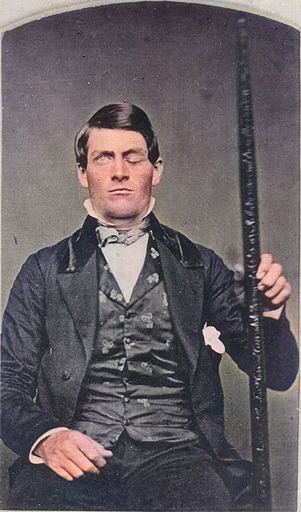

Phineas Gage (1823–1860)

On September 13, 1848, Phineas Gage (aged 25) was foreman of a work gang blasting rock while preparing the roadbed for the Rutland & Burlington Railroad outside the town of Cavendish, Vermont, when a large iron rod was driven completely through his head. Much of his brain‘s left frontal lobe was destroyed, reportedly affecting his personality and behavior. Phineas Gage influenced nineteenth-century discussion about the mind and brain, particularly debate on cerebral localization, and was perhaps the first case to suggest that damage to specific parts of the brain might affect personality.

“Yet there is something odd about the “recovered” Phineas. The doctor offers Phineas $1,000 for the pocketful of pebbles that Phineas has collected walking along the Black River near town. Dr. Harlow knows that Phineas can add and subtract, yet Phineas angrily refuses the deal.”

Phineas Gage Background and Accident

Phineas Gage grew up in New Hampshire and became a blasting foreman at railway construction projects. He was known to be a hard working and very efficient man, who was always active and completing every task perfectly. Gage was working on the line of the Rutland & Burlington Railroad, directing a group of workers when the explosion occurred. During an explosion, the tamping iron “entered on the [left] side of his face … passing back of the left eye, and out at the top of the head.” The 6 kg heavy iron cylinder was found 25 m away from the scene, completely covered in blood and brain parts. Surprisingly, Gage did not die. A few minutes after the accident, it is said that the wounded man was able to talk and even walked a little. When a doctor arrived, Gage vomited, which caused more brain to be pressed out of his head, falling on the ground.

The Aftermath

A few hours after the accident, Phineas Gage began to feel worse, running into some kind of coma, sometimes speaking a few syllables and his near death was expected. On October 3, he woke up and a few days later he was even able to stand up and walk a few steps. After a few weeks, he was seen on the streets again, going for walks and slowly recovering.

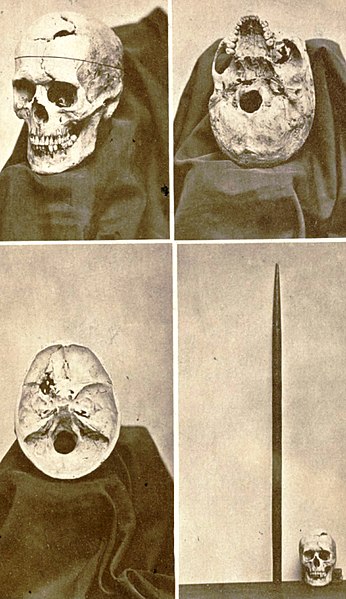

Frontispiece, showing multiple views of the exhumed skull, and tamping iron, of brain injury survivor Phineas Gage

Gage was unable to return to his original work and worked in a livery stable once in a while. He also began to travel a lot, working and taking care of the horses before his health began to worsen a little. But again he recovered and continued as a worker on a farm in Santa Clara. However, 12 years after the accident, his health situation decreased rapidly. He often suffered from convulsions and was unable to work most of the time. On May 21, he passed away and his skull was given to his doctor for scientific research.

Changing Behavior

According to contemporary scientists, both frontal lobes were highly damaged, while the right hemisphere seemed to be still intact. After the accident, several changes in Gage’s behavior were noticed. Since happenings like these were not really scientifically examined before, his mental changes were not researched in detail during his lifetime. Still, his doctor Harlow noticed that Gage would possible be an interesting case for a psychologist. His co-workers, who once described him as hard working, conscientious, active and efficient now found the communication with Gage very difficult. They now described him as “impatient, often irreverent, pertinaciously obstinate and fitful“. His friends noticed his growing unwilling to work and his overall restlessness. This clinical picture is nowadays known in neurology as frontal brain syndrome.

The Structure of the Brain

After Gage’s passing, controversial discussions on the brain structure, its functionality and mental changes broke loose. It was to be researched if specific regions of the brain represent various mental functions. Gage’s case represents the foundation of several new research fields considering brain and psychology that evolved in the 19th century. It is also assumed that Gage’s ‘crowbar case’ may have influenced psychosurgery. In 1867, the body was exhumed. The skull as well as the iron rod that was buried with it at that time were exhibited in the museum of the Harvard Medical School. In 1994 the skull was scanned by Hanna Damásio at the University of Iowa and a computer simulated a brain that fitted into this skull. The holes in the skull were used to determine which areas of the brain were damaged by the rod.

Lessons of the brain: the Phineas Gage case [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Phineas Gage at Brightbytes

- [2] Phineas Gage at New Scientist

- [3] Fleischman (2002). Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science

- [4] John Martyn Harlow (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head

- [5] Santiago Ramón y Cajal and the Microscopic Structure of the Brain, SciHi Blog

- [6] Walter Hess and his Mapping of the Brain, SciHi Blog

- [7] Roger Wolcott Sperry’s Split-Brain Research, SciHi Blog

- [8] Lessons of the brain: the Phineas Gage case, Harvard University @ youtube

- [9] Phineas Gage at Wikidata

- [10] Timeline of People with Traumatic Brain Injuries via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #09 | Whewell's Ghost