The Ideal Picture of Steller’s Sea Cow by Johann Friedrich von Brandt based on the Pallas Picture and skeletons (1868)

On March 10, 1709, German botanist, zoologist, physician and explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller was born. He joined the Russian explorer Vitus Bering on his second expedition to Kamchatka and Alaska, where he discovered numerous new species, as e.g. the Steller‘s sea cow that was named after him.

From Theology to Medicine

Steller was born as Georg Wilhelm Stöller and grew up in Windsheim, near Nuremberg in Germany, son to a Lutheran cantor named Johann Jakob Stöhler. Due to his father being a protestant church organist, Stöller early decided to begin studying theology in Wittenberg, but after some time his interest in medicine and nature science grew so much that he decided to fully dedicate his student life to medicine, graduating at ‘Obercollegium medicum’ at Berlin in 1734.

The Kamchatka Expedition

Shortly after his graduation, Stöller moved to Saint Petersburg connecting with fellow scientists like Johann Ammann at the Academy of Sciences. This is also when, due to problems transcribing his name into cyrillic letters, his name was changed into “Steller.” When finding out about an open position at a recent Kamchatka Expedition he applied, was accepted and left Saint Petersburg in 1737. His journey was interrupted by an unplanned stop of a whole year in Irkutsk, where he documented 1152 plants in his ‘Flora Irkuntiensis manuscript.

Meeting Vitus Bering and the Great Nordic Expedition

The first meeting with Vitus Bering took place in 1740 not far from Ochotsk.[5] Vitus Bering was a well known explorer and officer of the Russian Navy, with an amazing reputation due to his later explorations of the north-eastern coast of the Asian continent and the western coast of the North American continent. However, Georg Wilhelm Steller and his fellow travelers continued their way to the southern island of Kamtschatka studying its nature and civilization. Vitus Bering back then prepared for his trip to America from Kamtschatka, inviting Steller to come along on his Boat called ‘Sankt Peter’, which he gratefully did.

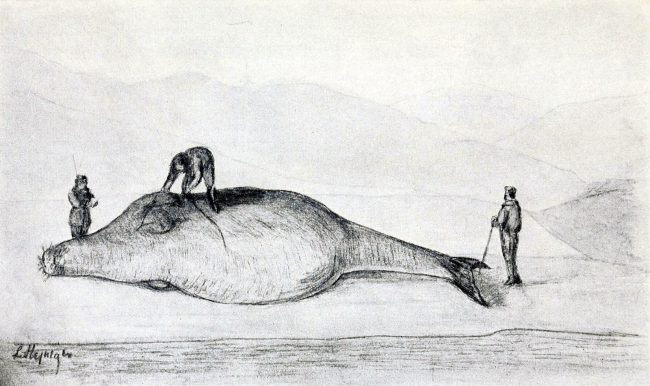

Bering’s Death and the Discovery of the Sea Cow

The explorers’ ship reached Kayak Island near Alaska’s dry land, where Steller was able to document (due to time issues) a rather small catalog of discovered plants. The crew then managed to arrive a piece of land, that is now called Bering Island, where the head of the exploration, Vitus Bering passed away. Since their ship had to be fixed in order to return home, Steller took his time to explore the island resulting in the discovery of the famous and now extinct sea cow, named after Steller. In 1744, Steller began his journey home, passing away in November 1746 in Tyumen.

One of the largest Mammals of the Holocen

Even though, Steller discovered several animals and plants now named after him, the sea cow depicts one of the most famous and most important due to its short lifetime on Earth and its extinction due to over hunting the averagely 8,000 kg marine mammal. Unfortunately, the sea cow was according to Steller a slow swimmer and could not escape the many hunters following the Bering’s route. It was hunted for both, for food and its skin in order to manufacture boats out of them. Steller’s sea cows grew to be 8 to 9 m long as adults, much larger than extant sirenians. Georg Steller’s writings contain two contradictory estimates of weight: 4 and 24.3 metric tons (4.4 and 26.8 short tons). This size made the sea cow one of the largest mammals of the Holocene epoch, along with whales. The sea cow’s large size was likely an adaptation to reduce its surface-area-to-volume ratio and conserve heat. Unlike other sirenians, Steller’s sea cow was positively buoyant, meaning that it was unable to completely submerge.

