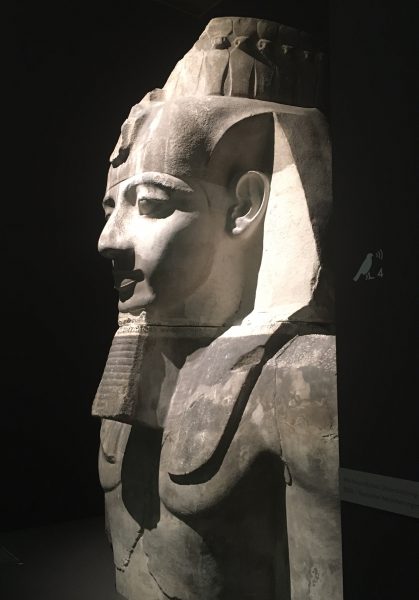

Ramesses II (1303-1213 B.C.), plaster cast of a colossal bust of Ramesses II, 1873, from SMB Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin

Ramesses II was born 1303 BC, third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Ramesses II often is regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian Empire. His successors often referred to him as “the Great ancestor”. The reason, why we include this ancient Egytian ruler in SciHi Blog is not only his historical relevance. Recently we have been invited to join the Ramesses II exhibition at the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe [1,2], where rare and famous artefacts from all over the world have been joined to form this great exhibition of which we will report today.

Ramses’ Family

Ramses’ family, of nonroyal origin, came to power some decades after the reign of the religious reformer Akhenaton (Amenhotep IV, 1353–36 B.C.) and set about restoring Egyptian power in Asia, which had declined under Akhenaton and his successor, Tutankhamen.[3,5] At age fourteen, Ramesses was appointed Prince Regent by his father Seti I. He is believed to have taken the throne in his late teens and is known to have ruled Egypt from 1279 B.C. to 1213 B.C. The early part of his reign was focused on building cities, temples, and monuments. He is known as Ozymandias in the Greek sources, from a transliteration into Greek of a part of Ramesses’ throne name, Usermaatre Setepenre, “The justice of Rê is powerful – chosen of Rê“.

Ramesses II receiving the gift of life from the deities Isis and Horus, Abydos, temple of Ramesses II., Paris, Musée du Louvre.

The Battle of Kadesh

Early in his life, Ramesses II embarked on numerous campaigns to restore possession of previously held territories lost to the Nubians and Hittites and to secure Egypt’s borders. He also was responsible for suppressing some Nubian revolts and carrying out a campaign in Libya. Although the Battle of Kadesh often dominates the scholarly view of the military prowess and power of Ramesses II, he nevertheless, enjoyed more than a few outright victories over the enemies of Egypt. The Battle of Kadesh in Ramesses` fifth regnal year was the climactic engagement in a campaign that he fought in Syria, against the resurgent Hittite forces of Muwatallis. The pharaoh wanted a victory at Kadesh both to expand Egypt’s frontiers into Syria, and to emulate his father Seti I’s triumphal entry into the city just a decade or so earlier. He also constructed his new capital, Pi-Ramesses. There he built factories to manufacture weapons, chariots, and shields, supposedly producing some 1,000 weapons in a week, about 250 chariots in two weeks, and 1,000 shields in a week and a half.

Expanding the Empire

After these preparations, Ramesses moved to attack territory in the Levant, which belonged to a more substantial enemy than any he had ever faced in war: the Hittite Empire. Ramesses’s forces were caught in a Hittite ambush and outnumbered at Kadesh when they counterattacked and routed the Hittites, whose survivors abandoned their chariots and swam the Orontes river to reach the safe city walls. Ramesses, logistically unable to sustain a long siege, returned to Egypt

Winning a Battle but Loosing a War

The Battle of Kadesh is one of the very few from pharaonic times of which there are real details, and that is because of the king’s pride in his stand against great odds; pictures and accounts of the campaign, both an official record and a long poem on the subject, were carved on temple walls in Egypt and Nubia, and the poem is also extant on papyrus.[3] Although the Egyptians were able to survive a terrible predicament in Kadesh it was not the splendid victory that Ramesses sought to portray but rather a stalemate in which both sides sustained heavily losses. Even though Ramesses technically won the battle, he ultimately lost the war, when Muwatallis and his army retook Amurru and extended the buffer zone with Egypt further southward. In 1258 B.C. Ramesses II signed the Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty, one of the earliest known peace treaties in the world and the only ancient Near Eastern treaty for which both sides’ versions have survived.

