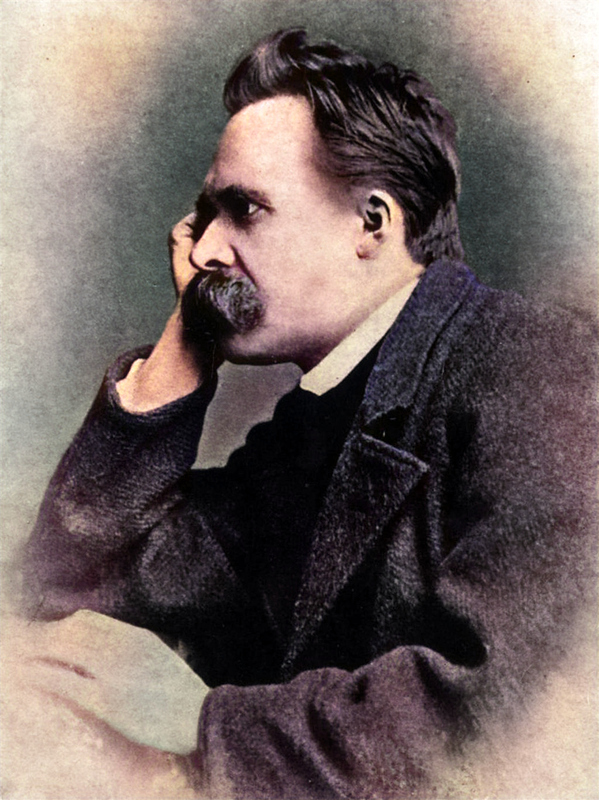

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

On October 15th, 1844, Friedrich Nietzsche was born. The German philosopher, cultural critic, and classical philologist lived and worked socially isolated for the most time and faced mainly criticism until his mental breakdown in 1889. He is best known for his concept of the ‘Übermensch‘ as well as the ‘death of God‘ and now counts as one of the most discussed and appreciated philosophers of all times.

“There are no facts, only interpretations.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Notebooks (Summer 1886 – Fall 1887)

Youth and Education

Friedrich Nietzsche was born in Röcken, a village near Lützen in the Merseburg district in the Prussian province of Saxony (today Saxony-Anhalt, Germany). His parents were the Lutheran priest Carl Ludwig Nietzsche and his wife Franziska. His father already died rather early and from 1850 to 1856 Nietzsche lived in the “Naumburg Women’s Household”, i.e. together with his mother, sister, grandmother, two unmarried aunts on his father’s side and the maid. Only the legacy of the grandmother, who died in 1856, allowed the mother to rent her own apartment for herself and her children.

He attended mainly private schools, where his linguistic talent was quickly detected. In 1864, he began studying philology and theology at the University of Bonn. During this period he was influenced by the works of David Friedrich Strauß, Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer and most importantly Arthur Schopenhauer.[4] This encouraged him (to the great disappointment of his mother) in the decision to discontinue his theological studies after one semester and to fully focus on classical philology. Nietzsche moved to Leipzig, where he would graduate. However, on Friedrich Ritschl’s recommendation and Wilhelm Vischer-Bilfinger’s instigation, Nietzsche was appointed associate professor of classical philology at the University of Basel in 1869, even before he had received his doctorate (honoris causa) and completed his habilitation. At his own request Nietzsche was released from Prussian citizenship after his move to Basel and remained stateless for the rest of his life.

The Wagner-Schopenhauer Period

“He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146

Another great influence to Friedrich Nietzsche depicts the composer Richard Wagner,[5] whom he deeply admired. In 1872, the so called Wager-Schopenhauer-period, in which he was able to publish his first major works, began. Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tradegy) was published in the same year, but was rejected by most of his colleagues. The work was an investigation into the origin of tragedy, in which he replaced the exact philological method with philosophical speculation. He developed his art psychology by attempting to explain Greek tragedy from the Apollonian-Dionysian pair of terms. Also to this period belong his four critics of contemporary civilization (Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen, 1873-1876) influenced by Wagner and Schopenhauer, that also couldn’t succeed. His admiration for Richard Wagner shrank during the famous Bayreuth opera festival. He was deeply unsatisfied in concerns of the level of acting as well as of the audience’s behaviors.

The same process took place with Schopenhauer. Nietzsche began to read Philipp Mainländer’s 200-page critique of Schopenhauer’s philosophy and a few days later he wrote that he had broken with Schopenhauer. The publication of Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (Human, All-too-Human, 1878) revealed the alienation of Wagner and Schopenhauer’s philosophy. This the Wagner-Schopenhauer-period and started his time as a free intellectual.

