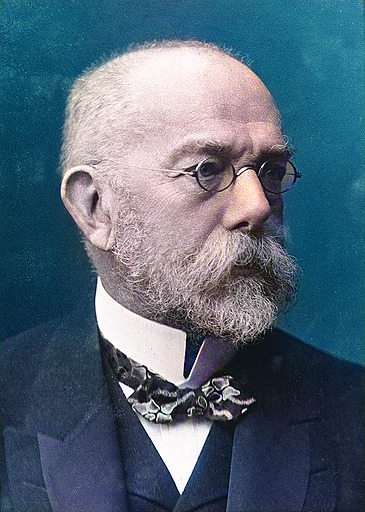

Robert Koch (1843-1910)

On December 11, 1843, Robert Koch, the founder of modern bacteriology, was born. He is known for his role in identifying the specific causative agents of tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax and for giving experimental support for the concept of infectious disease. As a result of his groundbreaking research on tuberculosis, Koch received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.

“When the doctor walks behind the coffin of his patient, sometimes the cause of the effect follows.”

– Robert Koch

The Life of Robert Koch

Robert Koch was born in Clausthal, Lower Saxony, as the third of a total of 13 children of Hermann Koch (1814-1877), the Steiger and later Geheimen Bergrat and his wife Mathilde (née Biewend, 1818-1871). Of the children, nine boys and two girls survived infancy. Robert’s father was quickly promoted and from 1853 supervised the entire mining of the Oberharz. As a young boy, Robert Koch learned reading and writing auto didactic and starting from 1848 he was taught by a private teacher followed by a grammar school. His grandfather was the one who introduced the curious boy how to handle the microscope, which highly influenced his decision in enrolling at the University of Göttingen, Germany in order to study medicine. Right at the end of his time at the university, Koch was taught by Rudolf Virchow,[3] the father of modern pathology. In the 1870s during the Franco-Prussian War, Koch gained much experience with the typhoid fever and started with own studies on bacteria. After leading an expedition researching for cholera in India and Egypt, Robert Koch started his career in Berlin. In 1885, he became professor at the institute for hygiene, which was part of the university of Berlin and retired in 1904.

Research on Anthrax

Koch’s influence on modern medical science is incredible. However, many people think of Koch as the discoverer of Bacillus anthracis. The bacillus anthracis was discovered by Aloys Pollender already in 1849. In 1863 Casimir Davaine had at least probably made a connection between the bacteria and the disease. Koch used anthrax to investigate a cattle disease that played a major role in the countryside but could also affect people. For his microscopic studies, he developed the hanging drop technique, in which the microbes are cultivated in a drop on the underside of a microscope slide. He used aqueous humor from bovine eyes as the nutrient fluid. This arrangement enabled him to detect bacteria in the blood of infected animals and observe how they formed spores and how these spores were converted back into bacteria. He later colored the actually transparent spores, a technique to which he had been inspired by Carl Weigert. When he artificially infected laboratory animals – such as guinea pigs or rabbits – they died of anthrax. He also succeeded in documenting the pathological process by which bacteria damage blood vessels. In the end, Robert Koch proved conclusively that the bacterium was able to cause a disease that was dangerous for both, humans and animals. The publication on the topic was published in 1876. Also, Robert Koch always used the latest technology during his studies and even used photography to record his findings.

Experiments on Tuberculosis

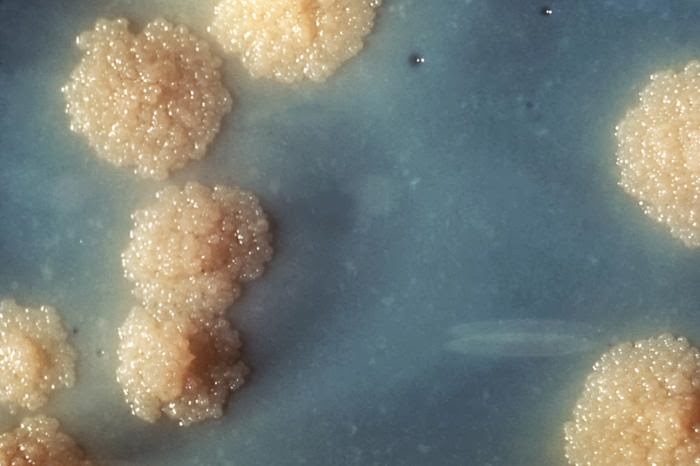

In the 1880’s, Koch started his experiments on tuberculosis. In these years, many scientists did not believe that the illness was infectious. Koch began experimenting with guinea pigs, which was at first more fruitful than a culture medium. He innovated the procedure drastically and finally, at attempt number 271, he discovered the causative agent. Shortly after, Koch held his very famous speech at the physiological society of Berlin on his findings and it is reported that the audience was so stunned and impressed that afterwards, that there was complete silence. The effect was immense. Tuberculosis was finally accepted as a “stand alone” illness and Koch became famous.

close-up of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture revealing this organism’s colonial morphology

Bacteriology and Hygiene

The subject of bacteriology and hygiene was finally accepted widely. Unfortunately for Koch, he was then appointed professor in Berlin, a task that he never really enjoyed and that made him quite sick, due to too much stress. In the meantime, Louis Pasteur managed to accomplish several scientific experiments that made him famous in the field as well.[4]

Unfortunate Events

“One day man will have to fight noise just as relentlessly as cholera and the plague.”

– Robert Koch

Even more unfortunate was the fact that Koch announced to have found a treatment against tuberculosis in 1890. Since about every 7th German citizen died of the disease, a huge euphoria was noticeable, when the well trusted scientist announced this discovery in Berlin. However, later on it was found out that Koch himself did not really know all ingredients of the mysterious treatment and that it even worked counterproductive for many patients.

Last Years

Despite this scandal, Koch was one of the most important scientists of his time, wherefore he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905 for his achievements. At the beginning of the 20th century Koch made a prematurely aged impression. On his travels he had been infected several times with tropical diseases, including malaria. In April 1910 he fell seriously ill. He complained of pain in his left chest and shortness of breath. On 23 May 1910 he moved into a sanatorium in Baden-Baden. On the evening of 27 May 1910 he was found lifeless at the open balcony door.

William Ayliffe, Twenty-first Century Threats: Tuberculosis, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Robert Koch’s biography at the Nobel Foundation website

- [2] Robert Koch Biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- [3] Robert Virchow, father of modern pathology , SciHi Blog

- [4] Louis Pasteur – the Father of Medical Microbiology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Edward Jenner’s Fight against Smallpox, SciHi Blog

- [6] Works by or about Robert Koch at Internet Archive

- [7] Robert Koch at Wikidata

- [8] William Ayliffe, Twenty-first Century Threats: Tuberculosis, Gresham College @ youtube

- [9] Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). “Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate”. Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (11): 854–855.

- [10] Lakhani, S. R. (1993). “Early clinical pathologists: Robert Koch (1843-1910)”. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 46 (7): 596–598.

- [11] Blevins, Steve M.; Bronze, Michael S. (2010). “Robert Koch and the ‘golden age’ of bacteriology”. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 (9): e744–751.

- [12] Ernst, H. C. (1918). “Robert Koch (1843-1910)”. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 53 (10): 825–827.

- [13] Timeline for Robert Koch, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #22 | Whewell's Ghost