Rudolf Virchow (1821 – 1902)

On October 13, 1821, German doctor, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician, Rudolf Virchow was born. He is best known for his advancement of public health. Furthermore, he is also referred as “the father of modern pathology” because his work helped to discredit humorism, bringing more science to medicine. He is also considered one of the founders of social medicine.

“For if medicine is really to accomplish its great task, it must intervene in political and social life. It must point out the hindrances that impede the normal social functioning of vital processes, and effect their removal.”

– Rudolf Virchow, Pathologies of Power, 1849

Rudolf Virchow – Early Years

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow was born in Schivelbein, Province of Pomerania, as the only child of the trained businessman, from 1828 as an agricultural treasurer and later a 50 acres butcher’s master son Carl Christian Siegfried Virchow (1785-1864) and his wife Johanna Maria née Hesse (1785-1857) from Belgard. Rudolf Virchow was often ill as a child. From 1828 he went to the Schivelbein town school and also received foreign language instruction from clergymen. From May 1835 he attended the Gymnasium in Köslin, where he passed his school-leaving examination in the spring of 1839. Despite his financial circumstances did not allow him to study at a university, Rudolf Virchow studied medicine at the University of Berlin and received his doctorate on pathology in 1843.

First Research in Leukaemia

“The task of science is to stake out the limits of the knowable, and to center consciousness within them.”

– R. Virchow. Der Mensch (On Man). Berlin, 1849

Virchow then continued his military medical training and worked as an assistant to Robert Froriep in the Charité Prosektur. On 3 May 1845, he gave his first public speech on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Pépinière as a former whistling cock. In this speech (On the Need and Correctness of Medicine from a Mechanical Point of View), he described life, which is subject to general physical and chemical laws, essentially as the activity of the cell and also explained his ideas about the development of phlebitis, thereby causing considerable contradiction among the audience. In 1845 he described white blood in leukaemia, the name of which he coined from 1847 onwards (the terms thrombosis and embolism also go back to Virchow). He passed his state examination from autumn 1845 to spring 1846.

Working in Berlin

In May 1846 Virchow, who at the age of 24 was already giving private lectures, received the vacant position of the prosector at the Charité. After he had retired from military medical service at his own request, Virchow habilitated in November 1847, immediately became a private lecturer and, also in order to disseminate his views in the form of a journal, began publishing the Archive for Pathological Anatomy and Physiology and for Clinical Medicine with his friend Benno Reinhardt, which has appeared to this day in over 450 volumes, meanwhile as Virchow’s Archive. In 1848 Virchow was involved in the March Revolution by participating in the barricade construction, but also by his social analysis of the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia, where he was active until March 10, he surpassed himself with the Prussian government, whose politics he regarded as the cause of the bad hygienic and social conditions. Thus his position in Berlin became untenable and he finally lost his apartment as well as the position as prosector in March 1849. Several universities, including ETH Zurich, offered him a chair.

Professorship in Würzburg

Rudolf Virchow accepted the reputation of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg as successor of the late Bernhard Mohr in the winter semester 1849. On November 15, 1849 Virchow took over the chair of Pathological Anatomy as full professor. He began his work in Würzburg, where there was no independent pathological institute before Virchow, on 30 November and from 1 December 1849 he read General Pathology and Pathological Anatomy as well as History of Medicine. With regard to medical publications, Würzburg was Virchow’s most productive time. Among other things, he dealt with thromboses and cells. Numerous students from many countries came to the newly created Virchow Institute. One of his pupils was the zoologist Ernst Haeckel.[5] In order to investigate the phenomenon of cretinism, which was common in the villages of Franconia at the time, he examined numerous skulls of Lower Franconian deceased and published about it from 1851.

Every Cell Originates from a Cell

“Where a cell arises, a cell must have preceded it, just as the animal can arise only from the animal, the plant only from the plant.”

– Rudolf Virchow, 1859, as quoted in [11]

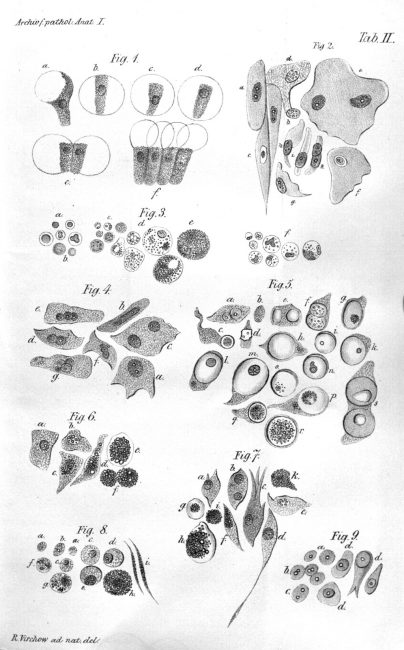

At the request of the Medical Faculty of Berlin University, Rudolf Virchow was appointed Professor of Pathology and Therapy in Berlin in 1856. In the same year he took over the newly created Ordinariat für Pathologie on the premises of the Charité as well as his old position as prosector at the Charité. Virchow also had his own institute building, the first pathological institute in Germany. In 1858, his book Die Cellularpathologie (Cellular Pathology) was published, based on physiological and pathological tissue theory. The theory presented in 20 lectures from February to April 1858 states that diseases are based on disorders of the body cells. He deduced this from his investigations, which were mainly carried out in Würzburg, and which showed that all (plant, animal and human) cells originate from cells and not, as previously assumed, from a misshapen primeval slime (blastem). The well-known principle of Virchow’s cell theory since 1855 has been Omnis cellula e cellula, translated as “Every cell [originates] from one cell“.

Illustration of Virchow’s cell theory, Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie (now known as “Virchow’s Archives”), 1847, first issue

The Cause of Thrombosis

The principle of the cause of thrombosis recognized by Virchow and the theory of cellular pathology were decisive for the replacement of the Krasen theory previously used in medicine, which attributes diseases to an uneven mixture of bodily fluids, and thus the humoral pathology existing since antiquity, which regarded harmful mixtures of bodily fluids as the cause of disease, by a modern, scientifically founded pathology and pathophysiology.

Virchow in his study at the Royal Charité in Berlin, 1895 ( Le Monde moderne)

Medical Malpractice

In 1870 Virchow coined the concept of medical malpractice as “violation of the recognized rules of the art of healing due to a lack of proper attention or caution“. In court practice, the concept of artificial defect concerns violations of generally recognized rules of medical science (Latin: Lege artis), i.e. “such oversights which as a rule are based on ignorance or inadequate knowledge, less on incompetence or even on mere inattention”. Virchow remained in Berlin for 46 years until his death. In the year 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, he organized hospital trains, with which he himself travelled to the front, and had barrack hospitals erected on the Tempelhofer Feld.

“The future is with the vegetarians.”

– Rudolf Virchow, quoted in [10]

The End

On his way to a meeting of the Gesellschaft für Erdkunde on the evening of January 4, 1902, he crashed while jumping off a tram in Leipziger Straße and broke his femoral neck. He did not recover from the protracted consequences of this accident despite an initially promising bathing and spa stay in May 1902 in the Bohemian town of Teplitz. Already on 11 August 1902 the Neue Preußische (Kreuz-)Zeitung[42] reported on his poor state of health. He died eight months after his accident on 5 September 1902 in Berlin at age 80.

Ted Schrecker, Rediscovering Virchow, revisiting Brecht: Health politics for a new Gilded Age, [9]

Selected Works by Rudolf Virchow:

- Mittheilungen über die in Oberschlesien herrschende Typhus-Epidemie (1848)

- Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre., his chief work (1859; English translation, 1860): The fourth edition of this work formed the first volume of Vorlesungen über Pathologie below.

- Handbuch der Speciellen Pathologie und Therapie, prepared in collaboration with others (1854–76)

- Vorlesungen über Pathologie (1862–72)

- Die krankhaften Geschwülste (1863–67)

- Ueber den Hungertyphus (1868)

- Ueber einige Merkmale niederer Menschenrassen am Schädel (1875)

- Beiträge zur physischen Anthropologie der Deutschen (1876)

- Die Freiheit der Wissenschaft im Modernen Staat (1877)

- Gesammelte Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der offentlichen Medizin und der Seuchenlehre (1879)

- Gegen den Antisemitismus (1880)

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Rudolf Virchow, Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre, 1858

- [2] Das Jahrhundert der Medizin. Triumphe der Heilkunst Dank Chirurgie und Rettungswesen, Antibiotika, Impfungen undHygiene hat die Heilkunst im 20. Jahrhundert mehr Erfolge errungenals in den Jahrtausenden davor at Spiegel Online

- [3] Biography of Rudolph Virchow at the Humboldt University of Berlin

- [4] Marco Steinert Santos. Virchow: medicina, ciência e sociedade no seu tempo

- [5] Ernst Haeckel and the Phyletic Museum, SciHi Blog

- [6] Works by or about Rudolf Virchow at Internet Archive

- [7] Newspaper clippings about Rudolf Virchow in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [8] Rudolf Virchow at Wikidata

- [9] Ted Schrecker, Rediscovering Virchow, revisiting Brecht: Health politics for a new Gilded Age, Inaugural Lecture at Queen’s Campus, Stockton on Friday 7th March 2014, DurhamUniversity @ youtube

- [10] Consuming Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century: Narratives of Consumption, 1700-1900, edited by Tamara S. Wagner and Narin Hassan (Lexington Books, 2007), p. 19.

- [11] Zweite Vorlesung, 17. Februar 1859. In: Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre, Verlag von August Hirschwald, Berlin 1868, S. 25, DTA

- [12] Timeline for Rudolf Virchow, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #09 | Whewell's Ghost