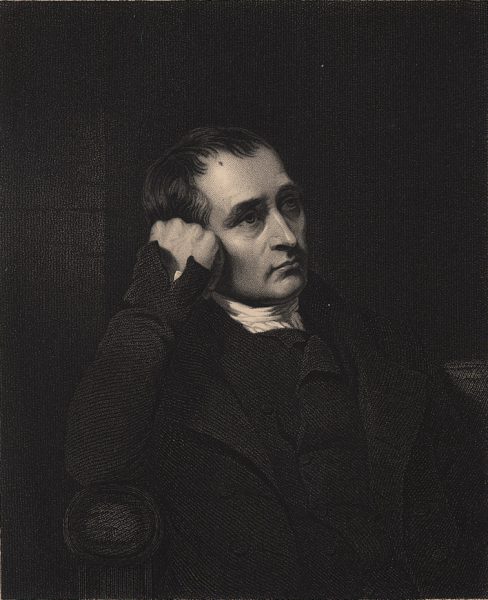

Samuel Crompton (1753-1827)

On December 3, 1753, English inventor and pioneer of the spinning industry Samuel Crompton was born. Building on the work of James Hargreaves and Richard Arkwright he invented the spinning mule, a machine that revolutionised the industry worldwide.

Early Years

Samuel Crompton was born as the oldest son among three siblings in Bolton, Lancashire, UK to George Crompton, a caretaker at nearby Hall i’ th’ Wood, and his wife Betty. While he was a boy he lost his father leaving his Mother Betty to fend for the family. She did this by doing what she knew. She continued the family trade of spinning and weaving and in 1764 she leased some land for small-scale farming.[3] Thus, the boy had to contribute to the family resources by spinning yarn, learning to spin on James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, a multi-spindle spinning frame and one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution.

The Mechanization of Spinning

Mechanization of spinning had already begun, but no one had yet developed a machine that solved the problem of producing strong fine yarns in quantities large enough to satisfy the demands of the mechanized looms.[3] Before the 1770s, textile production was a cottage industry using flax and wool. Weaving was a family activity. The children and women would card the fibre, which the women would spin into yarn; the male weaver would use a frame loom to weave this into cloth. This was then tentered in the sun to bleach it. The same production system was attempted with cotton, but the demand was too high, and with the invention by John Kay of the flying shuttle, which made the loom twice as productive, more cotton yarn was being woven than the traditional spinners could supply. There were two types of spinning wheel: the Simple Wheel, which uses an intermittent process, and the more refined Saxony wheel, which drives a differential spindle and flyer with a heck (an apparatus that guides the thread to the reels) in a continuous process. These two wheels became the starting point of technological development. Businessmen such as Richard Arkwright employed inventors to find solutions that would increase the amount of yarn spun, then took out the relevant patents [2]. The spinning jenny reduced the amount of work needed to produce yarn, with a worker able to work eight or more spools at once.

Crompton’s Spinning Mule

However, the deficiencies of the jenny imbued Crompton with the idea of devising something better, which he worked on in secret for five or six years. The effort absorbed all his spare time and money. About 1779, Samuel Crompton succeeded in producing a mule-jenny, a machine which spun yarn suitable for use in the manufacture of muslin. It was known as the muslin wheel or the Hall i’ th’ Woodwheel, from the name of the house in which he and his family now lived. The mule-jenny later became known as the spinning mule. The first mules were hand-operated and could be used at home. By the 1790s larger versions were built with as many as 400 spindles.[5] There was a strong demand for the yarn which Crompton was producing, but he could not afford a patent. The prying into his methods forced Crompton to choose between destroying his machine or making it public. He adopted the latter alternative after promises by a number of manufacturers to pay him for the use of the mule but all he received was about £60. He then resumed spinning on his own account, but with indifferent success.

Later Years

In 1800, a sum of £500 was raised for his benefit by subscription, and when in 1809, Edmund Cartwright, the inventor of the power loom, obtained £10,000 from parliament, Crompton determined to apply for a grant. In 1811, he toured the manufacturing districts of Lancashire and Scotland to collect evidence showing how extensively his mule was being used, and in 1812 parliament awarded him £5000. With the aid of this money, Crompton started a business as a bleacher and then as a cotton merchant and spinner, but without success.

Years later (in 1812), when there were at least 360 mills using 4,600,000 mule spindles, Parliament granted him £5,000. He used it to enter business, unsuccessfully, first as a bleacher and then as a cotton merchant and spinner.

Samuel Crompton died in poverty on 26 June 1827 in Bolton, aged 73.

Richard Bulliet, The Early Industrial Revolution, 1760-1851, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Samuel Crompton, British inventor, at Britannica online

- [2] Richard Arkwright – the Father of the Industrial Revolution, yovisto Blog, August 3, 2014.

- [3] The Life of Samuel Crompton, at Bolton Library and Museum Services.

- [4] “Crompton, Samuel.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Encyclopedia.com.

- [5] Samuel Crompton, at Spartacus Educational

- [6] Samuel Crompton at Wikidata

- [7] Richard Bulliet, The Early Industrial Revolution, 1760-1851, History W3903 section 001, Columbia University @ youtube

- [8] French, Gilbert J. (1859). The Life and Times of Samuel Crompton, Inventor of the Spinning Machine Called the Mule. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Company.

- [9] Daniels, George William (1929). The Early English Cotton Industry: With Some Unpublished Letters of Samuel Crompton. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

- [10] Timeline of spinning arts tools, via Wikidata