William Gilbert (1544-1603)

On May 24, 1544, English physician, physicist and natural philosopher William Gilbert was born. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book De Magnete (1600), and is credited as one of the originators of the term “electricity“. He is regarded by some as the father of electrical engineering or electricity and magnetism.

“Lucid gems are made of water; just as Crystal, which has been concreted from clear water, not always by a very great cold, as some used to judge, and by very hard frost, but sometimes by a less severe one, the nature of the soil fashioning it, the humour or juices being shut up in definite cavities, in the way in which spars are produced in mines.”

– William Gilbert, De Magnete, English translation by Silvanus Phillips Thompson, 1900

Career as a Physician

William Gilbert came from a middle-class family, his father was a lawyer (recorder) and citizen of Colchester. William Gilbert was the oldest of the five children from his first marriage (his father married twice). Gilbert studied from 1558 at St John’s College in Cambridge with the Bachelor’s degree (A.B.) in 1561 and the Magister artium in 1564 and was awarded a doctorate in medicine in 1569 (M.D.), after which he became a Senior Fellow of his College. He became 1558 Pensioner at College, 1561 Fellow of the Mr. Symon´s Foundation, 1565/66 Mathematical Examinor and 1569 and 1570 Senior Bursar. He may have gone abroad after completing his medical studies at Cambridge, but there is no precise proof of this. In the mid-1570s he settled as a doctor in London. In 1577 he received a coat of arms letter. He became (before 1581) a member of the Royal College of Physicians and was around 1581 one of the most respected doctors in London with many high-ranking patients.

Court Physician

In 1588 he was one of the four doctors at the College who, on behalf of the government, cared for the health of the Royal Navy. In 1600 he became President of the Royal College of Physicians, having held official positions there since 1582 and collaborated on their Pharmacopeia. In 1600 he received the post of Court Physician from Queen Elizabeth I,[4] after her death at the Court of King James I. He lived in Wingfield House in St Peters Hill in London, probably a heir to his stepmother, and had his laboratory there. He may have died of the plague and left his instruments and books to the Royal College of Physicians. The estate, his library and his house were destroyed like the Royal College by the Great Fire of London in 1666.[6]

Research in Magnetism

To his most important works belongs De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure (On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on the Great Magnet the Earth). It is the first summary treatment of magnetism since Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt in the 13th century. In this work, published in 1600, Gilbert described many of his experiments with his model Earth called the “Terrella” (Latin “small earth“). From these experiments, he concluded that the Earth was itself magnetic and that this was the reason compasses point north. While some of his contemporaries thought that the tip of the compass needle was attracted to the polar star, he showed convincingly that the earth as a whole must be regarded as a single magnet with two poles. He also concluded this from the inclination of the magnetic needles discovered by Georg Hartmann and published by Robert Norman (The New Attractive 1581). However, the decisive factor was his own experiments with a spherical magnet. According to his imagination, magnetism was the “soul” of the earth and was implanted in it by God. He assigned each magnet a sphere of influence, a precursor of the field concept. He suggested that seafarers should record deviations from the direction of the magnetic needle to the North Pole and gave instructions for this.

Relating the Cosmos to the Power of the Magnet

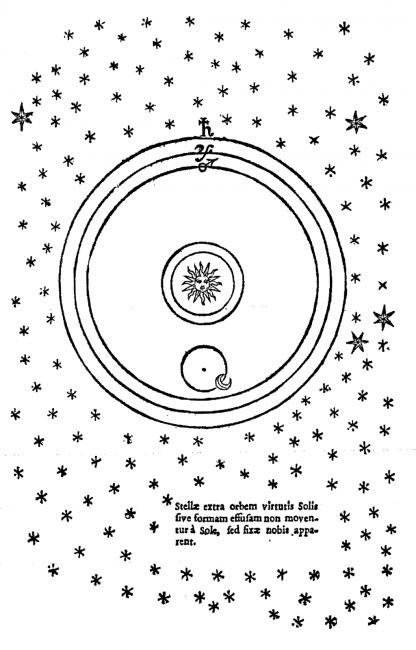

Like Peregrinus, Gilbert believed that rotation was one of the magnetic movements and that a balanced spherical magnet would rotate. In the sixth book of his De Magnete, in which he transferred his magnetic philosophy to the cosmos, he argued that the daily rotation of the earth was due to magnetism. He rejected the idea of a fixed star sphere with a fixed distance. Tides and the precession of the equinoxes he also tried to attribute to magnetism, but the arguments were weak and the sixth book of his major work was therefore criticized by Francis Bacon and others.[5] It is further assumed that Gilbert was the first to argue that the centre of the Earth was iron, and he considered an important and related property of magnets was that they can be cut, each forming a new magnet with north and south poles. In the work, Gilbert further argued that the “fixed” stars are at remote variable distances rather than fixed to an imaginary sphere.

