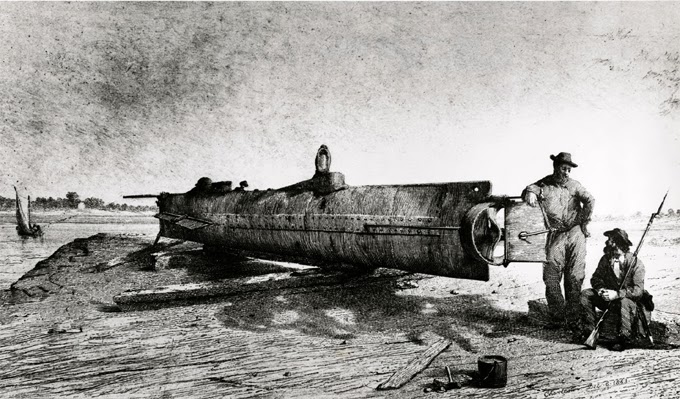

Drawing of the H. L. Hunley. Based on a photograph taken in 1863

On the night of February 17, 1864, the submarine H.L.Hunley of the American Confederate Army sank the steamship USS Housatonic with a torpedo and became the very first submarine to attack and sink an enemy vessel. The Hunley was lost at some point following her successful attack and all crewmen were lost. Although the Hunley only played a small part in the American Civil War, it was a large role in the history of naval warfare and demonstrated both the advantages and the dangers of undersea warfare.

Horace Lawson Hunley and the Pioneer

In the time of the American Civil War, the three inventors Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson first built a small submarine named Pioneer in New Orleans, Louisiana. Pioneer was tested in February 1862 in the Mississippi River and was later towed to Lake Pontchartrain for additional trials. But the Union advance towards New Orleans caused the men to abandon development and scuttle Pioneer the following month. The three inventors moved to Mobile and joined with machinists Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons. They soon began development of a second submarine, American Diver. Supported by the Confederate States Army the men experimented with electromagnetic and steam propulsion for the new submarine, before falling back on a simpler hand-cranked propulsion system, which in the end proved too slow to be practical. One attempted attack on the Union blockade was made in February 1863 but was unsuccessful. The submarine sank in the mouth of Mobile Bay during a storm later the same month and was not recovered.

The Construction of the Hunley

Construction of Hunley began soon after the loss of American Diver in Mobile, Alabama. Hunley, nearly 12 m long was launched in July 1863. She was then shipped by rail on August 12, 1863 to Charleston, South Carolina. It was designed for a crew of eight: seven to turn the hand-cranked propeller and one to steer and direct the boat. Each end was equipped with ballast tanks that could be flooded by valves or pumped dry by hand pumps. Extra ballast was added through the use of iron weights bolted to the underside of the hull. In the event the submarine needed additional buoyancy to rise in an emergency, the iron weight could be removed by unscrewing the heads of the bolts from inside the vessel. It was equipped with two watertight hatches, one forward and one aft, atop two short conning towers equipped with small portholes and slender, triangular cutwaters.

Dangerous Testing

The military seized the vessel from its private builders and owners shortly after its arrival in Charleston, turning it over to the Confederate Army. Hunley would operate as a Confederate Army vessel from this point forward, although Horace Hunley and his partners remained involved in the submarine’s further testing and operating. Hunley (then called Fish Boat) sank on August 29, 1863, for the first time during a training exercise, killing five members of her crew. She sank again on October 15, 1863, killing all eight of her second crew, including inventor Horace Hunley himself, who was aboard at the time, even though he was not enlisted in the Confederate armed forces. Both times Hunley was raised and returned to service.

The Attack on the USS Housatonic

Hunley was originally intended to attack by means of a floating explosive charge with a contact fuse (a torpedo in Civil War terminology) towed behind it at the end of a long rope. Hunley would approach an enemy vessel, dive under it, and surface beyond. As it continued to move away from the target, the torpedo would be pulled against the side of the target and explode. The floating explosive charge was replaced with a spar torpedo, a copper cylinder containing 41kg of explosives attached to a 7m-long wooden spar. The spar was mounted on Hunley’s bow and was designed to be used when the submarine was 2m or more below the surface. The spar torpedo had a barbed point, and would be stuck in the target vessel’s side by ramming. On the night of February 17, 1864, the Hunley made her first and only attack against a live target. The vessel was the USS Housatonic. Housatonic, a 1240-ton steam-powered sloop-of-war with 12 large cannons, was stationed at the entrance to Charleston, South Carolina harbor.

Was it Worth While?

In an effort to break the naval blockade of the city, Lieutenant George E. Dixon and a crew of seven volunteers attacked Housatonic, successfully embedding the barbed spar torpedo into her hull. The torpedo was detonated as the submarine backed away, sending Housatonic and five of her crew to the bottom in five minutes. After the attack, the H.L. Hunley failed to return to her base. What really happened, remains unclear. Dixon would have taken his submarine underwater to attempt to return to Sullivan’s Island. Hunley sank, killing all eight of her third crew. This time, the innovative ship was lost. The finders of the wreck suggested that she was unintentionally rammed by the USS Canandaigua when that warship was going to the aid of the crew of the Housatonic. Years later, when the area around the wreck of the Housatonic was surveyed, the sunken Hunley was finally found on the seaward side of the sloop’s wreck, where no one before had ever considered looking. This later indicated that the ocean current was going out following the attack on the Housatonic, taking Hunley with it to where its wreck was eventually found and recovered more than 130 years later in August 8, 2000. Currently, H.L. Hunley is undergoing archaeological study and conservation treatment at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center.

Rachel Lance, The Fate of the Submarine H.L. Hunley, [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] H.L. Hunley Webpage

- [2] H.L. Hunley at Britannica Online

- [3] The H. L. Hunley at Wikidata

- [4] Timeline of Submarine Pioneers, via DBpedia and Wikidata

- [5] Rachel Lance, The Fate of the Submarine H.L. Hunley, US National Archives @ youtube

- [6] “H.L. Hunley Fact Sheet”. The Hunley.

- [7] Yasko, Karel (February 1976). “H. L. Hunley (Submarine)”. National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form – Inventory. National Park Service.

- [8] Robert F. Burgess (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea: A History of Subs and Submersibles. New York: McGraw Hill.

- [9] Image grid with submarines, via Wikidata

Mighty interesting.

Hi Tor,

Thanks for the comment and enjoy our blogposts and videos!

Best,

Harald

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #32 | Whewell's Ghost