The Ramesseum and Abu Simbel

One measure of Egypt’s prosperity is the amount of temple building the kings could afford to carry out, and on that basis the reign of Ramses II is the most notable in Egyptian history, even making allowance for its great length.[3] Ramesses built extensively throughout Egypt and Nubia, and his cartouches are prominently displayed even in buildings that he did not construct. His memorial temple Ramesseum, was just the beginning of the pharaoh’s obsession with building. Oriented northwest and southeast, the Ramesseum temple was preceded by two courts. An enormous pylon stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king looming up at the back. Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite statue of the enthroned pharaoh, 17 metres high and weighing more than 1,000 tonnes. When he built, he built on a scale unlike almost anything before. Ramesses decided to eternalize himself in stone, and so he ordered changes to the methods used by his masons. The elegant but shallow reliefs of previous pharaohs were easily transformed, and so their images and words could easily be obliterated by their successors. Ramesses insisted that his carvings be deeply engraved into the stone, which made them not only less susceptible to later alteration, but also made them more prominent in the Egyptian sun, reflecting his relationship with the sun deit, Ra. In 1255 B.C. Ramesses and his queen Nefertari had traveled into Nubia to inaugurate a new temple, the great Abu Simbel. It is an ego cast in stone; the man who built it intended not only to become Egypt’s greatest pharaoh, but also one of its deities. At Karnak, the most holy of temples, a field of 134 columns were carved, each more than 20 metres tall and shaped like papyrus trees.

‘The Great Belzoni’ himself was acting as a tour guide for the Ramesses II exhibition at the Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe

Personal Life

Of Ramesses’ personal life virtually nothing is known. His first and perhaps favourite queen was Nefertari; the smaller temple at Abu Simbel was dedicated to her. By the time of his death, aged about 90 years, Ramesses was suffering from severe dental problems and was plagued by arthritis and hardening of the arteries. He had made Egypt rich from all the supplies and riches he had collected from other empires. He had outlived many of his wives and children, of which he is said to have more than 100, and left great memorials all over Egypt. Nine more pharaohs took the name Ramesses in his honour. After his death Egypt was forced on the defensive but managed to maintain its suzerainty over Palestine and the adjacent territories until the later part of the 20th dynasty, when the migration of militant Sea Peoples into the Levant ended Egypt’s power beyond its borders.[3]

We would like express our gratitude to the Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe, as well to the Karlsruher Tourismus GmbH for the invitation to the Ramesses II exhibition. It was a great experience and is highly recommended!! The exhibition continues until June 18, 2017.

Kristian Bonnici, Ramses The Great: The Founder of Public Relations, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Badisches Landesmuseum, website

- [2] Ramses, divine ruler on the Nile, at Badisches Landesmuseum

- [3] Ramesses II, King of Egypt, at Britannica Online

- [4] Joshua J. Mark, The Battle of Kadesh & the First Peace Treaty, at Ancient History Encyclopaedia

- [5] The Archeological Discovery of the Century – Tutankhamun’s Tomb, SciHi blog, November 26, 2012.

- [6] Ramesses II at Wikidata

- [7] Kristian Bonnici, Ramses The Great: The Founder of Public Relations, Kristian Bonnici @ youtube

- [8] Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1996). Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Translations. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- [9] Tyldesley, Joyce (2000). Ramesses: Egypt’s Greatest Pharaoh. London: Viking/Penguin Books.

- [10] Timeline of Egyptian pharaos, via Wikidata