Sir Thomas Bodley (1544-1613)

On March 2, 1544, English diplomat and scholar Sir Thomas Bodley was born. His greatest achievement was the re-founding of the library at Oxford that was named in his honor. Moreover, he established new ideas and practices library of which also modern libraries still benefit today.

The Roots of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library is the main research library of the University of Oxford and it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. Known to Oxford scholars as “Bodley” or simply “the Bod”, it is one of six legal deposit libraries for works published in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland with currently over 11 million items. Whilst the Bodleian Library, named after its founder Thomas Bodley has a continuous history dating back to 1602, its roots date back even further into the fourteenth century, when the first purpose-built library known to have existed in Oxford was founded by Thomas Cobham, Bishop of Worcester. This small collection of chained books continued to grow steadily, but when, in 1437 Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and the youngest son of Henry IV of England, donated a great collection of manuscripts, the space was deemed insufficient and a larger building was required. A suitable room was finally built above the Divinity School, and completed in 1488. By the end of the sixteenth century the library went through a period of decline starting with the Reformation of the 1550s, where the library had been stripped and abandoned. It was not until 1598 that the library began to thrive once more, when Thomas Bodley wrote to the Vice Chancellor of the University offering to support the development of the library:

“where there hath bin hertofore a publike library in Oxford: which you know is apparent by the rome it self remayning, and by your statute records I will take the charge and cost upon me, to reduce it again to his former use.”[1]

Sir Thomas Bodley’s Donation

Duke Humfrey’s Library was refitted, and Bodley donated a number of his own books to furnish it. The library was formally re-opened on November 8, 1602 under the name “Bodleian Library” (officially Bodley’s Library). In 1610, Bodley made an agreement with the Stationers’ Company in London, in which

“the Company agreed to send to the Library a copy of every book entered in their Register on condition that the books thus given might be borrowed if needed for reprinting, and that the books given to the Library by others might be examined, collated and copied by the Company.”[2]

A rather successful idea. By 1620, 16,000 items were in the Bodleian’s collection. According to a 1867 count, the library contained around 350,000 printed books and 25,000 manuscripts; in 2000 it already contained 6.75 million books, 178,000 manuscripts and 6,500 incunabula over 173 kilometres of books.

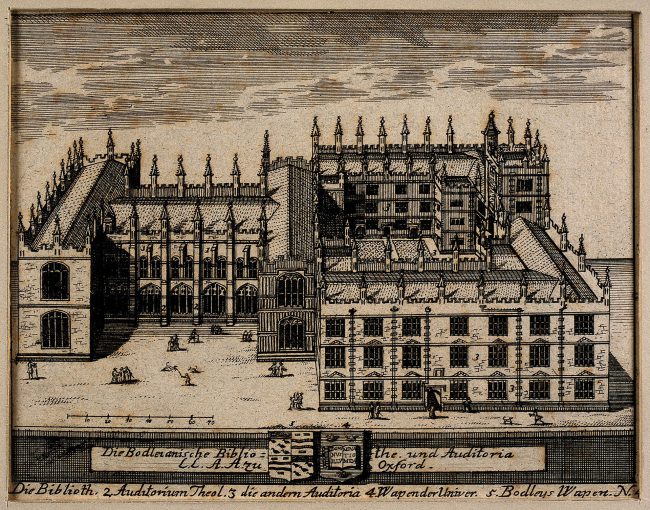

Ancient engraving of the Bodleian Library, showing below the arms of Bodley quartering the canting arms of Hone

Thomas Bodley – Early Life

Thomas Bodley was born at Exeter to John Bodley, a Protestant merchant who went to live abroad rather than stay in England under the Catholic regime of Queen Mary. The family sought refuge in Germany, staying briefly in the towns of Wesel and Frankfurt before eventually settling in Geneva. There, Thomas had the opportunity to study at John Calvin‘s newly erected Académie and learned Greek and Hebrew, which should remain enduring passions throughout his life. After the accession of Queen Elizabeth I [5] in 1558 to the English throne, the family returned to England, and Bodley entered Magdalen College, Oxford. In 1563 he took his B.A. degree, and was shortly thereafter, in 1564, admitted as a Fellow to Merton College, where he began lecturing Greek. Leaving Oxford in 1576 with a license to study abroad including a grant from his college, he visited France, Italy, and Germany. On his return he was appointed gentleman-usher to Queen Elizabeth and he became member of the Parliament. Starting in 1585, Bodley was dispatched on several critical diplomatic missions, which demanded great diplomatic skill. Moreover, the essential difficulties of his missions were complicated by the intrigues of the queen’s ministers at home, and Bodley repeatedly asked to be recalled.

Ex libris stamp of Bodleian Library, circa. 1830.

The Inspiration to Restore the Old Library

He was finally permitted to return to England in 1596 and retired from public life to return to Oxford. As he had married Ann Ball, a rich widow, in 1587 he had had to resign his fellowship at Merton, but he still had many friends there and in spring 1598, the college gave a dinner in his honour, which is speculated that this might have been the inspiration to restore the old Duke Humfrey’s library. Once his proposal was accepted Thomas Bodley spent the rest of his life devoted to the library project.

The Benefactors’ Book

One important idea that Bodley implemented with his library was the creation of a “Benefactors’ Book” in 1602, which was bound and put on display in the library in 1604. While he did have funding through the wealth of his wife and the inheritance he received from his father, Bodley still needed gifts from his affluent friends and colleagues to build his library collection. Bodley recognized that having the contributor’s name on permanent display was rather inspiring – and still is today. Sir Thomas Bodley, he was knighted in 1604. He died on January 28, 1613 at Oxford, and was buried in the choir of Merton College chapel, where a black and white marble monument was erected in his honour.

It takes an Oath…

Before being granted access to the Bodleian Library, new readers are required to agree to a formal declaration. This declaration was traditionally an oral oath, but is now usually made by signing a letter to a similar effect. Ceremonies in which readers recite the declaration are still performed for those who wish to take them; these occur primarily at the start of the University’s Michaelmas term. The English text of the declaration is as follows:

I hereby undertake not to remove from the Library, nor to mark, deface, or injure in any way, any volume, document or other object belonging to it or in its custody; not to bring into the Library, or kindle therein, any fire or flame, and not to smoke in the Library; and I promise to obey all rules of the Library.

Friends of the Bodleian Annual Lecture 2020 with Laura Wade and Samuel West, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Philip, Ian: The Bodleian Library in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983.

- [2] Nicoll, Allardyce, ed. Shakespeare Survey Vol. 4: An Annual Survey of Shakespearean Study & Production. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

- [3] The official Website of the Bodleian Library

- [4] Sir Thomas Bodley at Wikidata

- [5] The Virgin Queen – Elizabeth I., SciHi Blog, September 7, 2013.

- [6] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- [7] Works by or about Thomas Bodley at Internet Archive

- [8] Friends of the Bodleian Annual Lecture 2020 with Laura Wade and Samuel West, Bodleian Libraries @ youtube

- [9] Timeline with Librarians of the Bodleian Library, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #29 | Whewell's Ghost