Sandro Botticelli (1445 – 1510)

On March 1, 1445, Sandro Botticelli was born, one of the most important Italian painters and draftsmen of the early Renaissance. Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until he was rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites in the 19th century, who stimulated a reappraisal of his work. Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is probably one of the most popular renaissance paintings in the world.

Sandro Botticelli – Early Life

One of the first sources about Botticelli’s life comes from the biographical collection of Giorgio Vasari [1] from 1550 (new edition: 1568), which, however, is doubted in its truthfulness. According to this, “Botticelli” – the nickname (from botticello “little barrel”) comes from his brother Giovanni – was born in the Florentine working-class district of Ognissanti as the youngest son of the tanner Mariano di Vanni Filipepi. He remained attached to this city all his life. Vasari attested to his lack of diligence at school; he was always restless there and was never satisfied with any lessons. His father apprenticed him to a goldsmith; this was probably the basis for a penchant for extravagant jewelry in his later portraits of ladies.

From 1464 he became a student for three years in the Prato workshop of Fra Filippo Lippi (1406-1469), the most famous painter in the city at the time. Florence remained his intellectual home throughout his life, where he received strong artistic stimuli from the humanism particularly promoted in Florentine noble circles.

Between 1465 and 1470 Botticelli produced a series of Madonna paintings, including the Madonna with Child and Two Angels, produced between 1468 and 1469. In these early works the influences of his teacher Lippi are clearly evident, but also the more robust style of the two leading painters in Florence at the time, Antonio Pollaiuolo and Andrea del Verrocchio, in whose school Botticelli was probably.

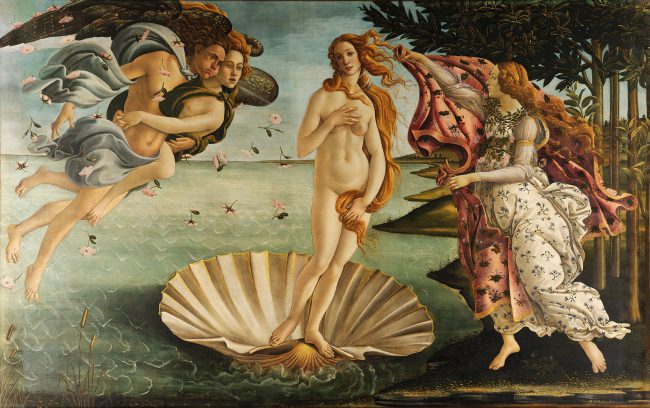

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485

Work in his own Workshop

In 1470 Botticelli opened his own workshop. In the same year, he was commissioned by Tommaso Soderini to create an image of Fortitude (Fortitudo) in the series of the seven virtues for the guild court Tribunale della Mercanzia. Repeated contacts with the Medici and the special patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici granted him political protection, secured him public commissions for the next 20 years – including by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici – and provided ideal conditions for the creation of numerous masterpieces. Botticelli was known and loved as a portrait painter in his native city. In the aftermath of the Pazzi Conspiracy, Botticelli captured the hanged assassins in a public disgrace painting. The portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici, who was murdered in the assassination, was produced in several serially produced versions for Florentine patrons, who could thus testify to their loyalty to the Medici family. From the 1470s Filippino Lippi also worked in his workshop.

Sandro Botticelli, The Spring (La Primavera), c. 1478/82

Mature Masterpieces

The close connection with the humanist thought of the time and the creative imagination of the artist are shown by his more mature masterpieces after 1475, especially his allegorical representations The Spring, in which the awakening of nature is embodied by flower-crowned girls in a paradisiacal landscape, and The Birth of Venus, in which the goddess of love, born from the foam of the sea, floats to the coast in a shell. The latter represented the first nearly life-size painted female nude since antiquity.

