Macbeth and the Witches (Johann Heinrich Füssli, 1741-1825)

On August 14, 1040 AD, Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, Mormaer of Moray, today better known as Macbeth, killed the Scottish King Duncan I. to become the new King of Scotland. But, he has to commit further murder to maintain his power. So far the story goes. Most of the rest we know from Shakespeare‘s adaptation of the historical events is merely pure fiction.[2,3]

Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Macbeth’s life, like that of his predecessor King Duncan I, had already progressed far towards legend by the end of the 14th century, when John of Fordun and Andrew of Wyntoun wrote their histories. In Shakespeare’s play (The Tragedy of MacBeth, about 1603-1607), Macbeth is portrayed initially as a valorous and good-hearted general to King Duncan, but who later is corrupted by ambition. He persuades himself that killing his king to take the throne is the right thing to do. His ambition is fostered by three witches whose prophecies however prove misleading, and his scheme is doomed to failure. Macbeth commits regicide and becomes King of Scotland. He thereafter lives in anxiety and fear, unable to rest or to trust his nobles. He leads a reign of terror until defeated by Macduff. The throne is then restored to the rightful heir, the murdered King Duncan’s son, Malcolm.

First Witch: When shall we three meet again

In thunder, lightning, or in rain?

Second Witch: When the hurly-burly’s done,

When the battle’s lost and won.

Third Witch: That will be ere the set of sun.

First Witch: Where’s the place?

Second Witch: Upon the heath

Third Witch:There to meet with Macbeth.First Witch: I come, Graymalkin!

Second Witch: Paddock calls.

Third Witch: Anon.

— William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of MacBeth, Scene I

Shakespeare’s Sources

Shakespeare’s source for the story is the account of Macbeth, King of Scotland; Macduff; and Duncan in Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587), a history of England, Scotland, and Ireland familiar to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, although the events in the play differ extensively from the history of the real Macbeth. The events of the tragedy are usually associated with the execution of Henry Garnet for complicity in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.[4] In Macbeth, however, Shakespeare does not confine himself to the Holinsheds Chronicles, but makes structural changes at various points. In Holinshed’s Chronicles Duncan is portrayed as a weak king who destabilises the empire through his excessive indulgence. In his account, Macbeth is a strict but righteous ruler for ten years, who, it is said, had a legitimate claim to the crown under ancient Scottish law before becoming a tyrant. Shakespeare also differs from Holinshed with regard to the character Banqo. Although he is also murdered by Macbeth in Holinshed, he does not only act as Macbeth’s accomplice in the regicide. It is assumed that Shakespeare relieved him in his play because the contemporary audience regarded him as the ancestor of the Stuarts and thus of King Jacob I. Another change concerns the figure of Lady Macbeth, who appears in the source solely as the wife of the protagonist without an essential role or function

Lady Macbeth

MacBeth’s wife, Lady Macbeth, who is only mentioned in one movement in Holinshed, becomes Shakespeare’s partner, who acts as both a protagonist and a contrasting figure. Lady Macbeth, became Queen of Scotland after goading her husband into committing regicide, but later suffered pangs of guilt for her part in the crime. She dies off-stage in the last act, an apparent suicide. Also in the play Lady Macbeth ambition is not only want her husband to be king, she also wants to be queen to rule over England. she wanted to be a part which she would grant her evilness to change the country.

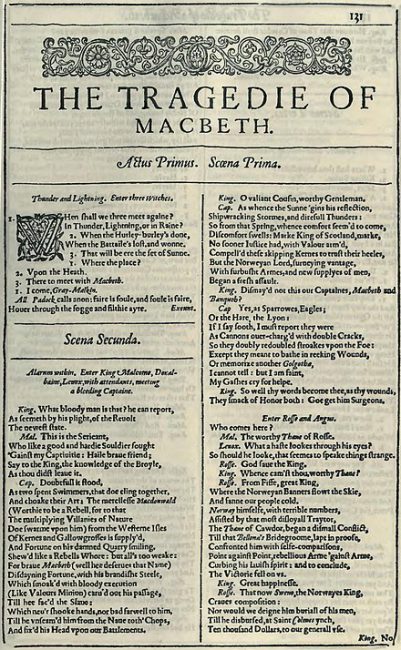

The first page of Shakespeare’s Macbeth from the First Folio (1623), PastelKos, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Turning the Story

In this way, Shakespeare turns the foundation of Holinshed’s history, which is already oriented towards the exemplary but has no special potential for statement, into a drama which, on the basis of a historical case, explores the problem of evil on the individual level of meaning as an individual human involvement in guilt and atonement, on the social-political level as overthrow and restoration, and on the metaphysical level as a confrontation between heavenly and hellly forces or, as the case may be, as the case may be. as a battle between nature and unnature, modelled and dramaturgically staged. Furthermore, Lady MacBeth has gained fame along the way, lending her Shakespeare-given title to a short story by Nikolai Leskov and the opera by Dmitri Shostakovich titled Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

Look like the innocent flower,

But be the serpent under it.

— William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of MacBeth, Lady Macbeth, Scene V

Macbeth in the Movies

The earliest known film Macbeth was 1905’s American short Death Scene From Macbeth, and short versions were produced in Italy in 1909 and France in 1910. Two notable early versions are lost: Ludwig Landmann produced a 47-minute version in Germany in 1913, and D. W. Griffith produced a 1916 version in America featuring the noted stage actor Herbert Beerbohm Tree.[6] In 1947, David Bradley produced an independent film of Macbeth, intended for distribution to schools, most notable for the designer of its eighty-three costumes: the soon-to-be-famous Charlton Heston. Orson Welles‘ 1948 Macbeth, in the director’s words a “violently sketched charcoal drawing of a great play,” was filmed in only 23 days and on a budget of just $700,000.[7] Joe MacBeth (Ken Hughes, 1955) established the tradition of resetting the Macbeth story among 20th-century gangsters. In 1957, Akira Kurosawa [9] used the Macbeth story as the basis for the universally acclaimed Kumunosu-jo. Roman Polanski‘s 1971 Macbeth was the director’s first film after the brutal murder of his wife, Sharon Tate, and reflected his determination to “show [Macbeth’s] violence the way it is”. William Reilly’s 1991 Men of Respect, another film to set the Macbeth story among gangsters, has been praised for its accuracy in depicting Mafia rituals, said to be more authentic than those in The Godfather or GoodFellas.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

— William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of MacBeth, Macbeth, Scene V

William Carroll, Macbeth and the Show of Kings, [8]

References and further Reading:

- [1] William Shakespeare’s MacBeth in Wikipedia

- [2] William Shakespeare: MacBeth, ebook at gutenberg.org

- [3] Brush Up Your Shakespeare, SciHi Blog

- [4] Remember, remember, the 5th of November – Guy Fawkes Gun Powder Plot, SciHi Blog

- [5] MacBeth at Wikidata

- [6] D. W. Giffith’s Birth of a Nation, SciHi Blog

- [7] Orson Welles’ Disputed Masterpiece Citizen Kane, SciHi Blog

- [8] William Carroll, Macbeth and the Show of Kings, Boston University on April 28, 2005, Boston University @ youtube

- [9] Akira Kurosawa and the Rashomon Effect, SciHi Blog

- [10] Coursen, Herbert R. (1997). Macbeth: A Guide to the Play. Greenwood Press.

- [11] Crawford, Robert (13 March 2010). “Macbeth, A True Story by Fiona Watson: The whole truth about Macbeth is not enough for Robert Crawford”. The Guardian.

- [12] Timeline of works based on MacBeth, via Wikidata