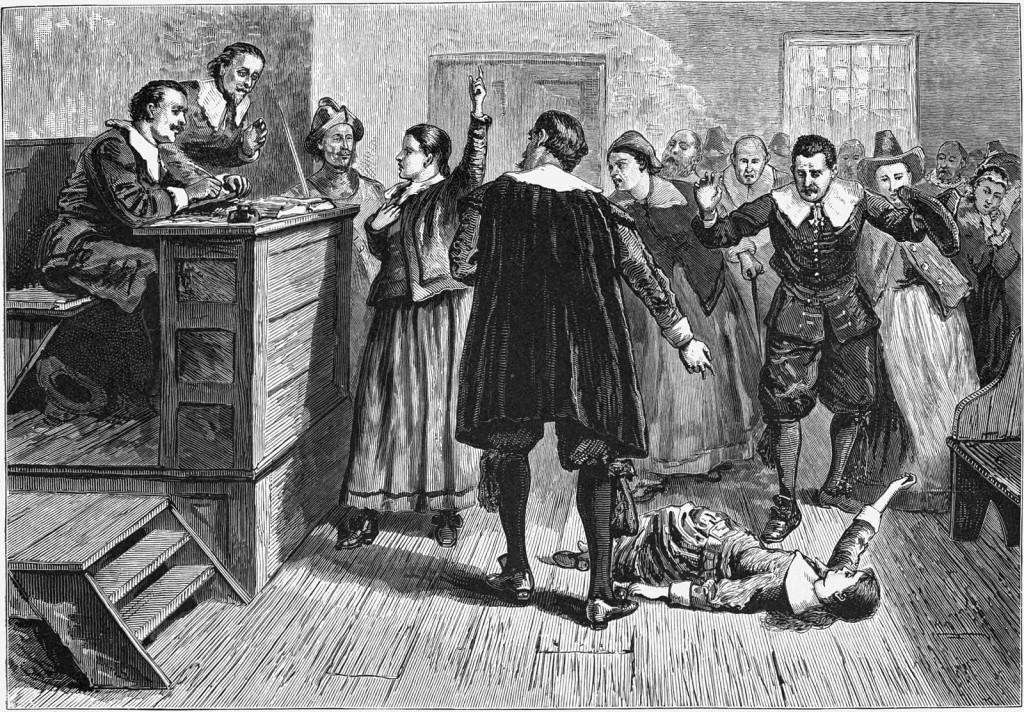

Witchcraft at Salem Village, engraving (1876)

On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey, who was accused of witchcraft along with his wife Martha Corey during the Salem Witch Trials, was subjected to pressing in an effort to force him to plead, but instead he died after two days of torture. The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. The trials resulted in the executions of twenty people, most of them women.

What Happened

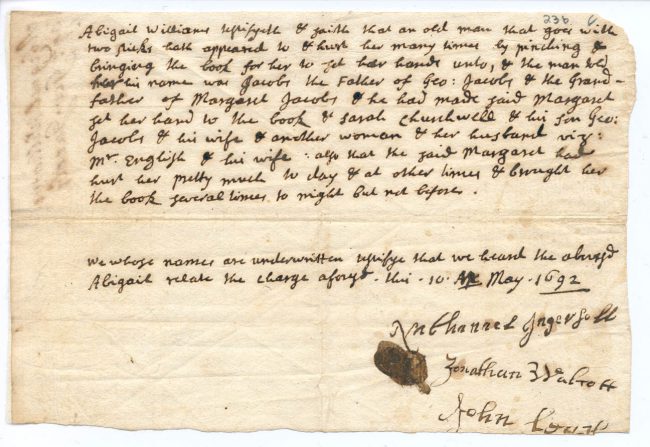

In February 1692, a 9-year old girl named Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams started to show a strange behavior, which the minister of the nearby town described as “beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect”. This meant throwing things in the room, making sounds and crawling under furniture. Apparently, other women in the village began to show the same ‘symptoms’. At first, three people were accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting the girls: Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. The first was a homeless woman and during her trial she was accused of rejecting Puritan ideals of self-control and discipline. The second, Sarah Osborne, rarely attended church meetings and was accused of witchcraft because the Puritans believed that Osborne had her own self-interests in mind following her remarriage to an indentured servant. Tituba, a black or Indian slave, likely became a target because of her ethnic differences from most of the other villagers. The village community, threatened by indigenous tribes and left without formal government after the abrogation of the Bay Colony Treaty of 1684 and the 1689 Rebellion, believed the accusations. Brought before the local magistrates on the complaint of witchcraft, they were interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692, then sent to jail.

The deposition of Abigail Williams v. George Jacobs, Sr.

Accusations

More women were accused of witchcraft in March including the 4-year old Dorothy Good. Also, warrants were issued later for 36 more people, with examinations continuing to take place in Salem Village. During the months of June and July found many of these women guilty and five women were executed by hanging on July 19, 1692 and even more were executed in August. Then, in September, grand juries indicted eighteen more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at arraignment, and was subjected to peine forte et dure, a form of torture in which the subject is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make him enter a plea. Four pleaded guilty and eleven others were tried and found guilty.

Effect of the Trials

During the Salem witch trials, crops were not harvested and cattle were neglected. Sawmills stood idle because either the owners were missing, their workers were arrested, or they attended jails and trials. Some defendants fled. Trade came to a virtual standstill, while the threat of Indians in the West remained. Under the leadership of Increase Mather, Boston clergymen filed a plea on October 3, 1692, entitled “Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits.” In it, Mather stated that it was better for ten suspected witches to escape than for one innocent person to be convicted. The witch trials ended in January 1693, and the last of those arrested were released in the spring of the following year. The Salem Witch Trials resulted in the executions of 20 people and became one of the most infamous trials in history.

Rehabilitation

A general amnesty was granted in 1711 for most of those convicted in the Salem witch trials. In 1957, Ann Pudeator, who was hanged as a witch, was declared innocent. On November 5, 2001, the Governor of Massachusetts signed the declaration of innocence for the final five women.[4] In August 2021, Elizabeth Johnson Jr. who was pardoned in 1693 was also fully rehabilitated at the behest of a school class.

Emerson “Ted” Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Witch Trials [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692

- [2] Chronology of the Salem Witch Trials

- [3] Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, by Charles Upham, 1867, Project Gutenberg

- [4] “Massachusetts Clears 5 From Salem Witch Trials”. The New York Times. November 2, 2001.

- [5] Burr, George Lincoln, ed. (1914). Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648–1706. C. Scribner’s Sons.

- [6] Bunn, Ivan; Geiss, Gilbert (1997), Trial of Witches: A Seventeenth-Century Witchcraft Prosecution, Routledge,

- [7] Roach, Marilynne K. (2002), The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, Cooper Square Pre

- [8] SalemWitchTrials.com Essays, biographies of the accused and afflicted, Salem Witch Trials website

- [9] The Salem Witchcraft Trials at Wikidata

- [10] Emerson “Ted” Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Witch Trials, Museum of Old Newbury @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of Witch Trials and related persons, via Wikidata and DBpedia