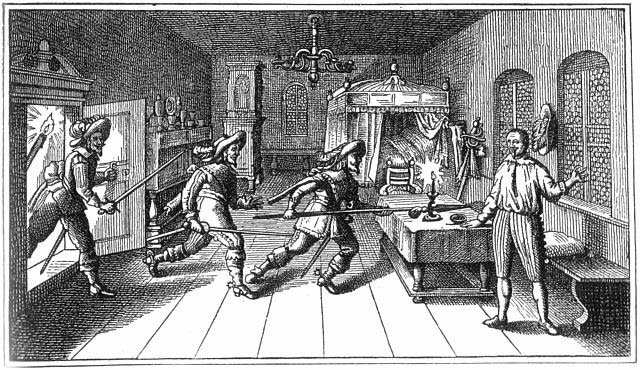

The Assassination of Albrecht von Wallenstein, February 25, 1634

On February 25, 1634, Bohemian military leader and politician Count Albrecht von Wallenstein was assassinated at Cheb in Bohemia. An imperial generalissimo of the Thirty Year’s War, and Admiral of the Baltic Sea, he had made himself ruler of the lands of the Duchy of Friedland in northern Bohemia. Wallenstein found himself released from imperial service in 1630 after Emperor Ferdinand grew wary of his ambition.

“We act as we must. So let us do what is necessary, with dignity, with firm steps.”

– Wallenstein in Friedrich Schiller, Wallenstein’s Death (1799)

Family Background and Early Years

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius, called Wallenstein, was born on 24 September 1583 in Hermanitz an der Elbe. He was descended from the old Bohemian lords of Waldstein. Wallenstein’s father Wilhelm IV Baron von Waldstein, royal Bohemian captain of the Königgrätzer Kreis, deceased in 1595, was married to Margaretha Freiin Smirziczky von Smirzicz. Wallenstein’s testamentary guardian Heinrich Slavata of Chlum and Koschumberg, a brother-in-law of his mother, took Albrecht to himself at Koschumberg Castle and had him educated by Bohemian brothers together with his own son. In addition to his Czech mother tongue, Wallenstein also learned German, Latin and Italian. In autumn 1597 he was sent for further education to the Protestant Latin School in Goldberg in Silesia and in midsummer 1599 to the Protestant Academy in Altdorf, near Nuremberg, which Wallenstein had to leave already in April 1600, after he had been noticed several times by acts of violence. In the meantime his guardian had died, and Wallenstein went on a Grand Tour until 1602, of which no further details have survived. He apparently studied at the Universities of Padua and Bologna, since he then had a comprehensive education and knowledge of the Italian language.

Service with various Lords

At the beginning of July 1604, on the recommendation of his cousin, the imperial master stallion master Adam von Waldstein, Wallenstein became ensign in a regiment of imperial Bohemian footmen, who moved to Hungary on the orders of Emperor Rudolf II. The army, which in 1604 set out against the rebellious Hungarian Protestants, was commanded by Lieutenant General Georg Basta. During this campaign under the command of Basta, Wallenstein learned the tactics of Transylvanian light cavalry and observed the then 45-year-old commander of the imperial artillery, Colonel Count von Tilly. The campaign ended prematurely due to an early onset of winter, and the army withdrew to its winter quarters north of Kaschau in Upper Hungary. Wallenstein was promoted to captain and severely injured in battles near Kaschau.