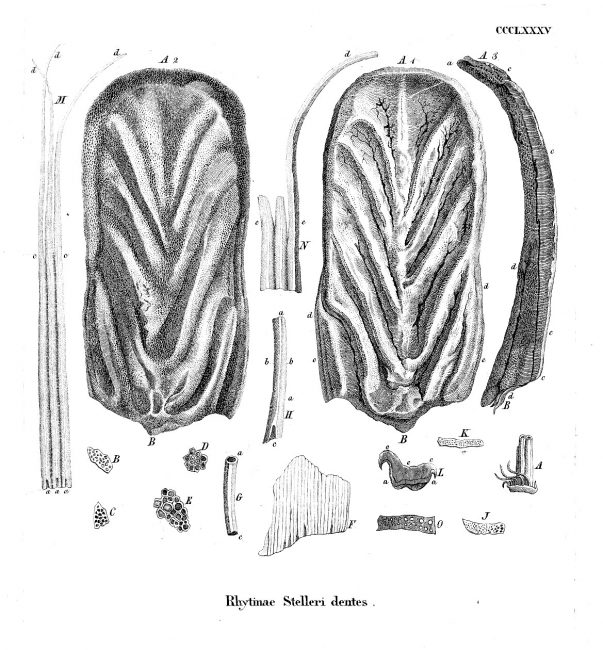

Hydrodamalis gigas Tooth, from Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur / mit Beschreibungen von Dr. Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber fortgesetzt von Dr. Johann Andreas Wagner. – 1840–1855

The teeth were completely receded in adaptation to the soft seaweed food; the animal crushed the seaweed between two horny chewing plates with which the palate was lined. The forearms ended in atrophied metacarpal bones, the Steller manatee no longer had finger bones. Two atrophied pelvic bones had remained of the rear extremities, while front oar fins were present, but greatly reduced in size compared to those of other manatees. The Steller’s manatee had a transverse, forked tail fin almost 2 meters wide. The skin was several centimeters thick to the protection from injuries at rocks and ice, possessed a thick fat layer for isolation reasons and had a bark-like consistency. The colour was dark brown.

Reconstruction of Steller measuring a Steller’s sea cow on Bering Island, July 12, 1742. from Leonhard Stejneger, Steller’s Journal of the Sea Voyage from Kamchatka to America, p. 228

On the Beasts of the Sea

Based on these and other observations, Georg Wilhelm Steller later wrote De Bestiis Marinis (‘On the Beasts of the Sea’), describing the fauna of the island, including the northern fur seal, the sea otter, Steller’s sea lion, Steller’s sea cow, Steller’s eider and the spectacled cormorant. Steller claimed the only recorded sighting of the marine cryptid Steller’s sea ape.

Legacy of the Great Nordic Expedition

More than his numerous scientific writings, which he produced during the Great Nordic Expedition and which have been preserved in part, it is above all his account of the Bering’s Alaskan expedition and its dramatic end, which has carried on his name to this day. There were also other records of this voyage made by nautical experts. But they strongly emphasized the purely technical aspects of the ride. Steller provided a more comprehensive picture of the circumstances and events by incorporating, in addition to the descriptions of natural history, moods and judgements on events that did not diminish the purely objective content of his report, but rather contributed to the creation of an overall picture.

References and Further Reading:

- [1] [In German] Auf der Spur von Steller at National Geographic Germany

- [2] Steller’s Sea Cow at the AMIQ Institute

- [3] Steller’s Sea Cow at Animal Diversity Web

- [4] [In German] Steller’s Life and Work at the International Georg-Wilhelm-Steller-Gesellschaft

- [5] Vitus Bering and his Arctic Expeditions, SciHi Blog

- [6] Steller’s Sea Cow at Wikidata

- [7] Georg Wilhelm Steller at Wikidata

- [8] Literature by or about Georg Wilhelm Steller at the German National Library

- [9] Georg Wilhelm Stellers Ausführliche Beschreibung von sonderbaren Meeresthieren mit Erläuterungen und nöthigen Kupfern versehen. Carl Christian Kümmel, Halle 1753

- [10] George Wilhelm Stellers. Beschreibung von dem Lande Kamtschatka dessen Einwohnern, deren Sitten, Rahmen, Lebensart und verschiedenen Gebräuchen. Johann Georg Fleische, Frankfurt und Leipzig 1774

- [11] Works by or about Georg Wilhelm Steller, at Wikisource

- [12] Dr. Jonathan Hoffman, November 2018 From Shore to Sea Lecture: Research on an Ancient Sea Cow Discovered, channelislandsnps @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of the Great Norther Expedition, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #30 | Whewell's Ghost