A Free Intellectual

“Our destiny exercises its influence over us even when, as yet, we have not learned its nature: it is our future that lays down the law of our today.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All too Human, (1878), Preface 7

Driven by his illnesses in the constant search for climate conditions that were optimal for him, he now traveled a lot and lived as a freelance author in various places until 1889. He published his book ‘The Dawn‘, in which he questions the development and the substance of religious and moral systems. He also released ‘The Gay Science‘, which ended this free period Nietzsche’s.

In 1882 he met Lou von Salomé through his friends Meysenbug and Rée in Rome. Nietzsche quickly made far-reaching plans for the “Trinity” with Rée and Salomé. The approach to the young woman culminated in a stay of several weeks together in Tautenburg, with Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth as chaperone. Nietzsche saw in Salomé, despite all appreciation, less an equal partner than a gifted pupil. He fell in love with her, asked Rée for her hand through his mutual friend, but Salomé refused. In the winter of 1882/1883, the relationship with Rée and Salomé broke up, partly because of Elisabeth’s intrigues. Nietzsche, who was plagued by suicidal thoughts in view of new episodes of illness and his now almost complete isolation – he had thrown himself over with his mother and sister because of Salomé – fled to Rapallo, where he put the first part of his masterpiece Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus spoke Zarathustra) on paper in only ten days.

While only a few friends remained to him after his break with Wagner and Schopenhauer’s philosophy, the completely new style in Zarathustra met with incomprehension even among his closest friends, which was at best covered up by politeness. Nietzsche was well aware of this and cultivated his loneliness, even though he often complained about it. In addition, he was plagued by money worries because his books were almost never bought. In 1885 he published the fourth part of the Zarathustra only as a private print with an edition of 40 copies, which were intended as a gift for “those who rendered outstanding services to him” and of which Nietzsche finally gave away only seven. The philosophical novel is divided into four parts and deals with the death of God and the new chances for the concept of the ‘Übermensch‘ as a new goal for humankind. In this work he illustrates five major virtues favored by the ‘Übermensch‘: Work and demolishment, love to oneself and to life as a whole as well as trust in one’s abilities, and courage to enforce one’s goals.

Nietzsche’s Last Period

“In the mountains of truth you will never climb in vain: either you will get up higher today or you will exercise your strength so as to be able to get up higher tomorrow.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human, 1878, II.293, maxim 358

His last period as philosopher and poet began in 1886, when he published his very critical and polemical works ‘Beyond Good and Evil‘ and ‘The Antichrist‘. In fact, interest in Nietzsche increased, albeit very slowly and hardly noticed by himself. Nietzsche continued to struggle with recurrent painful seizures that made constant work impossible. However, his writings and letters from autumn 1888, however, already indicate his incipient megalomania. In 1889, Nietzsche suffered from a mental breakdown, which brought his life as an intellectual to an end. The cause of the collapse was then diagnosed as progressive paralysis as a result of syphilis, which is now considered controversial. His pieces began to increasingly succeed when Nietzsche became an invalid, not knowing how many people he would influence with his critical mind and works, still highly discussed and cited by philosophy students and experts around the globe.

After several strokes, however, Nietzsche was partially paralyzed and could neither stand nor speak. On 25 August 1900, at the age of 55, he died of Frontotemporal Dementia in Weimar.

Alain Badiou: Lectures on Nietzsche [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Friedrich Nietzsche Society

- [2] Friedrich Nietzsche Website 1

- [3] Friedrich Nietzsche Website 2

- [4] The World according to Arthur Schopenhauer, SciHi Blog

- [5] Richard Wagner – Genius and Megalomania, SciHi Blog

- [6] Nietsche: Complete Works Collection

- [7] Friedrich Nietzsche at Wikidata

- [8] Alain Badiou: Lectures on Nietzsche, Alain Badiou with Bruno Bosteels from Columbia University: An extra Nietzsche seminar, Center for Contemporary Critical Thought @ youtube

- [9] Works by or about Friedrich Nietzsche at Internet Archive

- [10] Wicks, Robert (14 November 2007). “Friedrich Nietzsche”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [11] Cate, Curtis (2005). Friedrich Nietzsche. Woodstock, N.Y.: The Overlook Press.

- [12] Hollingdale, R. J. (1999). Nietzsche: The Man and His Philosophy. The Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 64. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–219

- [13] Kaufmann, Walter (1974). Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Princeton University Press.

- [14] Timeline for Friedrich Nietzsche, via Wikidata

Nice Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche . Thanks for sharing this Quotes.