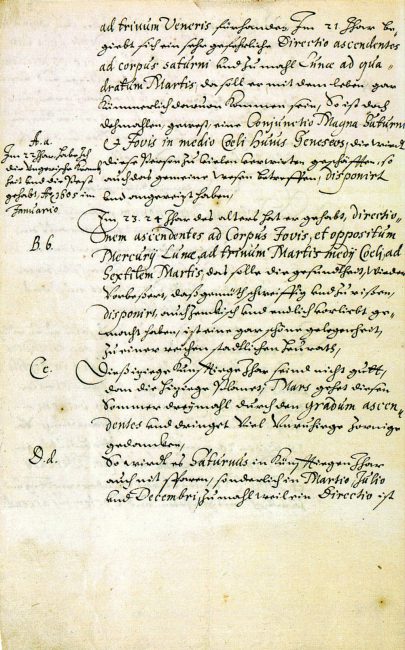

After the demobilization of the Bohemian troops in 1605, Wallenstein was appointed by the Bohemian estates as the head of a regiment of German infantry. The peace with the Hungarians forced by Matthias, the brother of Emperor Rudolf, abruptly ended Wallenstein’s first military career. During his stay in Prague, Wallenstein had his first horoscope exhibited by the imperial court mathematician Johannes Kepler.[4] The horoscope characterizes Wallenstein as a man of great ambition and power. Dangerous enemies would appear to him, but he would usually win. Based on recommendations, Wallenstein was made chamberlain of Archduke Matthias and married Lukretia von Witschkow, a rich and older widow. The enormous fortune of the Lukretia is estimated at about 400,000 guilders and created the economic basis for the rise of Wallenstein. After emperor Rudolf’s death and the election of his brother Matthias as the new emperor in May 1612, Wallenstein became imperial treasurer. In 1612 he was elected to a committee for legal disputes in Moravia, but did not develop any other activities in the political field. Wallenstein’s wife Lukretia died on 23 March 1614. In 1615 he was appointed by the Moravian estates to the position of chief of a regiment of the Foot People. In fact, the position of chief was only on paper, and his appointment was not a result of special military ability, but showed his financial possibilities, since he would have had to set up this regiment at his own expense in case of war.

Extract from the first horoscope for Wallenstein by Johannes Kepler, the marginal notes are by Wallenstein, 1608

Military Career

Wallenstein’s first chance to distinguish himself in the military arena came in 1615 when Archduke Ferdinand, later Emperor Ferdinand II, became involved in the Friulian war against Venice, the naval power dominating the Mediterranean. In February 1617 the military and financial situation and the supply of the troops became so bad that Ferdinand took the utmost means and appealed to his estates and vassals to send him troops at his own expense. Only Wallenstein complied with the request for help. Ferdinand remembered the help of his treasurer even later. Ferdinand was impressed not only by the fact that Wallenstein had recruited troops, but also that he had led them to Friuli and into battle himself. In the same year Ferdinand therefore commissioned Wallenstein to draft a new article letter, a kind of code of law for the mercenary troops. The Wallenstein Reutter law later became binding for the entire imperial army and was only replaced by a new martial law in 1642.

Portrait of Wallenstein (1583 – 1634)

The Thirty Years’ War

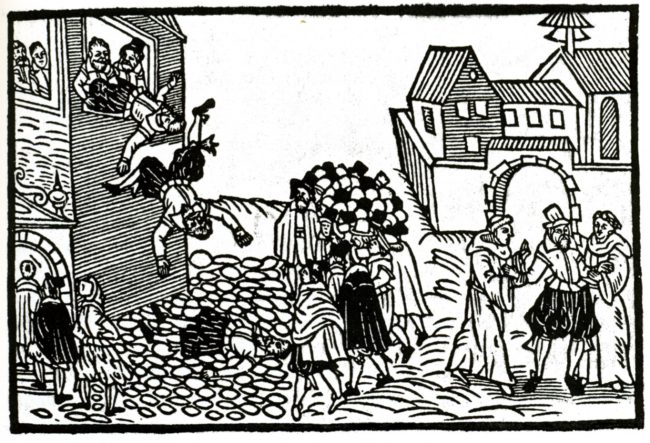

Meanwhile, the confessional and political conflicts in Bohemia continued unabated. Thus in 1617 Emperor Matthias succeeded in having the decisive Catholic Ferdinand crowned King of Bohemia as his successor. The Bohemian estates only reluctantly agreed to Ferdinand’s election, because he hated the letter of majesty and did everything to recatholicize Bohemia. Only one year later the evangelical estates of Bohemia therefore went into open rebellion. An expression of this was the defenestration of Prague on 23 May 1618. Wallenstein associated himself with the cause of the Catholics and the Habsburg dynasty. He managed to bring the Moravian treasure-chest to Vienna in order to prove his loyalty to Ferdinand. Next, Wallenstein was able to secure his family’s land, confiscated large tracts of Protestant lands and named his territory Friedland in northern Bohemia. In 1623, Wallenstein was elevated by Ferdinand to the longed-for rank of imperial prince. The old princes of the empire, in particular the electors, were angry at this rise in rank and in some cases refused to address the prince as he deserved. Wallenstein became the Duke of Friedland in 1625, offered to raise a whole army for the imperial service in the same year and recruited about 50,000 men. When he was rewarded the Duchies of Mecklenburg, many high born rulers of German states were quite shocked. Also Wallenstein started to lose battles, which made him a host of enemies, both Catholic and Protestant princes and non-princes.

