Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (1888-1934)

On December 28, 1888, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau was born. He was one of the most influential German film directors of the silent era, and a prominent figure in the expressionist movement in German cinema during the 1920s. Murnau‘s best known work was his 1922 film Nosferatu, an adaptation of Bram Stoker‘s Dracula.[6]

Becoming Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau was actually born as Friedrich Wilhelm Pumpe in Bielefeld, Germany. He grew up in a wealthy middle-class family; his father was a cloth manufacturer, his mother a teacher. In 1892 his family moved to Kassel. From 1898 to 1902 Plumpe lived in the Elfbuchenstraße in Kassel. After attending grammar school in Kassel, he began studying philology and art history in Berlin and Heidelberg. The famous director Max Reinhardt noticed his talents during a play at university and occupied the young Pumpe as director’s assistant and actor.[4] During this period, he also changed his name to Murnau (after the city Murnau in Bavaria). This was, besides the artistic aspect, a clear sign of the break with his parents, who did not want to accept his homosexuality as well as his acting and directing ambitions. Among his artist friends were the author Else Lasker-Schüler and the expressionist painters of the group Der blaue Reiter.[5]

First World War and Internment

In the First World War Murnau participated as a lieutenant in the 1st Ward Regiment on foot and from 1917 as a fighter pilot until he landed on the territory of neutral Switzerland either intentionally or due to a navigational error. There he was first interned in Andermatt but after winning a production competition for the patriotic play Marignano he was able to work at the Lucerne theater. The war experiences were formative for Murnau as for many of his generation. Many see his experiences during the war a significant influence to his later movies, especially Nosferatu.

First Movies

Murnau came back to Berlin in 1919 and began working on his first movie, “The Boy in Blue“. Unfortunately, this movie is lost on this day, but it is known that Thomas Gainsborough‘s painting “The Blue Boy” and Oscar Wilde‘s novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray” were inspirations for Murnau to create this film. With the movie Der Bucklige und die Tänzerin (The hunchback and the Dancer) began a very fruitful cooperation with the screenwriter Carl Mayer who wrote the books for six more movies of Murnau. Other artists with whom Murnau preferred to work together are screenwriter Thea von Harbou, cameraman Carl Hoffmann and actor Conrad Veidt.

Success in Germany

Soon, Murnau started working for UFA and created several works for them including “The Last Laugh” in which Emil Jannings embodies a hotel doorman who is degraded to a toilet attendant and breaks. There, Murnau used the completely new unchained camera technique that opened up whole new perspectives to the art of film in the 1920s. For example, to follow the smoke of a cigarette, Murnau’s camera operator Karl Freund strapped the camera to a fire ladder and moved it. Also, he introduced the subjective camera in the movie that illustrated the plot from the perspective of one specific actor. Murnau became famous, also because he needed almost no subtitles for the audience to understand the plot, which was remarkable back then. Murnau finished the series of his in Germany created movies in 1926 with Tartüff after Molière und Faust – eine deutsche Volkssage (Faust – A German Folk Tale).

Murnau in Hollywood

Murnau’s successes in Germany and especially the American version of The Last Laugh in 1925 had drawn Hollywood’s attention to him. Murnau received a contract offer from the American producer William Fox who assured him full artistic freedom. As a result, the movie “Sunrise” won three Oscars during the very first Academy Award ceremony in 1929, but did not fully meet commercial expectations. For this reason and because of the increasingly difficult economic situation of the Fox company and the situation in Hollywood on the threshold of the sound film, Murnau had to accept increasing interventions in his artistic concept in his following films. In the film City Girl he was even replaced as director and without his influence a sound version was produced afterwards. Disappointed by the constraints of Hollywood, Murnau cancelled his contract with Fox in 1929

Bora Bora and Tabu

Together with documentary film pioneer Robert J. Flaherty, Murnau travelled to Bora Bora to make the film Tabu in 1931. Flaherty left after artistic disputes with Murnau who had to finish the movie on his own. The movie was censored in the United States for images of bare-breasted Polynesian women. The film was originally shot by cinematographer Floyd Crosby as half-talkie, half-silent, before being fully restored as a silent film — Murnau’s preferred medium. The movie was a success but Murnau was broke. Paramount took over this film and offered Murnau a contract for 10 years.

