Lewis and Clark at the Columbia Rivers painting by Frederic Remington (1906), © Library of Congress

On May 14, 1804, American explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark departed for the first American expedition to cross what is now the western portion of the United States, departing from St. Louis on the Mississippi River making their way westward through the continental divide to the Pacific coast.

An American Expedition

To cross Northern America from the east to the west, and doing this even more than 200 years ago, this really was an adventurous journey through the wilderness. It all started in 1803 with the so-called Lousiana Purchase, when U.S. president Thomas Jefferson bought the French owned territory of Lousiana for the U.S., comprising a huge area of more than 2 mio square kilometers, i.e. 12 present day U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Now, to

“find the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce“,

Jefferson commissioned an expedition of a select group of U.S. Army volunteers under the command of Captain Meriwether Lewis and his close friend Second Lieutenant William Clark. Of course, the primary objective of the expedition was to explore and map the newly acquired territory, to find a practical route across the Western half of the continent, and establish an American presence in this territory before Britain and other European powers tried to claim it. Jefferson hoped that the expedition would find a water route linking the Columbia and Missouri rivers. This water link would connect the Pacific Ocean with the Mississippi River system, thus giving the new western land access to port markets out of the Gulf of Mexico and to eastern cities along the Ohio River and its minor tributaries. Moreover, there were also scientific and economical objectives, i.e. to study the area’s plants, animal life, and geography, and to establish trade with local Indian tribes.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

Captain Meriwether Lewis was not a scientist to lead a scientific expedition, but demonstrated remarkable skills and potential as a frontiersman. Jefferson later justified his decision in the following way:

“it was impossible to find a character who to a complete science in botany, natural history, mineralogy and astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution and character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods and a familiarity with the Indian manners and character, requisite for this undertaking. All the latter qualifications Capt. Lewis has.”

Lewis in turn selected William Clark as second in command. Once Congress approved the funds for the expedition, it was prepared with sufficient black powder and lead for their flintlock firearms, knives, blacksmithing supplies, and cartography equipment. They also carried flags, gift bundles, medicine and other items they would need for their journey.

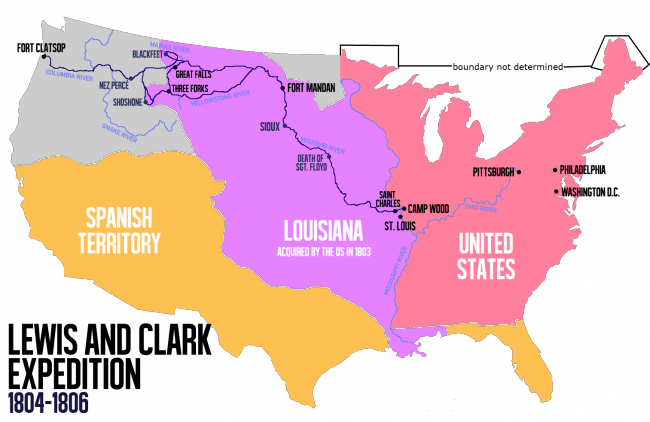

The Lewis and Clark American Expedition

Lewis and Clark’s expedition officially began on May 21, 1804 when they and the 33 other men of the ‘Corps of Discovery’ departed from their camp near St. Louis, Missouri, following the route of the Missouri River during which, they passed through places such as present-day Kansas City, Missouri and Omaha, Nebraska. On August 20, 1804, the Corps experienced its first and only casualty when Sergeant Charles Floyd died of appendicitis. Shortly after, they reached the edge of the Great Plains and also met their first Sioux tribe, the Yankton Sioux, in a peaceful encounter. The expedition party continued westward (upriver), and camped for the winter in the Mandan nation’s territory. For several days Lewis and Clark met in council with Mandan Indian chiefs. Here they also met a French-Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau, and his young Shoshone wife Sacagawea. Charbonneau at this time began to serve as the expedition’s translator.

Route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Following the Missouri River

Following the Missouri to its headwaters, and over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass, the party descended the mountains in canoes by the Clearwater River, the Snake River, and the Columbia River, past Celilo Falls and past what is now Portland, Oregon at the meeting of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. Since there was no other means of long distance communication but letters, Lewis and Clark had to send messengers with descriptions of the events of their journey back to Jefferson. The descriptions had to be kept from getting damaged because if the writings got wet the ink would blur. To keep them safe they put the descriptions in bottles. In their first description in autumn 1805, they chronicled 108 plant species and 68 mineral types.

“Ocean in view! O! the joy”

– Entry in the journal of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (November 7, 1805)

…West towards the Pacific Ocean

At last, the Corps reached the Pacific Ocean in December 1805 and built Fort Clatsop on the south side of the Columbia River to wait out the winter. On March 23, 1806, Lewis and Clark and the rest of the Corps again left Fort Clatsop and began their journey back to St. Louis. Once reaching the Continental Divide in July, the Corps separated for a brief time so Lewis could explore the Marias River, a tributary of the Missouri River. They then reunited at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers on August 11 and returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Although Lewis and Clark did not achieve their first objective to find a direct waterway from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, their expedition brought significant knowledge about the newly purchased lands in the west. Also peaceful relations to native Indians of the West could be established by Lewis and Clark, which was another of Jefferson’s objectives. The scientific value cannot be overestimated, because the expedition provided profound geographical knowledge about the topography of the Pacific Northwest and produced more than 140 maps of the region. Moreover, they documented over 100 animal species and more than 170 plants.

Alan Taylor, Lewis and Clark: An Overview of the Expedition, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Lewis and Clark Expedition at about.com

- [2] Teaching With Documents: The Lewis and Clark Expedition at the National Archives

- [3] Lewis and Clark at National Geographic”

- [4] Timeline for the historic Trail of Lewis and Clark

- [5] Lewis and Clark at Encyclopedia Britannica

- [6] more Lewis and Clark content at PBS

- [7] The Lewis and Clark Expedition at Wikidata

- [8] The Journals of Lewis and Clark hypertext from American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- [9] Works by William Clark at Project Gutenberg

- [10] “History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark: To the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean” published in 1814; from the World Digital Library

- [11] Alan Taylor, Lewis and Clark: An Overview of the Expedition, University of Virginia Alumni, Friends, & Families @ youtube

- [12] Steven E. Ambrose (1996). Undaunted Courage, Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. Simon and Schuster Paperbacks.

- [13] Wheeler, Olin Dunbar (1904). The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1904: A Story of the Great Exploration Across the Continent in 1804–6. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons

- [14] Timeline of North American Expeditions, via DBpedia and Wikidata