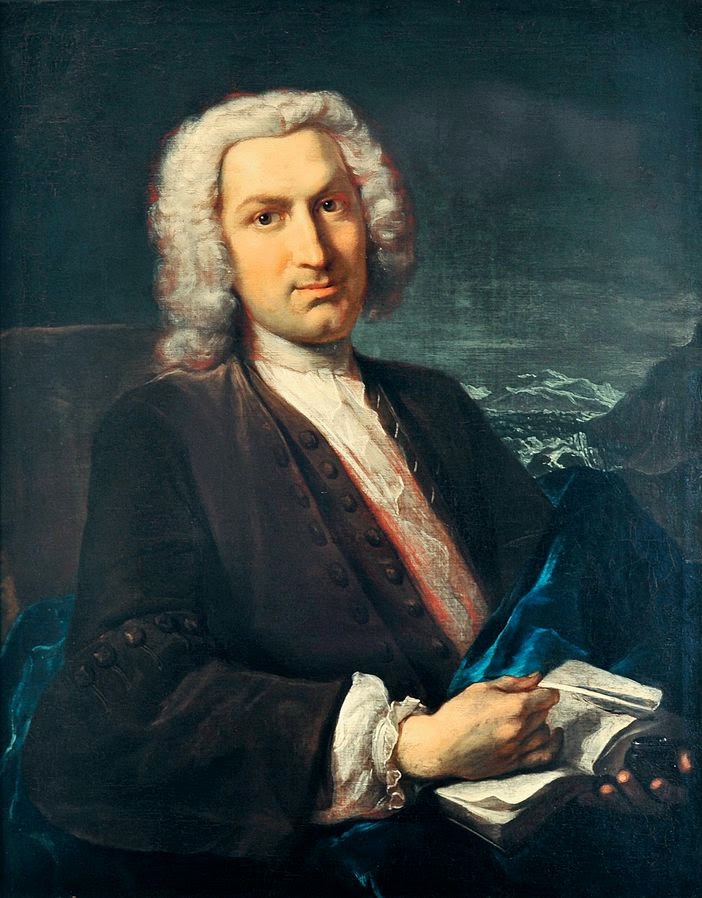

Albrecht von Haller (1708 – 1777), painting by Johann Rudolf Huber (1736)

On October 16, 1708, Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist and poet Albrecht von Haller was born. He made prolific contributions to physiology, anatomy, botany, embryology, poetry, and scientific bibliography. Moreover, he is often referred to as the “Father of modern Physiology“.

Albrecht von Haller – Youth and Education

Albrecht von Haller came from a Bernese patrician family, which had belonged to the Burgerschaft of the city of Bern since 1548. His parents were Niklaus Emanuel Haller (1672-1721), who held the office of bailiff under the Bernese bailiff Hieronymus Thormann (1658-1733), and his first wife Anna Maria Engel (1681-1708). It is said that Albrecht von Haller learned Greek and Hebrew at the age of 10 and authored translations from Ovid, Horace and Virgil before turning 15. However, his interest turned to the field of medicine soon and the young man enrolled at the University of Tübingen, Germany when he was approximately 16 years old. In 1725, Haller continued his studies at Leiden where Bernhard Siegfried Albinus taught anatomy.[7] In 1727, in his final thesis under the supervision of Herman Boerhaave,[8] Haller proved that the salivary duct, which Georg Coschwitz claimed to have discovered was simply a blood-vessel.

Botany and Poetry

Haller went to London, Paris, and Basel in order to meet contemporary scientists and increased his interest in higher mathematics and botany. He returned to Switzerland in 1728 to study mathematics and botany at the University of Basel. The scientist began collecting plants mostly in Switzerland which became the basis his great work on the flora of Switzerland. Next to his works on botany, Haller also used the experiences he made in the Alps to create several poems. ‘Die Alpen‘ was published in his 1732 edition of ‘Gedichte‘. It is assumed that Haller’s poem was one of the first signs of the increasing appreciation of the mountains and is considered historically relevant. [1] There was probably no poet of German tongue in the 18th century who did not know this poem.

Illustration from C.J. Rollinus in Haller’s book Icones anatomicae from 1756

Academic Career

From 1729 Haller worked as a general practitioner in Bern, received the position of city doctor in 1734 and became head of the library in Bern in 1735. In 1736 Haller moved to the Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg to the recently founded University of Göttingen to the chair of anatomy, surgery and botany. He established an Anatomical Theater there in 1738, a botanical garden a year later, and built up a collection for an anatomical “Cabinet.” Haller was appointed honorary doctor as well as personal physician to George II. Haller turned down appointments to Utrecht and Oxford. Emperor Franz I elevated him to hereditary nobility in 1749. Next to publishing many poems and conducting a monthly journal to which he contributed around 900 articles. In 1751, he was elected president for life of the newly founded Royal Society of Sciences at Göttingen. [3] Haller used his authority as a naturalist to defend the Christian religion against many a criticism from Voltaire.[9] On January 10, 1750, he was elected a member (matriculation no. 560) of the Leopoldina with the academic epithet Herophilus III.

Back in Switzerland

However, it is also known that Haller never really felt home in Göttingen and moved back to Switzerland in 1753. Albrecht von Haller was known for his experimental studies. He managed to analyze the irritability of muscle and the sensibility of nerves, studying circulation time and the automatic action of the heart. It is assumed that Haller was the first to give detailed explanation of respiration. He published his famous eight-volume ‘Elementa Physialogiae Carports Hamani’ (Elements of Physiology) in the late 1750s, which went through new editions into the 20th century, Haller provided a critical compilation of the anatomical-physiological knowledge of his time. For the Yverdon Institute and the supplement volumes of the Paris Encyclopédie, Haller wrote about 200 encyclopedia entries, some of considerable length, on the fields of anatomy and physiology. In addition, he compiled three medical bibliographies in which the entire medical literature up to his time was listed and critically annotated.

Scientific Achievements

Haller’s importance in the history of medicine lies primarily in his role as an anatomical scientist. By dissecting nearly 400 cadavers, he succeeded in depicting the course of the arteries in the human body with previously unattained perfection. Further studies were devoted to the flow of blood, the structure of bone and embryonic development. The systematic performance of numerous animal experiments to determine the sensitivity and irritability of individual parts of the body, the results of which triggered a Europe-wide controversy, also made him the founder of modern experimental physiology. Haller was the first to recognize the importance of blood vessels for the healing of bone fractures through experimental investigation and described more precisely than his processes the changes to be found in the vessels in arteriosclerosis and visible as hardenings. As a scientific organizer, he made a decisive contribution to the institutional realization of the ideal of the unity of research and teaching through his activities in the Göttingen Society of Sciences.

An Avid Letter Writer

Haller was one of the most active correspondents of the 18th century. This is evidenced by over 12,000 letters addressed to him and 17,000 written by him, which make up that part of Haller’s estate that is now kept in the Bern Burgerbibliothek. The content was essentially for scholarly exchange, as was generally cultivated by scholars in the 18th century. His letters to Johannes Gessner, Charles Bonnet, Simon-Auguste Tissot, Eberhard Friedrich von Gemmingen, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Giovanni Battista Morgagni, Ignazio Somis (1718-1793), Carl von Linné, Christian Gottlob Heyne and Marc Antonio Caldani (1725-1813) are worth mentioning. Haller was aware of the scientific importance of his collection of letters. He himself began to publish many of his letters in Latin and German in several volumes. Many of his correspondences were intended for later publication from the very beginning. During Haller’s lifetime and also since, several correspondences have been edited.

Later Years

In Bern, Haller held the position of town hall official from 1753, became a school councilor in 1754, and head of the orphanage in 1755. After his term of office expired, he became director of the Roche salt mines in 1758. He declined the post of chancellor in Göttingen, which was offered to him, after fierce opposition from his family. His last years were marked by illness.

Peter Harrison – Science, Religion and Modernity [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Haller, Albrecht von“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 855–856.

- [2] Albrecht von Haller at Famous Scientists

- [3] Albrecht von Haller at the University of Göttingen

- [4] Carl Ludwig – Pioneer of Modern Physiology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Albrecht von Haller at Wikidata

- [6] Peter Harrison – Science, Religion and Modernity, University of Edinburgh @ youtube

- [7] Bernard Siegfried Albinus and his Anatomic Works, SciHi Blog

- [8] The Clinical Teaching of Herman Boerhaave, SciHi Blog

- [9] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [10] Emil Blösch: Haller, Albrecht von (Mediziner). In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 10, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1879, S. 420–427.

- [11] Eduard Fueter, Adalbert Elschenbroich: Haller, Albrecht von. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, S. 541–548

- [12] Boury, Dominique (2008-12-01). “Irritability and Sensibility: Key Concepts in Assessing the Medical Doctrines of Haller and Bordeu”. Science in Context. 21 (4): 521–535.

- [13] Haller, Albrecht von (1780). “Letters from Baron Haller to His Daughter on the Truths of the Christian Religion”. J. Murray and William Creech.

- [14] Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [15] Timeline of Albrecht von Haller via Wikidata