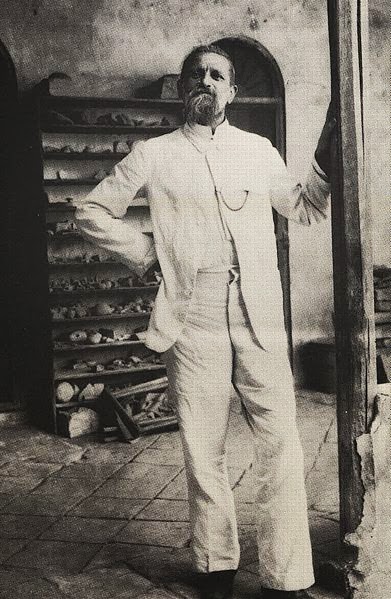

Robert Koldewey (1855 – 1925)

On September 10, 1855, famous German architect and self-trained archeologal historian Robert Johann Koldewey was born. He is best known for his discovery of the ancient city of Babylon in modern day Iraq, where he excavated the foundations of the ziggurat Marduk, and the famous Ishtar Gate.

Robert Koldewey – Early Years

Robert Koldewey was bornin Blankenburg (Harz Mountains), Duchy of Braunschweig, to the customs officer Hermann Koldewey and his wife Doris, born copper. He first attended the grammar school in Braunschweig. In 1869 his family moved to Altona, where he came to the Christianeum as a Tertian and passed his school-leaving examination there in 1875. After an apprenticeship of about two years in the building trade he began studying architecture, archaeology and art history in Berlin, Vienna and Munich. He completed his architectural studies in 1881 with a building foreman’s examination. Koldewey then worked as a government building supervisor for the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg and was probably admitted to the Hamburg Architects’ and Engineers’ Association on this occasion. Through this he came into friendly contact with Franz Andreas Meyer, the uncle of the well-known archaeology researcher Eduard Meyer, and with Alfred Lichtwark, the first director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Especially in the years until 1895, which were marked by professional and financial insecurity, both worked as patrons of Koldewey.

First Excavations

In 1882 and 1883 Koldewey participated in the excavations of Assos in the southern Troas as an employee of the excavation team of the American excavation expedition under Joseph Thacher Clarke and Francis Henry Bacon. His work there in 1885 earned him the commission of the German Archaeological Institute to carry out excavations on Lesbos. Together with the Orientalist Bernhard Moritz, he travelled Mesopotamia in 1887, where a preliminary investigation of the Sumerian cities of Nina (Surghul) and Lagaš (El-Hiba) was carried out. In 1889 he carried out excavations in Neandria. In 1890-1891 and 1894 Koldewey participated in the excavations of the Aramaic city Sam’al (Zincirli) in southeastern Turkey led by Felix von Luschan. From January to July 1892 and from October 1893 to January 1894 he travelled together with Otto Puchstein to Lower Italy and Sicily, where they measured and described the temples there. Robert Koldewey made views and schematic drawings of the temples. In 1894 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Freiburg for his investigations. In 1895 Koldewey accepted a position as a teacher at the Baugewerbeschule in Görlitz, an activity he did not like, as can be seen from his letters to Puchstein.

Babylon

In winter 1897/98 Koldewey traveled together with the Orientalist Eduard Sachau to a preliminary expedition to Mesopotamia to find suitable sites for future excavations of the German Oriental Society founded on January 24, 1898. He visited among others Kal’at Schergât (Aššur), Warka (Uruk), Kujundschik (Ninive) and Senkere (Larsa). Babylon (Kas’r) was chosen as the excavation site, mainly because of his arguments, which he supported by the use of coloured glazed bricks, although Assur had originally been the subject of discussion; Ninive retired because the English were already active here. The effect that Koldewey was able to achieve with the glazed relief fragments before the Commission of the Museums in Berlin was also decisive for the financing of the elaborate enterprise by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, the Prussian State and emperor Wilhelm II. On December 12, 1898 Koldewey set off for the Euphrates, and on March 26, 1899 the excavations of Babylon in present-day Iraq began. Koldewey’s activities on the Euphrates, initially planned for only five years, only ended in 1917 with the invasion of British troops in Baghdad during the First World War. In the 18 years he led among others the excavations of Assur, Fara (Schuruppak), Abu Hatab and Uruk from 1903 onwards, interrupted only by three relatively short holidays in Germany in the years 1904, 1910 and 1915.

