The Salon de Refusés of 1863 took place in the Palais de l’Industrie in Paris

On May 15, 1863, the Salon des Refusés in Paris was opened, an exhibition of works rejected by the jury of the official Paris Salon. In 1863 the Salon jury refused two thirds of the paintings presented, including the works of Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissaro and Johan Jongkind, marking the birth of the avant-garde. Upon the protest of the artists, emperor Napoleon III decided to let the public judge and let the works be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.

The Annual Paris Salon

First at all, let’s have a look at the annual Paris Salon, sponsored by the French government and the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. The Paris Salon was intended as a showcase of the best academic art, established already in 1667. The Salon’s original focus was the display of the work of recent graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts, which was created by Cardinal Mazarin in 1648. Exhibition at the Salon de Paris was essential for any artist to achieve success in France for at least the next 200 years. Exhibition in the Salon marked a sign of royal favor and in later years it served likewise as an assurance of government and private commissions. In the 19th century the idea of a public Salon extended to an annual government-sponsored juried exhibition of new painting and sculpture, held in large commercial halls, to which the ticket-bearing public was invited. The 1848 revolution liberalized the Salon, the amount of refused works was greatly reduced. In 1849 medals were introduced.

History Paintings were ranked First

In the mid 19th century, fine arts had become a serious business not only in France. France during this period had something on the order of 5,000 writers and critics covering the art scene while there were 12,000 working artists in Paris alone.[3] Since the 18th century, the paintings were classified by genre, following a specific hierarchy; history paintings were ranked first, followed by the portrait, the landscape, the “genre scene“, and the still life. lower ranked genres were regarded less favourably. The increasingly conservative and academic juries were not receptive to the Impressionist painters, whose works were usually rejected, or poorly placed if accepted. The Salon opposed the Impressionists’ shift away from traditional painting styles. The jury, headed by the Comte de Nieuwerkerke, the head of the Academy of Fine Arts, was very conservative; near-photographic but idealized realism was expected, with all traces of brushwork erased leaving a polished finish. A rejected painting might be very bad news for an artist, since the Salon show provided the only opportunity in the French arts calendar for him to display his works to art collectors and dealers, as well as art critics and writers.[1]

Two thirds of the Paintings Refused

As early as the 1830s, Paris art galleries mounted small-scale, private exhibitions of works rejected by the Salon jurors. Private exhibits attracted far less attention from the press and patrons, and limited the access of the artists to a small public. In 1863 the Salon jury refused two thirds of the paintings presented (fewer than 2,218 pictures out of a total of over 5,000), including the works of Gustave Courbet,[6] Édouard Manet, Camille Pissaro [7] and Johan Jongkind. The rejected artists and their friends protested, and the protests reached Emperor Napoleon III. The Emperor’s tastes in art were traditional, however he was sensitive to public opinion. His office issued a statement: “Numerous complaints have come to the Emperor on the subject of the works of art which were refused by the jury of the Exposition. His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.“

The Salon des Refusés

More than a thousand visitors a day visited the alternative exhibition, soon dubbed as Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of Rejected Art). Overall, the exhibition program for the Salon des Refusés lists 780 works by 64 sculptors and 366 painters, along with a small number of printmakers and architects.[1] The journalist Emile Zola reported that visitors pushed to get into the crowded galleries where the refused paintings were hung, and the rooms were full of the laughter of the spectators.[8] Critics and the public ridiculed the refusés, which included such now-famous paintings as Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and James McNeill Whistler’s Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. But the critical attention also legitimized the emerging avant-garde in painting.

Éduard Manet: Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862/63)

Sparking Public Notoriety

Rejected by the Salon jury of 1863, Manet seized the opportunity to exhibit Déjeuner sur l’herbe and two other paintings in the 1863 Salon des Refusés. Déjeuner sur l’herbe depicts the juxtaposition of a female nude and a scantily dressed female bather in the background, on a picnic with two fully dressed men in a rural setting. The painting sparked public notoriety and stirred up controversy and has remained controversial, even to this day.