Diagram appearing on p202 of De Mundo, showing Gilbert’s conception of the solar system. He rejected the idea of the “sphere of the stars” as shown clearly in De Magneto, published in 1600.

In Physiologia he denies the existence of Aristotle’s four elements and replaces them with a single one, Earth. Its characteristic feature was magnetism. Parts of the earth without magnetic property are degenerate forms of the earth and most liquids Effluvia of this basic element earth. According to Gilbert, the other celestial bodies were similar in structure, even if he formulated this explicitly only for the moon. According to Gilbert this was a reduced earth with seas (the brighter areas) and continents. The Sun, like the stars, was a light-emitting body, unlike the five planets that orbited the Sun and were driven by it as a driving magnetic force on its orbits. The Earth he took from this drive by the Sun, although it was like the other planets in its magnetic sphere of influence. He discussed the ideas of Nicolaus Copernicus [7] and Giordano Bruno, but did not explicitly advocate or oppose the heliocentric worldview. How

Electricity

On this day, it is assumed that the term electricity was first used by Sir Thomas Browne in 1646, probably derived from Gilbert’s 1600 New Latin electricus, meaning “like amber”. He recognized that friction with these objects removed a so-called “effluvium”, which would cause the attraction effect in returning to the object, though he did not realize that this substance was universal to all materials. In his book, he also studied static electricity using amber; amber is called elektron in Greek, so Gilbert decided to call its effect the electric force. He invented the first electrical measuring instrument, the electroscope, in the form of a pivoted needle he called the versorium. In his book, Gilbert also studied static electricity using amber. Since amber is called elektron in Greek, Gilbert decided to call its effect the electric force. Gilbert is credited with inventing the first electrical measuring instrument, the electroscope, in the form of a pivoted needle he called the versorium. William Gilbert also pointed out that electricity and magnetism were not the same thing. Hans Christian Ørsted and James Clerk Maxwell later correctly showed that both effects were aspects of one single force: electromagnetism.

Gilbert’s Writings

A collection of Gilbert’s unfinished writings was collected in 1651 by his half-brother William Gilbert of Melford under the title De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova (New Philosophy about our sublunar world) and were known for example to Francis Bacon and Thomas Harriot. They were published in Amsterdam in 1651. It was unfinished and the first part (Physiologiae nova contra Aristotelem, probably 1590s) continued the cosmological ideas from the last book of De magnete and presupposed its terms. The second part Nova meterorologia contra Aristotelem probably originated as an independent work and deals with comets, the Milky Way, rainbows, clouds, wind, tides and the sea, origin of rivers and others. However, the legacy of his writings was far less influential than his main work, which proved to be groundbreaking for the scientific research of future generations.

Earth’s Magnetic Field, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] William Gilbert at NASA

- [2] The Natural Philosophy of William Gilbert and His Predecessors

- [3] William Gilbert at BBC

- [4] The Virgin Queen – Elizabeth I., SciHi Blog

- [5] Sir Francis Bacon and the Scientific Method, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Great Fire of London, SciHi Blog

- [7] Nikolaus Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model, SciHi Blog

- [8] Works by or about William Gilbert at Wikisource

- [9] Works by or about William Gilbert at Internet Archive

- [10] Who created the first scientific map of the moon? – I expect better of the British Library, The Renaissance Mathematicus, March 20, 2019

- [11] Earth’s Magnetic Field, Mindset @ youtube

- [12] Zilsel, Edgar (1941). “The Origin of William Gilbert’s Scientific Method” (PDF). Journal of the History of Ideas. 2 (1): 1–32.

- [13] Chapman, Sydney (29 July 1944). “William Gilbert and the Science of his Time”. Nature. 154 (3900): 132–136.

- [14] Timeline of “Magneticians”, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #41 | Whewell's Ghost