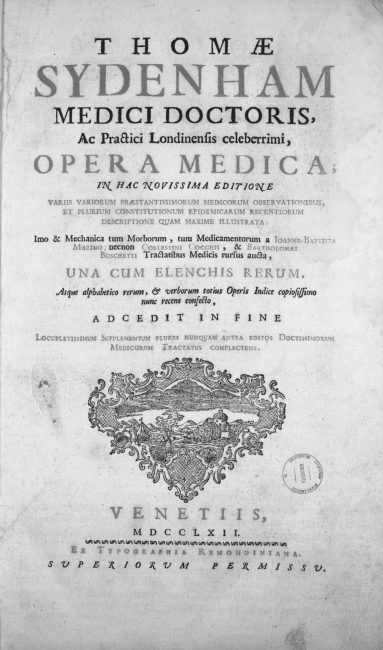

Thomae Sydenham, Opera medica /1762)

Sydenham’s famous publications

Sydenham’s exact study of epidemics formed the basis of his book on fevers (1666), which was dedicated to his friend, the Irish-born chemist and natural philosopher Robert Boyle,[5] later expanded into Observationes Medicae (1676), a standard textbook for two centuries. Sydenham had ample opportunity to study epidemics. He saw the Great Plague of London, followed by severe epidemics of smallpox. Sydenham, however, wisely spent the plague years in the countryside. His Treatise on Gout (1683) is considered his masterpiece.[4] He himself suffered from gout and wrote an excellent description of the disease, detailing the attack, the changes in urine and the link with renal stones. He also presented the theory of an epidemic constitution, ie. conditions in the environment (air, season, etc.) which cause the occurrence of acute diseases. For a long time Sydenham was held in vague esteem for the success of his cooling (or rather expectant) treatment of smallpox, for his laudanum (the first form of a tincture of opium), and for his advocacy of the use of “Peruvian bark” in quartan agues, in modern terms, the use of quinine-containing cinchona bark for treatment of malaria caused by Plasmodium malariae.

Later Years

In his last years, Sydenham was considerably disabled by gout and renal disease and died at his home in Pall Mall in 1689.[1] Syndenham’s associates included Robert Boyle and John Locke.[4,5] Sydenham, Locke, and Boyle had much in common in their approach to acquiring knowledge of the natural world. They held similar views in epistemology and shared an admiration for Bacon. The question of who might have influenced whom has often been debated, since the results of their respective efforts in medicine, philosophy, and chemistry have been so far-reaching.

Hardly anything is known of Sydenham’s personal history in London. He died at his house in Pall Mall on 29 December 1689, aged 65. He is one of 23 original names on the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s frieze listing individuals who have made outstanding contributions to public health and tropical medicine.

Dickson Despommiers, Daniel Griffin, Parasitic Diseases Lectures #12: The Malarias Part One [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Sydenham, Thomas.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 10 Sep. 2015

- [2] Thomas Sydenham at The ScienceMuseum

- [3] Thomas Sydenham at YourDictionary.com

- [4] Thomas Sydenham at Britannica Online

- [4] John Locke and the Social Contract, SciHi Blog

- [5] Robert Boyle – The Sceptical Chemist, SciHi blog

- [6] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Sydenham, Thomas“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–278

- [7] Pearce, J M (March 1995). “Thomas Sydenham “The British Hippocrates““. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 58 (3): 292.

- [8] Stewart, J S (1953). “A claim to fame: Thomas Sydenham”. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 29 (335): 465–7

- [9] Sydenham, Thomas; English edition by Greenhill, William Alexander; Latham, R. G (1848). The works of Thomas Sydenham. (1848). Volume 1. London. Sydenham Society

- [10] Sydenham, Thomas; English edition by Greenhill, William Alexander; Latham, R. G (1848). The works of Thomas Sydenham. (1848). Volume 2. London. Sydenham Society

- [11]Dickson Despommiers, Daniel Griffin, Parasitic Diseases Lectures #12: The Malarias Part One, Parasites without Borders @ youtube

- [12] Thomas Sydenham at Wikidata

- [13] Timeline of 17th century English medical doctors, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #09 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #20 | Whewell's Ghost