Pierre Corneille (1606 – 1684)

On June 6, 1606, French tragedian Pierre Corneille was born. Seen on a European scale, his entire oeuvre belongs to the Baroque era. Along with Molière [1] and Jean Racine,[7] he is considered one of the great playwrights of the French classical period.

“La raison et l’amour sont ennemis jurés.” (Reason and love are sworn enemies.)

– Pierre Corneille, La nourrice, La Veuve [The Widow], (1631),

Youth and Literary Beginnings

Pierre Corneille was the first of six children of a wealthy royal hunting and fishing supervisor to grow up in Rouen, where he also attended the Jesuit College and subsequently studied law. At the age of 18, he was admitted to the Rouen Parlement, the highest court in Normandy, as a trainee lawyer. When he was 22 years old (1628), his father bought him two smaller judgeships, one of them at the parlement. His real ambition, however, was to write poems and plays since his school days. When the famous actor Mondory appeared with his travelling troop in Rouen in 1629, Corneille offered him his comedy Mélite, which he had written in the previous year. This confusing play about six young people, who finally come together in three pairs, was successfully staged in Paris in the winter of 1629/1630 and helped Mondory to establish himself there with a new theater, the Théâtre du Marais.

The Salon of the Marquise de Rambouillet

In the following years Corneille wrote numerous pieces for the Marais. Although these early pieces are considered less important youth works today, they had a novel effect at the time because, despite their conventional appearance, they seemed to reflect contemporary society, and most of them also played explicitly in Paris. Correspondingly, they had passable to great success, La Galerie even very great success, and early on earned Corneille the status of a recognized author. Although he still lived in Rouen, where he also held his offices, his frequent visits to Paris had given him contact with literary circles and salons, including the Marquise de Rambouillet. Although Corneille was not considered a witty entertainer there, and there was little he could read from his pieces, the occasional poems he contributed to this or that social occasion were appreciated.

Ignoring the Three Aristotelian Unities

“Devine, si tu peux, et choisis, si tu l’oses.” (Guess if you can, choose if you dare.)

– Pierre Corneille, Léontine, Héraclius, act IV, scene IV.

In 1635, together with the somewhat younger Jean Rotrou, among others, he became a member of a group of five authors in the service of Cardinal Richelieu, who tried to make the theatre a place of political propaganda for a strengthening of the absolute monarchy. After two plays written together, Corneille stopped working, but received his annual pension of 1500 francs until Richelieu’s death in 1642. In the winter of 1635/1636 Corneille, again very successful, published L’Illusion comique, a comedy in which he worked with the popular baroque motif of theatre in the theatre and at the same time, in the spirit of his employer Richelieu, promoted the upgrading of the acting profession. L’Illusion is the last piece in which Corneille ignores the doctrine of the three Aristotelian Unities (place, time and plot) that has been the subject of lively debate in Parisian literary circles.

El Cid

“As great as kings may be, they are what we are: they can err like other men.”

– Pierre Corneille, Le Cid, Don Gomès, act I, scene iii.

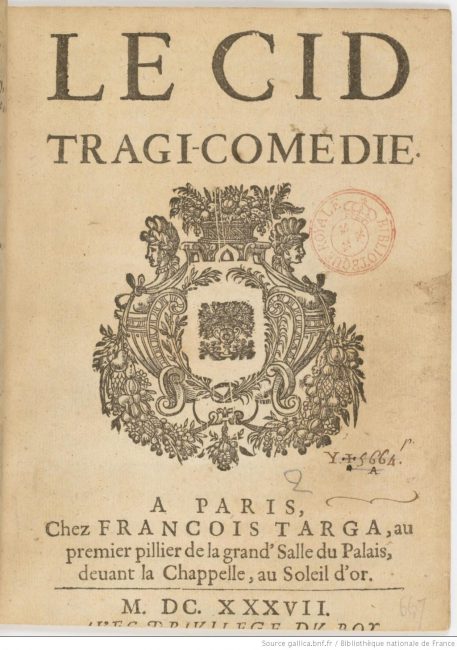

After the Spanish conquered the border and fortress town of Corbie in the summer of 1636, but lost it again after a long struggle, Corneille completed a tragicomedy in late autumn that seems to contain references to this battle: Le Cid. The performance of the play towards the end of the year was Corneilles final breakthrough. The play is regarded as the beginning of the high period of classical theatre. The plot of the Cid takes place in Spain in the 11th century and is based on the play Las Mocedades del Cid by Guillén de Castro from 1618, in which the heroic deeds of the young Cid, the medieval Spanish national hero, are described. Le Cid was one of the greatest events in French theatre history. The success was so spectacular that Louis XIII immediately elevated Corneille’s father to the aristocracy, with which the son was regarded as already born aristocratic.

Pierre Corneille, Le Cid, 1637 edition

Horace and Cinna

“To die for one’s country is such a worthy fate

That all compete for so beautiful a death.”

– Pierre Corneille, Horace (1639), act II, scene iii.