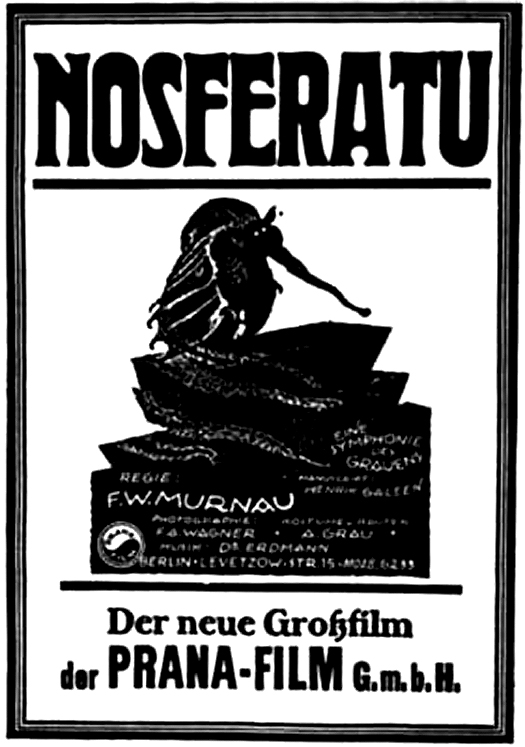

A promotional film poster for Nosferatu.

Nosferatu

On this day, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau is mostly remembered for his movie “Nosferatu“. It starred Max Schreck as the vampire Count Orlok and was an unauthorized adaption of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The company producing the film was “Prana Film” and co-founded by Albin Grau. Since a Serbian farmer told him that his father was a vampire, he wanted to shoot a vampire film. Nosferatu’s preview premiered on 4 March 1922 in the Marmorsaal of the Berlin Zoological Garden. This was planned as a large society evening entitled Das Fest des Nosferatu (Festival of Nosferatu), and guests were asked to arrive dressed in Biedermeier costume. The cinema premiere itself took place on 15 March 1922 at Berlin’s Primus-Palast. The studio behind Nosferatu, Prana Film, was a short-lived silent-era German film studio founded in 1921 by Enrico Dieckmann and occultist-artist Albin Grau, named for the Hindu concept of prana. Although the studio’s intent was to produce occult- and supernatural-themed films, Nosferatu was its only production the company declared bankruptcy after Stoker’s estate, acting for his widow, Florence Stoker, sued for copyright infringement and won. The court ordered all existing prints of Nosferatu burned, but one purported print of the film had already been distributed around the world. This print was duplicated over the years, kept alive by a cult following, making it an example of an early cult film. The work remains an important piece of the expressionist art and Murnau reinforced into the public eye. The press praised it as a masterpiece with overall technical perfection.

The End

Murnau did not live to see the premiere of Tabu on 18 March 1931. On 11 March 1931, shortly before a European promotion tour of Murnau, his servant, 14-year-old Filipino Garcia Stevenson, lost control of the car in which they were driving on the coastal road southeast of Santa Barbara (California), causing it to collide head-on with a truck. Murnau died of his injuries a few hours later. Only eleven people said goodbye to him on March 19, including Greta Garbo.

David Thorburn, 7. German Film, Murnau , [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] German Murnau Society

- [2] Nosferatu at the Imdb

- [3] Friedrich Murnau und seine Filme

- [4] Max Reinhardt – From Bourgeois Theatre to Metropolitan Culture, SciHi Blog

- [5] Franz Marc – German Expressionism and Der blaue Reiter, SciHi Blog

- [6] Count Vampyre from Styria – or what Bram Stoker did not write, SciHi Blog

- [7] Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau at Wikidata

- [8] Timeline of movies by F. W. Murnau, via Wikidata

- [9] F. W. Murnau on IMDb

- [10] “F. W. Murnau Killed in Coast Auto Crash”. The New York Times. March 12, 1931.

- [11] A 1947 version of the 1922 film Nosferatu, with added English titles. No sound.

- [12] David Thorburn, 7. German Film, Murnau, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube