On September 5, 1765, French antiquarian, proto-archaeologist and man of letters Anne Claude de Tubières-Grimoard de Pestels de Lévis, comte de Caylus, marquis d’Esternay, baron de Bransac, was born. The Comte de Caylus is credited with being the first to conceive archaeology as a scientific discipline. Caylus was also a painter and an engraver, and he is also credited with finding a new process to inlay colors in marble.

The Comte de Caylus – Early Years

Anne Claude de Tubières-Grimoard de Pestels de Lévis was the only son of Marquise de Caylus, Anne III, of Tubières de Grimoard de Pestels de Caylus, lieutenant-general, and Marthe Le Valois de Villette, a niece of Madame de Maintenon and granddaughter of Agrippa d’Aubigné. When his father died, he was raised by his uncle, bishop of Auxerre. Still young, Caylus served in the army during the War of the Spanish Succession. After the peace of Rastatt was signed in 1714, he abandoned a promising military career to devote himself to the study of the arts. He travelled to England, Germany, Italy, accompanied the French ambassador to Constantinople and Greece, where he studied antiquities. Many trips lead him all over Europe. He devoted much of his time to art, and the study and collection of antiquities. The Comte de Caylus became an active member of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and of the Académie des Inscriptions. He was one of the first to consider archaeology as a science and had a considerable influence on Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the theorist of neoclassicism, who acknowledged his debt to him.[4]

The Birth of Archaeology

Probably the most important among the Comte de Caylus’ works is the profusely illustrated Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises (Collection of Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, Roman and Gallic antiquities, 1752-1765). The last and seventh volume was published posthumously in 1767. This book presents the objects and ancient monuments, totalling 2890, that form the core of its collection. It was mined by the designers of Neoclassical arts for the rest of the century. However, there are no less than 400 objects that do not belong to it. He thus published a large number of objects from the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum, despite the prohibitions of the King of the Two Sicilies. These bans concerned both the trade in Campania’s antiquities and their dissemination through drawing and engraving. His Numismata Aurea Imperatorum Romanorum, treats only the gold coinage of the Roman emperors, those worthy of collection by a grand seigneur. Caylus’ concentration on the object itself marked a step towards modern connoisseurship. In his Mémoire on the method of encaustic painting, the ancient technique of painting with wax as a medium mentioned by Pliny the Elder, he claimed to have rediscovered the method.[6] However, Diderot maintained that the proper method had been found by J.-B. Bachelier.[5]

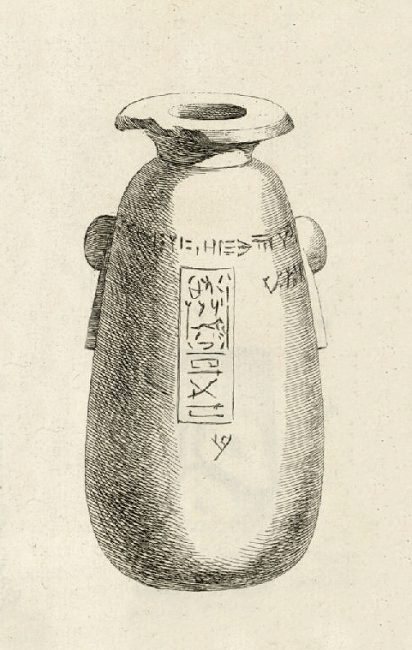

The “Caylus vase” in the name of Xerxes I, was key in the decipherment of cuneiform. Now in the Cabinet des Médailles.

Documenting the Findings

Caylus is known widely for his etching works and he copied many paintings of the great masters. Caylus caused engravings to be made, at his own expense, of Bartoli’s copies from ancient pictures and published Nouveaux sujets de peinture et de sculpture (1755) and Tableaux tirés de l’Iliade, de l’Odyssée, et de l’Enéide. Caylus also encouraged other artists and befriended the connoisseur and collector of prints and drawings Pierre-Jean Mariette. The Prix Caylus art prize, founded on his initiative in 1759 and named after him, was financed by a foundation from his own assets. It was awarded annually until 1968 as part of the concours de la tête d’expression competition at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He encouraged artists whose reputations were still in the making, and befriended the connoisseur and collector of prints and drawings Pierre-Jean Mariette when Mariette was only twenty-two, but his patronage was somewhat capricious. Diderot expressed this fact in an epigram in his Salon of 1765: “Death has delivered us from the cruelest of connoisseurs.“

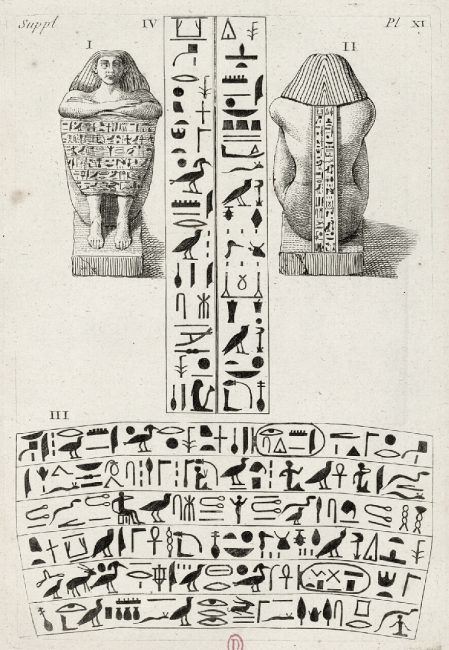

Transcription of hieroglyphs on an Egyptian statue by Count Caylus, 1767

The other Side of Caylus

Caylus had quite another side to his character. He had a thorough acquaintance with the gayest and most disreputable sides of Parisian life, and left a number of more or less witty stories dealing with it. These were collected (Amsterdam, 1787) as his Œuvres badines complètes. The best of them is the Histoire de M. Guillaume, cocher (c. 1730). His Contes, hovering between French fairy tales and oriental fantasies, between conventional charm and moral satire, have been collected and were published in 2005.

Anne Comte de Caylus died on September 5, 1765, aged 72.

Highlights: Forbidden Archaeology | Michael Cremo | Talks at Google [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Caylus, Anne Claude de Lévis“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 590.

- [2] The Comte de Caylus at the German Digital Library

- [3] The Comte de Caylus at Metmuseum

- [4] The Prophet of Modern Archeology – Joachim Winckelmann, SciHi Blog

- [5] Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, SciHi Blog

- [6] Pliny the Elder and the Destruction of Pompeii, SciHi Blog

- [7] Recueil d’antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines (7 volumes, 1752-1767)

- [8] Anna Comte de Caylus at Wikidata

- [9] Highlights: Forbidden Archaeology | Michael Cremo | Talks at Google, Talks at Google @ youtube

- [10] Perrin, Jean-François (2006). “Comte de Caylus, Contes“. Féeries. 3 (3): 382–387.

- [11] Timeline of French archaeologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata