Aldus Manutius (1449 – 1515)

On February 6, 1515, Venetian printer and publisher Aldus Pius Manutius passed away, the Italian humanist, scholar, educator, and the founder of the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preservation of Greek manuscripts mark him as an innovative publisher of his age dedicated to the editions he produced. His enchiridia, small portable books, revolutionized personal reading and are the predecessor of the modern paperback.

Aldus Manutius’ Early Life

Aldus Manutius was born close to Rome in Bassiano between 1449 and 1452. Most of Manutius’s early life is rather unknown. He grew up in a wealthy family during the Italian Renaissance and in his youth was sent to Rome to become a humanist scholar. After studies in Ferrara, Rome and Verona, Manutius was granted citizenship of the town of Carpi in 1480 where he owned local property, and in 1482 he traveled to Mirandola for a time with his longtime friend and fellow student, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, where he stayed two years to study Greek literature.[1] Giovanni Pico and Alberto Pio’s families funded the starting costs of Manutius’s printing press and gave him lands in Carpi.

A Printing Shop in Venice

However, Manutius determined that Venice was the best location for his work, settling there in 1490. In Venice, Manutius began gathering publishing contracts, at which point he met Andrea Torresani, who was also engaged in print publishing. Torresani and Manutius became lifelong business partners, and for their first contract together Manutius hired Torresani to print the first edition of his Latin grammar book the Institutiones grammaticae, published on 9 March 1493.

The Aldine Press

The Aldine Press was originally owned half by Pier Francesco Barbarigo, the nephew of the current doge of the time, Agostino Barbarigo, and the other half by Andrea Torresani. Manutius owned one fifth of Torresani’s share. Manutius mainly was in charge of the scholarship and editing, leaving financial and operating concerns to Barbarigo and Torresani. In 1496, Aldus established his own location in a building called the Thermae in the Sestiere di San Polo. Manutius lived and worked in the Thermae to produce published books from the Aldine Press. This was also the location of the “New Academy”, where a group of Manutius’ friends, associates, and editors came together to translate Greek and Latin texts.

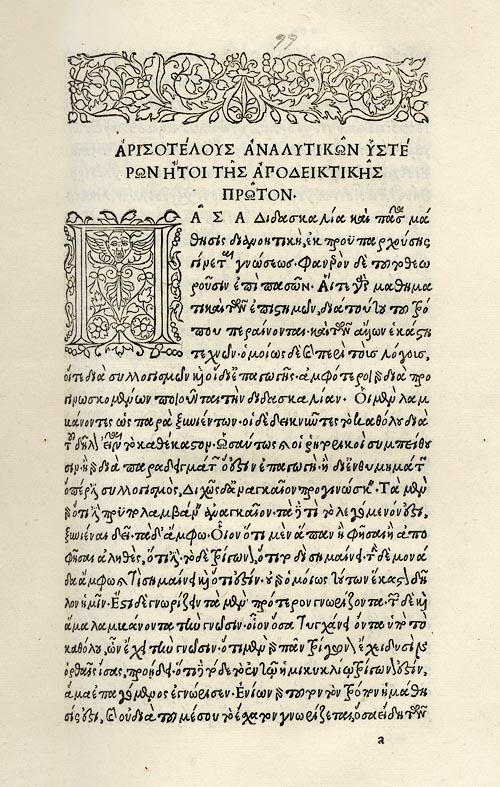

Aristotle printed by Aldus Manutius, 1495–98 (Libreria antiquaria Pregliasco, Turin)

How the Aldine Press Revolutionized Printing

In the Biblioteca Marciana there was an extensive collection of Greek manuscripts that had come to Venice through the foundation of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion.[2] With a circle of talented typographers, Manutius set about publishing these texts. His editions, the so-called Aldines, were innovative, among other things because of their small book format, which roughly corresponded to the octave and could be produced relatively cheaply. In 1495, the first prints in the world were published by him in Greek letters. With his prints of Greek and Latin works of antiquity and humanist authors such as Pietro Bembo [3] and Francesco Petrarch,[4] Manutius made a significant contribution to the development of humanism in Europe and to the rediscovery of antiquity in the Renaissance. At first the press printed new copies of Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek and Latin classics. Manutius also printed dictionaries and grammars to help people interpret the books, used by scholars wanting to learn Greek to employ learned Greeks to teach them directly. Erasmus was one of the scholars learned in Greek with whom the Aldine Press partnered in order to provide accurately translated text. The Aldine Press also expanded into current languages, mainly Italian and French.[5]