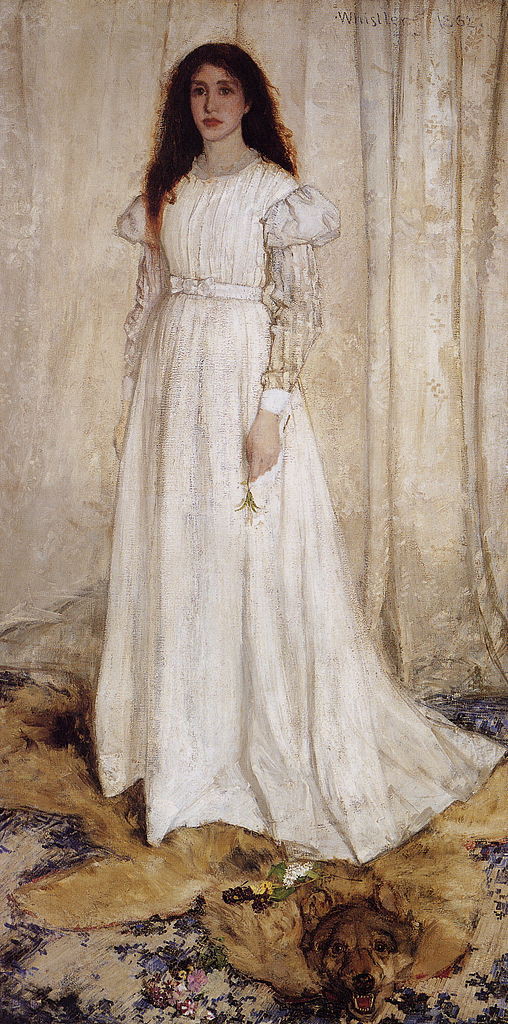

James Whistler Symphony in White no 1 – The White Girl (1862)

The White Girl

In 1861, James Abbott McNeill Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, a portrait of his mistress and business manager Joanna Hiffernan, created as a simple study in white. However, some thought the painting an allegory of a new bride’s lost innocence, while others linked it to Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, a popular novel of the time, or various other literary sources. In England, some considered it a painting in the Pre-Raphaelite manner. Countering criticism by traditionalists, Whistler’s supporters insisted that the painting was “an apparition with a spiritual content” and that it epitomized his theory that art should be concerned essentially with the arrangement of colors in harmony, not with a literal portrayal of the natural world.

The Salon des Independents

Despite a generally unfavorable press, the Salon des Refusés helped undermine the prestige of the official Salon, as artists began to organize their ownexhibitions with greater frequency, no longer feeling reliant on the official Salon for exposure.[2] The Salon des Refusés was so important, because, to a great extent, it legitimized the newly emerging forms of avant-garde art, and paved the way for the even more shocking style of “Impressionism”, which its exponents unleashed on Paris in 1874, in a series of independently organized exhibitions (1874-84).[1] The Impressionists successfully exhibited their works outside the traditional Salon beginning in 1874. Subsequent Salons des Refusés were mounted in Paris in 1874, 1875, and 1886, by which time the popularity of the Paris Salon had declined for those who were more interested in Impressionism. The Salon des Independants, organized by Georges Seurat, began in 1884, while the Salon d’Automne opened in 1903. Nowadays the term “Salon des Refusés” is used to denote any art exhibition devoted to the display of works rejected by a juried art show.[1] However, 1863 is considered as a turning point in the history of modern art and the Salon des Refusés is often cited as the beginning of truly modern painting.[2]

‘

Parme Giuntini, Manet: Realism Beyond Courbet | Modernity and Realism | Otis College of Art and Design, [9]

References and further Reading:

- [1] Salon des Refusés, Exhibition of Rejected Art, Paris 1863. Encyclopedia of Art History, at visual arts Cork

- [2] May 15, 1863: Paris’s Salon des Refusés Opens, In Great Events from History: The 19th Century, 1801-1900. 4 vols. Ed. John Powell, 1099-1101. Pasadena: Salem Press.

- [3] Jim Lane: The Salon des Refuses, at Humanities-web.org

- [4] Salon de Refusés at Wikidata

- [5] Salon de Refusés at Reasonator

- [6] Gustave Courbet and French Realism, SciHi Blog

- [7] Camille Pissaro and the Impressionistic Art Movement, SciHi Blog

- [8] J’Accuse – Émile Zola and the Dreyfus Affaire, SciHi Blog

- [9] Parme Giuntini, Manet: Realism Beyond Courbet | Modernity and Realism | Otis College of Art and Design, Otis College of Arts and Design @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of 19th century Avant garde, via DBpedia and Wikidata