It was not until 1640, in the midst of Rouen’s insurrectionary upheavals, triggered by wartime tax increases and finally defeated by troops, that Corneille wrote his next play: Horace, a tragedy set in ancient Rome, in which he processed the legendary material of the battle between the Gentes of the Horatians and Curiatians. In early 1641, Corneille Cinna, ou la clémence d’Auguste completed a play about the conspiracy of some republican patricians against Emperor Augustus and his generous but also politically wise forgiveness when he discovers the plot. Horace and Cinna were very successful, and the latter piece, considered the author’s most formally successful, also became his most played after the Cid. Nevertheless, Corneilles’ artistic work faltered in the following years. In 1641 he married Marie de Lampérière, the eleven-year younger daughter of a judge, at the age of 35, which was very late for the time, and with whom he would have four sons and two daughters.

Mazarin and the Académie Francaise

It was not until the beginning of 1643 that Corneille published a new play, Polyeucte martyr (“Polyeuctos the Martyrs“), a “Christian tragedy” set around 250 in Armenia. It became a success with the audience, especially thanks to the love story interwoven with the religious events. Also in 1643, Corneille managed to win the favour of Cardinal Mazarin, Richelieu’s successor, with a poem of praise and an annual pension of 1000 francs. After Polyeucte, Corneille followed a whole series of pieces in which he followed the path taken by Le Cid, Horace and Cinna and thus earned himself a reputation. In 1647 Corneille was admitted to the Académie Française. But after this he got into the turmoil of the anti-absolutist revolts of the so-called Fronde (1648-52) against Queen Anna, who reigned for her still underage son Louis XIV.

Worthy of a Pension

“Le désir s’accroît quand l’effet se recule.” (Desire increases when fulfillment is postponed.)

– Pierre Corneille, Polyeucte (1642), act I, scene i.

The next play followed in 1660: the tragedy La Toison d’or (The Golden Fleece), commissioned by a wealthy nobleman, was performed with elaborate machines in summer at his Norman castle and in winter in Paris. In 1663, the new minister Colbert compiled a list of authors who were considered worthy of a pension by himself and his young king, in return for which they were expected to write regime friendly and panegyric texts. Corneille, too, came up with a gratifying 2000 francs. He lived up to the expectations that were directed at him immediately with the thank-you note Remerciement présenté au Roi en 1663 and did so frequently afterwards. As early as 1664, for example, he asked the king with a sonnet to reissue his letter of nobility, which had been collected together with hundreds of others by Colbert’s decree.

From Tragedy to Comedy

With the passably successful Œdipe and the much admired machine play La Toison d’or, Corneille had fully resumed his work as a playwright. As before, he mainly wrote tragedies with material from older, mostly Roman history (Sertorius, 1661/62; Sophonisbe, 1662; Othon, 1664; Agésilas, 1665/66; Attila, 1666/67). Altogether, however, he preferred now, imitating his meanwhile very successful brother Thomas, rather Romanesque actions. With this he tried to correspond to the taste of the public, which had changed greatly: due to the domestic calm that reigned after the victory of absolutism under Mazarin, but also due to the economic and cultural atmosphere of awakening that seized France after the end of the war against Spain (1659) and the beginning of the autocracy of the young Louis XIV in 1661.

Later Years

At the end of 1670, Corneille, urged by old friends and admirers as well as enemies and envious Racine,[7] tried a new comeback with the “comédie héroïque” Tite et Bérénice. At the same time, however, the now self-confident Racine brought out the same theme piece Bérénice, which was rated by the public as the much better one. Corneille was able to maintain his high status on the literary scene and in Parisian society until the end of his life, also thanks to the skill and influence of his always loyal brother and to his colleague Jean Donneau de Visé, who was faithful to Corneille in his magazine Le Mercure Galant, founded in 1672. He wrote his last piece Suréna in 1674 : it was a complete failure. After this, he retired from the stage for the final time and died at his home in Paris in 1684. His grave in the Église Saint-Roch went without a monument until 1821.

Legacy

“Each instant of life is a step toward death.”

– Pierre Corneille, Tite et Bérénice (Titus and Berenice) (1670), Tite, act V, scene i.

Corneille influenced all the playwrights beside and directly after him, especially Racine, with his about 35 plays; but he also remained a role model for the following generations of authors, e.g. for Voltaire.[2] Accordingly, he was and still is considered to be one of the greatest French playwrights and the greatest tragic artist alongside Racine, who is often regarded as the greatest despite his much narrower oeuvre.

Larry Norman, Charles Newell, The Theatrical Illusion: Corneille, Kushner, and the Baroque, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Animating the Absurd – Molière, Grandmaster of Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [2] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [3] Corneille and His Times, François M. Guizot; 1852, Harper & Bros., NY

- [4] Works by or about Pierre Corneille at Internet Archive

- [5] Works by Pierre Corneille at LibriVox

- [6] Pierre Corneille at Wikidata

- [7] The Untranslatable Linguistic Elegance of Jean Racine, SciHi Blog

- [8] Larry Norman, Charles Newell, The Theatrical Illusion: Corneille, Kushner, and the Baroque, The University of Chicago @ youtube

- [9] Ekstein, Nina. Corneille’s Irony. Charlottesville: Rookwood Press, 2007.

- [10] Nelson, Robert J. Corneille: His Heroes and Their Worlds. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1963.

- [11] Timeline for Pierre Corneille at Wikidata