The Defenestration of Prague on a contemporary woodcut, 1618

Wallenstein’s Decline and Reinstallation

Ferdinand started suspecting, that Wallenstein intended to take control of the Holy Roman Empire and planned to dismiss him. At the Regensburg Electors’ Day in the summer of 1630, the Electors (supported by a French delegation with Père Joseph) forced the emperor to dismiss Wallenstein, who had become too powerful for them, and to reduce their own troops. However, he had to be called into field again. In the early summer of 1630, the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus landed on the island of Usedom and thus actively intervened in the war. In the autumn of 1630 he occupied large parts of Mecklenburg, except for the fortified ports of Rostock and Wismar. In 1631 Gustavus Adolphus inflicted numerous defeats on the imperial troops. The Swedes moved on via Thuringia to Franconia and Bavaria, the Saxons invaded Bohemia – under the command of Wallenstein’s former troop leader and confidant Arnim. In this almost hopeless situation, only Wallenstein seemed to be able to turn the tide once more in favour of the emperor. Wallenstein was appointed Generalissimus with further powers: he received unrestricted command of the army. With a new army, Wallenstein finally was able to advance against Gustavus Adolphus, who was killed in the confused melee of the decisive Battle of Lützen.[5]

Negotiations with the Enemy and High Treason

It is assumed that by this time, Wallenstein indeed started preparing to desert the Emperor and that he started negotiating with France, Saxony, Brandenburg, and Sweden. In the campaigning of 1633, Wallenstein’s apparent unwillingness to attack the enemy caused much concern in Vienna and in Spain. At this time the dimensions of the war had grown more European, and Wallenstein had begun preparing to desert the Emperor. He expressed anger at Ferdinand’s refusal to revoke the Edict of Restitution. Soon, Wallenstein became aware of the fact that the Emperor was planning to replace him, but hoped that his army would stay loyal to him. In December Wallenstein retired with his army to Bohemia, around Pilsen (now Plzeň). Vienna soon definitely convinced itself of his treachery, a secret court found him guilty, and the Emperor looked seriously for a means of getting rid of him. Wallenstein was aware of the plan to replace him, but felt confident that when the army came to decide between him and the Emperor the decision would be in his favour. However, on 24 January 1634 Wallenstein was removed from his commands and was charged with high treason. Wallenstein lost his army’s support, but still intended to meet the Swedes under Duke Bernhard in Cheb. Unfortunately for him, he was assassinated after his arrival by Scottish and Irish officers on February 25, 1634. It is assumed on this day, that the Holy Roman Emperor did not command the murder. Still, he had given free rein to the party who he knew wished “to bring in Wallenstein, alive or dead” and the murderers were rewarded with wealth and honor.

Wallenstein’s Legacy

Wallenstein’s particular genius lay in recognizing a new way for funding war: instead of merely plundering enemies, he called for a new method of systematic “war taxes”. Even a city or a prince on the side of the Emperor had to pay taxes towards the war. Wallenstein understood the enormous wastage of resources that resulted from tax exactions on princes and cities of defeated enemies only, and desired to replace this with a “balanced” system of taxation; wherein both sides bore the cost of a war. He was unable to fully realize this ambition. His idea led to the random exploitation of whole populations on either side, until finally, almost fifteen years after his death, the war had become so expensive that the warring parties were forced to make peace.[6] Friedrich Schiller first set Wallenstein as a historian a monument in his extensive History of the Thirty Years’ War.[7] In his well-known drama trilogy Wallenstein’s Camp (Wallensteins Lager), a lengthy prologue, The Piccolomini (Die Piccolomini), and Wallenstein’s Death (Wallensteins Tod), he concentrated literarily on Wallenstein’s last lifetime. Nothing can be added to the literary account, as it largely corresponds to the historical facts.

The 30 Years’ War (1618-48) and the Second Defenestration of Prague – Professor Peter Wilson, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Wallenstein Biography

- [2] Literature on Wallenstein at the German National Library

- [3] Friedrich von Schiller’s Wallenstein Trilogy (in German) at Project Gutenberg:

- [4] And Kepler Has His Own Opera – Kepler’s 3rd Planetary Law, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Battle of Lützen and the Death of the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Peace of Westphalia and the End of the Thirty Year’s War, SciHi Blog

- [7] ‘Art is the Daughter of Freedom’ – Friedrich Schiller, SciHi Blog

- [8] Friedrich Schiller, The Camp of Wallenstein from Librivox

- [9] Albrecht von Wallenstein at Wikidata

- [10] Albrecht von Wallenstein at Reasonator

- [11] The 30 Years’ War (1618-48) and the Second Defenestration of Prague – Professor Peter Wilson, Gresham College @ youtube

- [12] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–282.

- [13] Karl Wittich: Wallenstein, Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 45, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1900, S. 582–641.

- [14] Battles of the Thirty Year’s War, via Wikidata