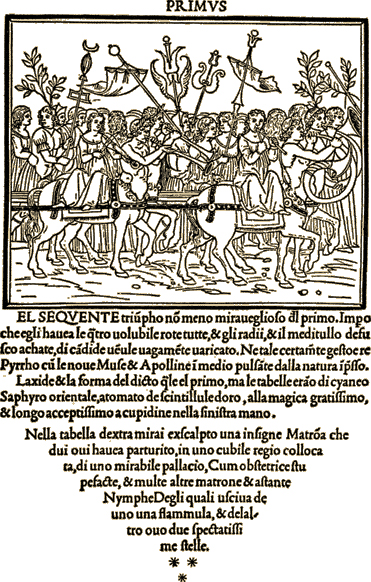

Book page by Francesco Colonnas Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, printed by Aldus Manutius

New Format, New Typeface

Manutius introduced the octave format for his books, while the manuscripts and incunabula had the (larger) quarto or folio format. He replaced the wooden inlays in the book covers with cardboard, so that the books were lighter in weight and easier to handle. Manutius described his new format of books as “libelli portatiles in formam enchiridii” (“portable small books in the form of a manual“). Enchiridion, described in A Legacy More Lasting than Bronze, also refers to a handheld weapon, a hint that Aldus intended the books in his Portable Library to be the weapons of scholars.

The new format required new types of printing. The italics used for the Aldines were based on the calligraphy of the time. Manutius replaced the so-called Gothic script, the textura derived from the manuscripts, which was common in the printing houses of the 15th century in the north, with new, ornate letters, today called Antiqua. In the 1501 edition of Virgil, he used italics for the first time, the invention of which was claimed by his type cutter Francesco Griffo after he divorced Manutius in 1502 in a dispute and moved to his rival Girolamo (Gershon) Soncino. Manutius’ editions of the works of Bembo and Petrarch were groundbreaking in the typographical design of punctuation, among other things through the regular use of the fixed point at the end of the movement and the use of the comma to mark periods within the movement.

The printed products with this trademark soon became known throughout Europe under the name of Aldine Press and enjoyed an excellent reputation both among fellow printers for their technical quality and the beauty of their design, and among scholars for their accurate text edition and moderate prices. The prices contributed to their great economic success. In a way, these books are the forerunners of paperbacks. Although Manutius had a printing privilege from the Republic of Venice, his printed products were quickly imitated, and in addition to the reprinting of the texts, the format, the types of printing and the publisher’s signet were also copied.

Aldus Manutius’ printer’s device – The Anchor and the Dolphin

The Anchor and the Dolphin

The printer symbol of the Aldine publisher’s device an anchor and a dolphin: The anchor is a symbol for slowness, the dolphin for speed. It had been in use since 1502 and was later used in numerous emblem books. The motto formulated in this picture is called Festina lente (hurry with time). It is ascribed to Augustus and is found in Sueton’s biographies and the Noctes Atticae of Aulus Gellius. Aldus’ signet, which stood for the care and beauty of his prints. Manutius’s editions of the classics were so highly respected that the dolphin-and-anchor device was almost immediately pirated by French and Italian publishers.

Manutius wrote his will on 16 January 1515 instructing Giulio Campagnola to provide capital letters for the Aldine Press’s italic type. He died the next month, 6 February, and “with his death the importance of Italy as a seminal and dynamic force in printing came to an end.” Torresani and his two sons carried on the business during the youth of Manutius’s children, and eventually Paulus, Manutius’s son, took over the business. The publishing symbol and motto were never wholly abandoned by the Aldine Press until the expiration of their firm in its third generation of operation by Aldus Manutius the Younger. The Aldine Press produced more than 100 editions from 1495 to 1505. The majority were Greek classics, but many notable Latin and Italian works were published as well.

If you want to learn more about Aldus Manutius, you might be also interested in the video How Aldus Manutius Saved Civilization with G. Scott Clemons

How Aldus Manutius Saved Civilization with G. Scott Clemons, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Pico della Mirandola and the 900 Theses, SciHi Blog

- [2] Basilios Bessarion and the Great Revival of Letters, SciHi Blog

- [3] Pietro Bembo and the Development of the Italian Language, SciHi Blog

- [4] Petrarch and the Invention of the Renaissance, SciHi Blog

- [5] Erasmus of Rotterdam – Prince of the Humanists, SciHi Blog

- [6] Symonds, John Addington (1911). “Manutius“. In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 624–626.

- [7] Exhibit on Aldus Manutius and his press at the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- [8] Works by Aldus Manutius at Archive.org

- [9] Aldus Manutius at Wikidata

- [10] How Aldus Manutius Saved Civilization with G. Scott Clemons, The Cooper Union @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of Printers of Incunabula, via DBpedia and Wikidata