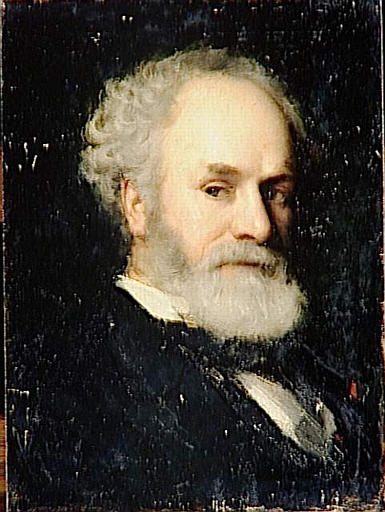

Pierre Jules César Janssen (1824 – 1907)

When watching the total eclipse on August 18, 1868 in Madras, British India, French astronomer Pierre Janssen discovered the new chemical element Helium. Janssen also is credited with discovering the gaseous nature of the solar chromosphere.

Youth and Education

Janssen was born in Paris in 1824. An accident when he was young left him extremely lame and it is for this reason that he was unable to go to school. He studied at home and, at the age of 16, when he started to work as a bank clerk. Janssen continued studying mathematics in his spare time and he eventually entered the faculty of sciences of the University of Paris to study mathematics and physics, where he graduated in 1852 and obtained his doctorate in 1860. He taught at the Lycée Charlemagne in 1853, and in 1865 he became professor of physics at the École Speciale d’Architecture in Paris. Despite his handicap, Janssen was an avid traveller always in pursuit of scientific knowledge.[2] His energies were mainly devoted to various scientific missions entrusted to him.

An avid Observer of Solar Eclipses

Thus in 1857 Janssen went to Peru in order to determine the magnetic equator. In 1861 – 1862 and 1864, he studied telluric absorption in the solar spectrum in Italy and Switzerland; in 1867 he carried out optical and magnetic experiments at the Azores; he successfully observed both transits of Venus, that of 1874 in Japan, that of 1882 at Oran in Algeria; and he took part in a long series of solar eclipse-expeditions, e.g. to Trani (1867), Guntur (1868), Algiers (1870), Siam (1875), the Caroline Islands (1883), and to Alcosebre in Spain (1905). To see the eclipse of 1870 he escaped from besieged Paris in a balloon (that eclipse was obscured by cloud cover, however).

Astronomers had been eagerly awaiting a total solar eclipse since 1859, when German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff figured out how to use the analysis of light to deduce the chemical composition of the sun and the stars. Scientists wanted to study the bright red flames that appeared to shoot out from the sun, now known to be dense clouds of gas called solar prominences. But until 1868, they thought the sun’s spectrum could only be observed during an eclipse.[3]

The 1868 Eclipse and a strange Spectral Line

In 1868 Janssen discovered how to observe solar prominences without an eclipse. While observing the solar eclipse of August 18, 1868, at Guntur, Madras State (now in Andhra Pradesh), British India, he noticed bright lines in the spectrum of the chromosphere, showing that the chromosphere is gaseous. Present, though not immediately noticed or commented upon, was a bright yellow line later measured to have a wavelength of 587.49 nm in the spectrum of the Sun. This was the first observation of this particular spectral line, and one possible source for it was an element not yet discovered on the earth.

The Spectrohelioscope

From the brightness of the spectral lines, Janssen realized that the chromospheric spectrum could be observed even without an eclipse, if only he could just figure out how to block other wavelengths of visible light. Working feverishly over the next few weeks, Janssen built the first spectrohelioscope, a device specifically designed to examine the spectrum of the sun.

The Discovery of Helium

Independently of Jenssen, Joseph Norman Lockyer in England was working on the same problem and set up a new, relatively powerful spectroscope on October 20, 1868, and observed the emission spectrum of the chromosphere during broad daylight, including same yellow line. In stunning synchronicity, the two scientists’ papers arrived at the French Academy of Sciences on the same day, and today both men are credited with the first sighting of helium. Within a few years, Lockyear worked with a chemist and they concluded that it could be caused by an unknown element, after unsuccessfully testing to see if it were some new type of hydrogen. This was the first time a chemical element was discovered on an extraterrestrial body before being found on the earth. Lockyer and the English chemist Edward Frankland named the element with the Greek word for the Sun, helios. Other scientists didn’t believe the astronomers’ account of a new element until 30 years later, when Scottish chemist William Ramsay discovered a perplexing earthly gas hidden inside a chunk of uranium ore.[3]

“Curse the man who invented helium! Curse Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen!”

— Principal Skinner, from The Simpson’s, episode ‘Bart’s Comet’

One main purpose of Jenssen’s spectroscopic inquiries was to answer the question whether the Sun contains oxygen or not. An indispensable preliminary was the virtual elimination of oxygen-absorption in the Earth’s atmosphere, and his bold project of establishing an observatory on the top of Mont Blanc was prompted by a perception of the advantages to be gained by reducing the thickness of air through which observations have to be made. This observatory was built in September 1893, and Janssen, in spite of his advanced age of 69 years, made the ascent and spent four days taking observations.

A Pioneer in Astrophotography

However, it was his ‘L’Atlas de Photographies Solaires’, published in 1904, which made Janssen one of the great pioneers of astrophotography and one of the founders of modern solar physics. This remarkable work contains some 6,000 photographs of the Sun taken in the years 1876 to 1903 from the newly established Meudon Observatory, near Paris, which was later to be known as the Paris Astrophysical Observatory. Janssen died at Meudon on 23 December 1907.

Robert Field, 22. Helium Atom, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Pierre Janssen at Britannica Online

- [2] PIERRE-JULES-CESAR JANSSEN (1824 – 1907) at the Open Door Website

- [3] Hedley Legget: Aug. 18, 1868: Helium Discovered During Total Solar Eclipse, Wired 18.08.2009

- [4] Pierre Jules César Janssen – The Elemental Man

- [5] Gustav Kirchhoff and the Fundamentals of Electrical Circuits, SciHi Blog

- [6] Pierre Janssen at Wikidata

- [7] More articles about the Sun at SciHiBlog

- [8] Robert Field, 22. Helium Atom, MIT 5.61 Physical Chemistry, Fall 2017, MIT OpenCourseWare @ youtube

- [9] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Janssen, Pierre Jules César“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 155.

- [10] Jensen, William B. (2004). “Why Helium Ends in “ium”“. Journal of Chemical Education. 81 (7): 944.

- [11] “Pierre Jules Cesar Janssen”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 68 (4): 245–249. 1908.

- [12] Timeline of 19th century French Astronomers, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #06 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: No. 383: On politics, robotics, the five-and-dime and the power of dreaming big - Innovate Long Island