First description of Homo heidelbergensis

On October 21, 1907 the worker Daniel Hartmann unearthed a mandibular in a sand mine in the Grafenrain Open field system of the Mauer community. The so-called Mauer 1 mandible is the oldest fossilized specimen of the genus Homo ever to be discovered in Germany. The Mauer 1 mandible is the type specimen of the species Homo heidelbergensis, a subspecies of Homo erectus.

In Search for Traces of Mankind

In 1907, Daniel Hartmann unearthed a mandibular in a sand mine in the Grafenrain Open field system of the Mauer community about ten kilometers southeast of Heidelberg in a depth of 24.63 meters, which he recognized to be the remains of a human. Already several years prior to the find, the Heidelberg scholar Otto Schoetensack had the workers of the sand mine urged for 20 years to pay attention to any fossils after the well-preserved skull of a forest elephant had come to light in this sand pit in 1887. The scientist had also taught the characteristics of human bones based on recent examples as he regularly visited the sand mine in search for “traces of mankind”.

A Mandible

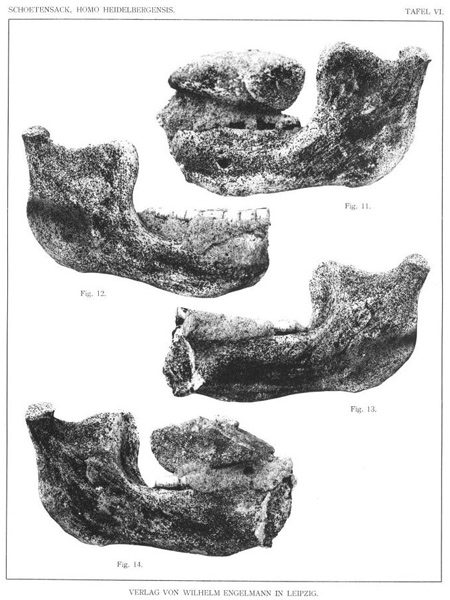

Unfortunately, the mandible was discovered only after it has been dug out and broken in two pieces. Further, a cemented crust stuck on and around the canines and molars due to the carbonation of calcium and the two frontal molars of the mandible’s left side sat a six inches long and about four inches wide boulder of limestone, probably Muschelkalk, firmly connected to the sand crust.

Homo Heidelbergensis

Schoetensack presented the results of his findings on the mandibular in a monograph titled “The lower jaw of Homo heidelbergensis from the sands of Mauer near Heidelberg“.[3] The mandible remains in the University’s Geological-Palaeontological Institute to this day as “the most valuable object in the natural history collections of the University of Heidelberg“. Later finds of the Mauer sand mine are the Hornstein artefacts, found in 1924 by Karl Friedrich Hormuth, which scholars interpreted as tools of Homo heidelbergensis. In 1933 Wilhelm Freudenberg discovered a frontal bone fragment which too, could be associated to Homo heidelbergensis. In 2010 the mandible’s age was for the first time exactly determined to be 609,000 ± 40,000 years. Previously, specialist literature had referred to an age of either 600,000 or 500,000 years on the basis of less accurate dating methods.

Evolution of Man

Today’s researchers consider Mauer 1 as an independent chronospecies. According to Chris Stringer, Homo heidelbergensis ranks separable between earlier Homo erectus and the more recent Neanderthal and Homo sapiens. Mauer 1 is also the last common ancestor of Neanderthal and anatomically modern man. However, there are also researchers who believe that the evolutionary development in Africa and Europe was a gradual process from Homo erectus via the representative of the findings assigned to Homo heidelbergensis towards Neanderthal. Any form of segregation is considered arbitrary, which is why these researchers forgo the name Homo heidelbergensis altogether. They classify the Mauer 1 man as a late local (European) form of Homo erectus. Others however concluded that the lower jaw of Mauer does not belong to the immediate ancestral line of modern man. He is regarded rather as a descendant of an early migration to Europe and Asia.

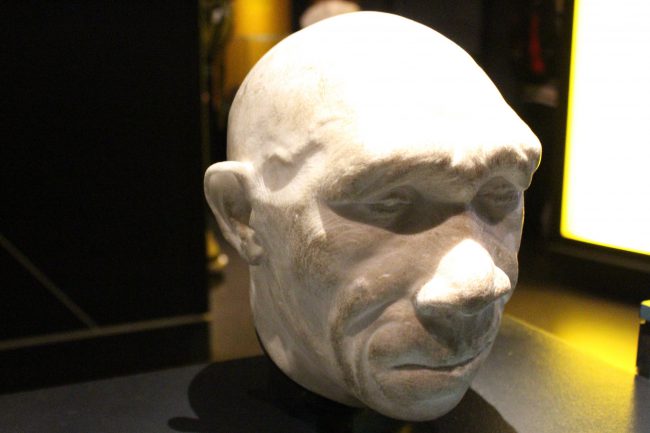

Bust of an H. heidelbergensis at the Natural History Museum, London, Emőke Dénes, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Homo heidelbergensis is regarded as a chronospecies, evolving from an African form of Homo erectus (sometimes called Homo ergaster). By convention, Homo heidelbergensis is placed as the most recent common ancestor between modern humans (Homo sapiens or Homo sapiens sapiens) and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens neanderthalensis). Many specimens assigned to Homo heidelbergensis likely existed well after the modern human/Neanderthal split.

Lindsay Barone, Species Shorts: Homo heidelbergensis, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Otto Schoetensack at Archive.org

- [2] Mauer 1 Mandible History (in German)

- [3] Otto Schoetensack: Der Unterkiefer des Homo Heidelbergensis aus den Sanden von Mauer bei Heidelberg. Ein Beitrag zur Paläontologie des Menschen. Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1908

- [4] Katerina Harvati: 100 years of Homo heidelbergensis – life and times of a controversial taxon. In: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 16, 2007, 85-94

- [5] Stringer, C. B. (2012). “The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908)”. Evolutionary Anthropology. 21 (3): 101–104.

- [6] Lindsay Barone, Species Shorts: Homo heidelbergensis, DNA Learning Center @ youtube

- [7] Mauer Mandible 1 at Wikidata

- [8] Map with hominid fossils, via Wikidata