Sandro Botticelli, Idealized Portrait of a Lady (Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Nymph), c. 1480

Like these works, the painter’s devotional paintings from this period (including The Adoration of the Magi and The Coronation of Mary) combine this contemporary thought with older pictorial ideas modeled on the Gothic. The overly slender figures and limbs of his female figures, their pale, melancholy faces flowing with rich golden hair, show in nervous delicacy these echoes of Gothic, also in the balance of the composition of the picture. This recurring female facial expression typical of Botticelli in Madonna, portrait and allegorical representations, as realized in the “Female Ideal Portrait“, has been repeatedly associated by some art historians with the features of Simonetta Vespucci, who died young in 1476.

Between 1481 and 1482 Botticelli was summoned to Rome by Pope Sixtus IV. Working in a team with Perugino, Ghirlandaio and Signorelli, among others, he decorated the newly built Sistine Chapel with large murals depicting events from the life of Jesus and Moses, and with portraits of earlier popes.

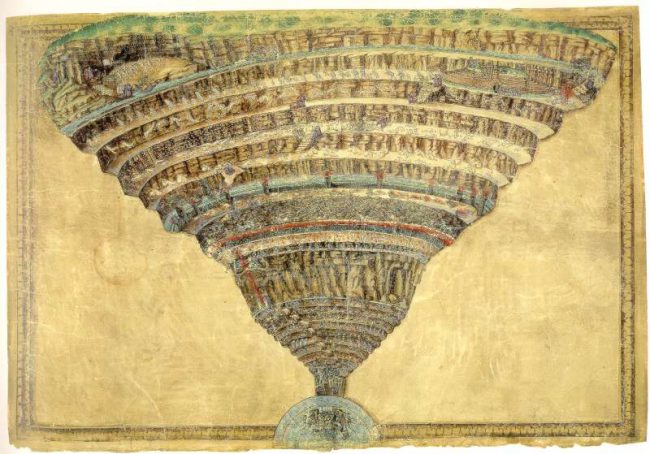

Sandro Botticelli, Chart of Dante’s Hell, created after Dante’s Divine Comedy. c. 1485

Later Years

The death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in 1492 meant for the time being the end of the brilliant epoch of Florentine art and the beginning of social and ecclesiastical unrest, especially after the expulsion of the Medici in 1494, when Savonarola established his divine state in Florence until his execution in 1498.[2] Under his influence, as Vasari relates in his Vite, Botticelli devoted himself only to spiritual subjects and completely neglected painting. That Botticelli, like his brother Simone, was one of Savonarola’s followers is, however, very doubtful, as the new Botticelli research has worked out. Neither did Botticelli sign the petition to the Pope for a pardon of the Dominican, nor did Botticelli’s workshop stop working. In contrast to the strong brightness and elaborate decoration of his earlier paintings, however, Botticelli’s figures were now clad in plain, simple robes, and darker hues predominated. His 94 pen-and-ink drawings of Dante Alighieri‘s Divine Comedy, created during this period, became famous.[3]

The End

After 1500, Botticelli was unable to paint himself, possibly due to a disability, while his workshop continued to work. Vasari describes the artist in his old age as an impoverished man who hobbled around town on crutches. After his death on May 17, 1510, Botticelli was buried in the cemetery of the Ognissanti church in that Florentine neighborhood where he had spent most of his life.

Frederick Ilchman, Botticelli: The Curator’s View, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Giorgio Vasari and his Foundations of Art-Historical Writing, SciHi Blog

- [2] Girolamo Savonarola’s Bonfire of Vanities, SciHi Blog

- [3] Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [4] Hudson, Mark, “Before Bowie, there was Botticelli” , The Daily Telegraph, 14 February 2016

- [5] Lightbown, Ronald, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 1989, Thames & Hudson

- [6] World of Dante Botticelli’s Dante illustrations and interactive version in the Chart of Hell

- [7] Colvin, Sidney (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- [8] Sandro Botticelli at Wikidata

- [9] Frederick Ilchman, Botticelli: The Curator’s View, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston @ youtube

- [10] Timeline for Sandro Botticelli, via Wikidata