William Buckland (1784 – 1856)

On March 12, 1784, English theologian, geologist and eccentric palaeontologist William Buckland was born, who wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus.

“Geology holds the keys of one of the kingdoms of nature; and it cannot be said that a science which extends our Knowledge, and by consequence our Power, over a third part of nature, holds a low place among intellectual employments.”

— William Buckland, as quoted in [10]

Youth and Education

Buckland grew up in Axminster, Devon, UK, and spent a lot his his childhood days together with his father, a rector, hiking and collecting ammonites and several other shells they found along the way. Buckland received most of his formal education at St Mary’s College in Winchester, but improved his knowledge in natural history in his free time. Through a scholarship, he was able to attend Corpus Christi College at Oxford, where Buckland was next to his formal studies for the ministry also taught in mineralogy and chemistry by John Kidd. Having taken his BA in 1804, he went on to obtain his MA degree in 1808. He then became a Fellow of Corpus Christi in 1809, was ordained as a priest.

Buckland’s Geological Excursions

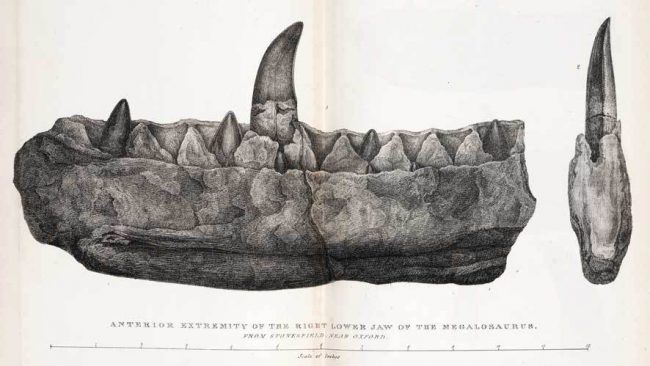

In 1808, Buckland’s frequent geological excursions in England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland began. Five years later, he was appointed Reader of Mineralogy. His lectures were always popular among the students as well as among fellow scientists due to the use of numerous diagrams and a great amount of paleontology and geology, lively combined with his mineralogy topics. While on a trip across Europe, Buckland got to know several scientists, one of them being Georges Cuvier,[8] who visited Buckland at Oxford in 1818, the same year as Buckland was elected fellow of the Royal Society. The French naturalist and zoologist was shown a collection of bones found at Stonesfield, which depicted a great milestones to both, Cuvier’s and Buckland’s career. As later on proved, these bones belonged to the Megalosaurus.

Engraving of the fragment of the right lower jaw of Megalosaurus of Stonesfield near Oxford described by Buckland from the first description Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield of 1824.

The Uniformitarism vs Catastrophism Controversy

In his inaugural lecture for his readership in geology, published in 1820 as Vindiciæ Geologiæ; or the Connexion of Geology with Religion, Buckland explained, both justifying the new science of geology and reconciling geological evidence with the biblical accounts of creation and Noah’s Flood. At a time when others were coming under the opposing influence of James Hutton‘s theory of uniformitarianism(in contrast to catastrophism), Buckland developed a new hypothesis that the word “beginning” in Genesis meant an undefined period between the origin of the earth and the creation of its current inhabitants, during which a long series of extinctions and successive creations of new kinds of plants and animals had occurred. Thus, his catastrophism theory incorporated a version of Old Earth creationism or Gap creationism. Buckland believed in a global deluge during the time of Noah but was not a supporter of flood geology as he believed that only a small amount of the strata could have been formed in the single year occupied by the deluge.

Duria Antiquior – A more Ancient Dorset, 1830 watercolor by Henry De la Beche, based on Buckland’s account of Mary Anning’s discoveries

More Dinosaur History

Back to the Megalosaurus. Buckland was not the first to observe pieces of the dinosaur. In 1676, several pieces were already sent to Robert Plot, back then also professor at the University of Oxford. But even though he correctly identified the bones as the lower extremity of a rather large animal, he incorrectly assumed them to be part of a giant human as mentioned in the Bible. When Buckland got access to the bones, found in 1815 at the Stonesfield quarry, he realized that these were parts of a giant animal compared to a lizard. His researches on the lower jaw, fragments of the pelvis, scapula and hind limbs were published in Transactions of the Geological Society in 1824, which increased his reputation critically.

Reconstructing the Megalosaurus

Reconstructing the Megalosaurus was difficult, since no scientist ever pictured a creature of this kind. It was often illustrated as a dragon like animal with giant heads walking on all fours. The illustrations became more accurate, when further findings of similar species were made in North America in the 19th century. However, further research revealed that the Megalosaurus was to be classified as a carnivore member of the Jurassic period 166 Million years ago and to its main habitat belonged England, Portugal, and France.

Later Years

Buckland however, became widely known for his achievements and turned somewhat into a scientific celebrity, occupied with high positions at Oxford, the Royal Society, the British Association, and the Geological Society. He continued his lectures gathering even more students and scientists together. Buckland began working together with Charles Lyell, and explained numerous geological phenomena considering Swiss glaciers. He continued his career as Dean of Westminster in 1845 while improving the quality of the institution’s education and lecturing at Oxford.

Buckland’s Eccentricities

William Buckland was a dazzling personality and known as an eccentric, who also conducted field research in academic robes and cylinders and entertained evening parties with amusing lectures on his latest bone finds. He always carried a blue bag with him, which he filled with geological finds collected along the way. In his Oxford and Westminster premises, Buckland housed a large number of partly exotic animals that often roamed freely[2]. Buckland was also known for his gastronomic experiments. He is said to have had the ambition to eat his way through the entire animal kingdom by eating one specimen of each known species. Around the end of 1850, William Buckland contracted a disorder of the neck and brain, and died of it in 1856.

“The taste of mole was the most repulsive I knew until I tasted a bluebottle [fly].”

— William Buckland, as quoted in The Violinist’s Thumb 2012 by Sam Kean, p. 204

Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] William Buckland – Oxford University Museum of Natural History

- [2] William Buckland in Retrospect

- [3] Megalosaurus at Animal Planet

- [4] Édouard Lartet – a pioneer of Paleolithic archaeology, SciHi Blog, April 15, 2017

- [5] Evolution is not Reversible – Louis Dollo, SciHi Blog, December 7, 2016

- [6] Charles Lyell and the Principles of Geology, SciHi Blog, November 14, 2012

- [7] William Buckland at Wikidata

- [8] Georges Cuvier and the Fossils, SciHi Blog, August 23, 2013.

- [9] The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland… By his daughter, Mrs. Gordon, (London : J. Murray, 1894)

- [10] Granville Penn, A Comparative Estimate of the Mineral and Mosaical Geologies (1825) , p. 8

- [11] Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, TED @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of Parson Naturalists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #30 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: William Buckland – Ein Extravagant der frühen Saurierforschung