Relief of colored glazed bricks, detail of the Ishtar Gate (Pergamonmuseum, Berlin)

Coming Home

After his return from Mesopotamia Koldewey settled in Berlin and worked as curator for foreign affairs of the Berlin museums. In 1921 he supported colleagues during excavations in Arkona on the island of Rügen, including Carl Schuchhardt, who later published Koldewey’s letters in 1925. Robert Koldewey died in Berlin at the age of 70 after a long period of suffering, which was due to the strains of his excavation in the Orient. At the Park Cemetery Lichterfelde in Steglitz-Zehlendorf is his grave in the form of a Zikkurat.

In an obituary on Koldewey that appeared in the Gnomon, the archaeologist Carl Schuchhardt ruled: “The generation of the great German excavators is dying out. They were peculiar and impressive figures, from Schliemann to Humann, Conze, Dörpfeld to Koldewey, because each had sought his own way and created his own gait. Robert Koldewey shall remain among them in honour!

Robert Koldewey’s Work

In the first half of the 19th century, research trips had been privately financed throughout. Collections, such as those of the resident of the East India Company in Baghdad, Claudius James Rich, who acquired the British Museum in 1825, had led to major English excavations in Nimrud and Ninive in the 1840s. Koldewey’s special interest in the practice of archaeological excavation was not only supported by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft and its well-known initiator and patron Henri James Simon, but also by the archaeology-loving Emperor Wilhelm II. In the course of a public debate about the theses of Friedrich Delitzsch, which also began in 1902, Koldeweys had noticed a dependence of the biblical writings on Babylon on the basis of a comparison of the Old Testament with the cuneiform scriptures, and as early as 1900 Koldeweys’ reports of his excavations on the Euphrates sent to Berlin attracted more attention; under the title Das wiedersertehende Babylon (Babylon Resurrected). Until 1925 they experienced the results of the German excavations in four editions.

Robert Koldewey found the Processional Way of Babylon with the Ishtar Gate, the palaces of Nebuchadnezzar and the foundations of the Tower of Babel mentioned in the Old Testament and Herodotus. The latter were partially excavated under his direction. In addition, he had participated in the excavations of the German Oriental Society in Zincirli (Sam’al) and in a preliminary investigation, together with his assistant Walter Andrae, had prepared the later excavations in Baalbek. The Hanging Gardens of the Semiramis (one of the wonders of the world) suspected by Koldewey near the Processional Way probably were not there. On the other hand, findings from more precise evaluations of the ancient texts and the distance from the Euphrates too great for irrigation speak against this. Koldewey’s excavation logistics are still considered exemplary today. His methodology supplemented the preservation of the individual fragments by the systematics of an exact recording of their sites within the excavation layers and thus made it possible to obtain information about the respective fate of the buildings and thus also about the history of the ancient city of Babylon. Today, Robert Koldewey has been awarded the merit of having increased the interest of archaeological oriental research in the historical nature of its buildings in terms of technology, function and aesthetics. His estate is kept and researched in the Museum of the Ancient Near East in Berlin.

Steve Tinney, Rise of the City: How the great god Marduk built the city of Babylon, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Koldewey at World Archeology

- [2] Koldewey Society [German]

- [3] Material on Koldewey at the German National Library

- [4] Full-text scan of The Excavations at Babylon by Robert Koldewey, translated by Agnes S. Johns; London: Macmillan, 1914.

- [5] Robert Koldewey at Wikidata

- [6] Steve Tinney, Rise of the City: How the great god Marduk built the city of Babylon, Penn Museum @ youtube

- [7] Clayton, Peter A. and Martin J. Price, Ed. “The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” Routledge: New York, 1988

- [8] Barthel Hrouda: Koldewey, Robert. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, p. 459

- [9] Joachim Marzahn, Kathleen Erdmann: Robert Koldewey – ein Archäologenleben. Berlin 2005

- [10] Timeline of German archaeologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia