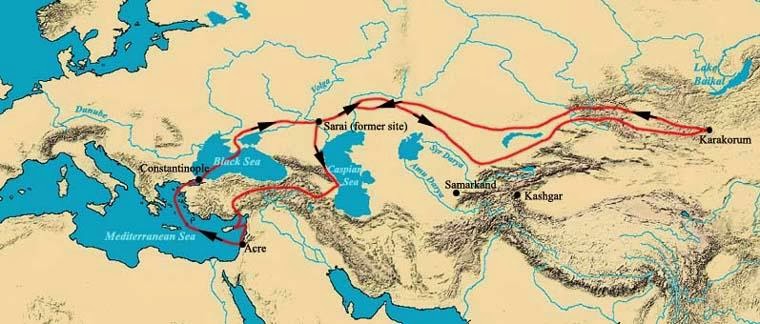

Voyage of William of Rubruck in 1253 – 1255

On January 4, 1254, Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer William of Rubruck was granted the privilege of an audience at the great Mongol Möngke Khan in his court in Karakorum. The Franciscan explorer was one of the first Europeans to study the culture of the Mongols.

William of Rubruck – Crusader and Missionary

The Flemish William of Rubruck, born in Rubrouck, Flanders, had joined the Franciscan Friars Minor at an early age, studied in Paris and in 1248 travelled to the Holy Land in the wake of King Louis IX and the seventh crusade, where he stayed for four years in Acre. In 1252, William was given the task to set out from Constantinople on a missionary journey to convert the Tatars to Christianity. Along with Bartolomeo da Cremona an attendant called Gosset, and an interpreter named in William’s report Homo Dei, he followed the route of the first journey of Friar Julian. Friar Julian was one of a group of Hungarian Dominican friars who, in 1235, left Hungary in order to find those Magyars who — according to the chronicles — remained in the eastern homeland. Already before William, other legations had been sent to the Mongols, for example Johannes de Plano Carpini in 1245 and André de Longjumeau in 1249. Wilhelm von Rubruk prepared for his journey with reports from traders and envoys, as with the travel report of André de Longjumeau, whom he also met in person.

The top half of this initial from a 14th century copy of the manuscript shows in the top half the report presented to Louis IX, and in the lower half William of Rubruck is depicted with a companion during the voyage

The Journey to Karakorum

William reached Sudak, a city located in the Ukraine and continued his travel with oxen. He crossed the river Don and met the ruler of the Kipchak Khanate, Sartaq Khan shortly after. From there, the traveler was sent to Batu Khan near the Volga, whom he reached about five weeks later. Batu turned out not to be very communicative but agreed to send him to the great Mongol Möngke Khan. The men faced a 9000km journey to meet him at Karakorum and he was given an audience on January 4, 1254. At first, they were received courteously, but William managed to record the extensive description of the city’s walls, markets and temples, and the separate quarters for Muslim and Chinese craftsmen among a surprisingly cosmopolitan population. William also described the town as a very religiously tolerant place, and the silver tree he described as part of Möngke Khan’s palace has become the symbol of Karakorum.

In religious, political and diplomatic terms, Wilhelm’s journey was a great disappointment because, contrary to Louis IX‘s expectations, the Grand Khan, with his tolerant attitude towards other religions and cultures, had no interest whatsoever in supporting Western Christianity in its struggle against Islam and in attempting to reconquer the Holy Land after the Kingdom of Jerusalem fell to the Muslims in the Battle of Hattin in 1187. With regard to the Pope’s expectations, while William and his fellow believer met Christians living within the sphere of influence of the Mongol Empire, a further missionary work of the Mongols did not seem promising to them.

Travelling Back

In the spring of 1255 William of Rubruk left Karakorum, returned to Cyprus in 1255, where he did not meet the French king due to his previous departure, and then arrived in Tripoli near Beirut on 15 August 1255. There his superiors did not let him travel on to his principals in Rome or France, but entrusted him with the task of a lecturer of theology in Acre. In Acre he dictated his travelogueItinerarium fratris Willielmi de Rubruquis de ordine fratrum Minorum, Galli, Anno gratia 1253 ad partes Orientales in the form of a letter to the French king and had it delivered to him by Gosset, one of his companions. His descriptions of the Mongolian geography, religion, and culture were the most precise, any European brought back home. This work counts as one of the greatest masterpieces of medieval geographical literature and is often compared to that of Marco Polo.[6]

In research he is considered to be the first European description which essentially contains reliable information from the Mongol Empire. Around 1257 Wilhelm was again in Paris, further dates of his life are not known.

Dolors Folch, The Rubruck mission (EDC2_3.1.2), [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] William of Rubruck’s Account of the Mongols, Silk Road Seattle, University of Washington. From the 1900 Rockhill translation.

- [2] (In German) Marina Münkler: Erfahrung des Fremden. Die Beschreibung Ostasiens in den Augenzeugenberichten des 13. und 14. Jahrhunderts, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2000

- [3] Rubruck Museum

- [4] William of Rubruck at Wikidata

- [5] “William Rubruck” from the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- [6] Marco Polo – the great Traveler and Merchant, SciHi Blog

- [7] Wilhelmus Rubruquensis: Itinerarium ad partes orientales. In: Anastasius van den Wyngaert (Hrsg.): Sinica Franciscana. Band 1: Itinera et relationes Fratrum Minorum saeculi XIII et XIV. Apud Collegium S. Bonaventurae, Firenze 1929, S. 164–332.

- [8] Dolors Folch, The Rubruck mission (EDC2_3.1.2), Mooc: The european discovery China. WEEK: Marcp Polo’s China. ACTIVITY: The first european travellers, Canal Mooc UPF @ youtube

- [9] Timeline of medieval explorers, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #26 | Whewell's Ghost