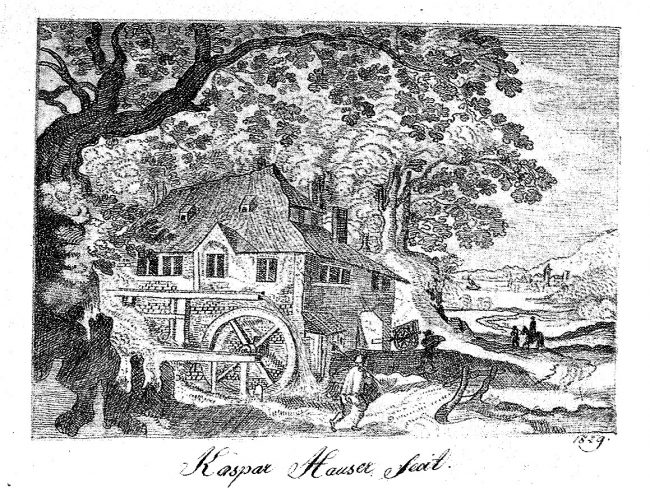

Painting of Kaspar Hauser (1812 – 1833)

On 26 May 1828, a teenage boy appeared in the streets of Nuremberg, Germany. The boy, who answered to the name Kaspar Hauser, claimed to have grown up in the total isolation of a darkened cell. Hauser’s claims, and his subsequent death by stabbing, sparked much debate and controversy. Some theories about him at the time linked him with the grand ducal House of Baden to be the hereditary “Prince of Baden”. Nevertheless, these have long since been rejected by professional historians. On the other hand, Kaspar Hauser fits into the contemporary European image of the “wolf child“, despite the fact that he almost certainly was not one. As a result, his story inspired numerous works.

Well known in Germany

If you are not a native German you might have probably never heard of the foundling known as Kaspar Hauser. In Germany, well among the people of my generation, the story of the foundling Kaspar Hauser is very well known, because it is and was always a big mystery and also subject to conspiracy theories. So, let me tell you more about the strange case of Kaspar Hauser.

Appearing out of the Blue

It was on May 26, 1828, that a strange teenage boy appeared out of the blue in the streets of Nuremberg, Germany. He carried a letter with him addressed to the captain of the 4th squadron of the 6th cavalry regiment, Captain von Wessenig with the heading ‘From the Bavarian border / The place is unnamed / 1828‘. The anonymous author said that the boy was given into his custody as an infant on 7 October 1812 and that he instructed him in reading, writing and the Christian religion, but never let him “take a single step out of my house“. Enclosed also was a letter that stated that his name was Kaspar, that he was born on 30 April 1812 and that his father, a cavalryman of the 6th regiment, was dead. A shoemaker named Weickmann took the boy to the house of Captain von Wessenig, where he would repeat only the words “I want to be a cavalryman, as my father was” and “Horse! Horse!” Further demands elicited only tears or the obstinate proclamation of “Don’t know.” He was taken to a police station, where he would write a name: Kaspar Hauser. He showed that he was familiar with money, could say some prayers and read a little, but he answered few questions and his vocabulary appeared to be rather limited.

Speculation Began

He spent the following two months in Vestner Gate Tower in the care of a jailer named Andreas Hiltel. He was in good physical condition, but appeared to be intellectually impaired. He refused all food except bread and water. At first it was assumed that he was raised half-wild in forests. But Kaspar told, for as long as he could remember he spent his life totally alone in a darkened cell about two metres long, one metre wide and one and a half high with only a straw bed to sleep on and a horse carved out of wood for a toy. He claimed that he found bread and water next to his bed each morning. Hauser claimed that the first human being with whom he ever had contact was a mysterious man who visited him not long before his release, always taking great care not to reveal his face to him. This man, Hauser said, taught him to write his name by leading his hand. Before taking him to Nuremberg, the stranger allegedly taught him to say the phrase “I want to be a cavalryman, as my father was“, but Hauser claimed that he did not understand what these words meant. Of course, this tale aroused great curiosity and made Hauser an object of international attention. Rumours began to circulate that he might be related to the Grand Duke of Baden, to whom he bore a startling resemblance, but there were also claims that he was an impostor. Speculation began to grow that he was indeed the son of Karl, Grand Duke of Baden, and Stephanie de Beauharnais, adopted daughter of Napoleon I of France. The couple had had a male child who was believed to have died.

Pencil drawing by Kaspar Hauser, 1829

Assassination Attempt

Hauser was given into the care of Friedrich Daumer, a schoolmaster and speculative philosopher, who taught him various subjects and who thereby discovered his talent for drawing. He appeared to flourish in this environment. Daumer also subjected him to homeopathic treatments and magnetic experiments. Kaspar began to write his autobiography and he proudly showed it to his numerous visitors. This, perhaps. was considered too dangerous an activity by his enemies. On October 17, 1829, a hooded man tried to kill him with a large knife. He only succeeded in giving the young man a long gash in the forehead. The apparent assassination attempt further fuelled rumors of Kaspar’s possible close connection to the House of Baden.

Lord Stanhope Inquiries

A British nobleman, Lord Stanhope, took an interest in Hauser and gained custody of him late in 1831. He spent a great deal of money attempting to clarify Hauser’s origin. In particular, he paid for two visits to Hungary hoping to jog the boy’s memory, as Hauser seemed to remember some Hungarian words and had once declared that the Hungarian Countess Maytheny was his mother. Hauser failed to recognize any buildings or monuments in Hungary. A Hungarian nobleman who had met Hauser later told Stanhope that he and his son had a good laugh when they recollected the strange boy and his histrionic behavior. Stanhope later wrote that the complete failure of these inquiries led him to doubt Hauser’s credibility.

Stabbed in the Chest

On December 14, 1833, Kaspar was lured to a park on the promise of receiving information about his background. He was stabbed in the chest by a stranger. He managed to get home, but died three days later at the age of only twenty-one. Hauser was buried in the Stadtfriedhof (city cemetery) in Ansbach, where his headstone reads, in Latin,

“Here lies Kaspar Hauser, riddle of his time. His birth was unknown, his death mysterious. 1833.”

King Ludwig I. offered the extraordinarily high sum of 10,000 guilders as a reward for the capture of a possible perpetrator, but without result. After completion of the investigations on September 11, 1834, the Ansbach District and City Court took the view that one could not avoid “the justified doubt as to whether a murder was committed by a third party against Hauser, whether a crime was committed against him at all”. Police Council Merker decided in another paper in favor of “Self-wound without intention to kill”. On his deathbed, Kaspar himself told Father Fuhrmann: “Why should I have anger or hatred or resentment for people, they did nothing to me.“

The Mystery remains

So, was Kaspar Hauser really a royal descendant? In 2002, the Institute for Forensic Medicine of the University of Munster analyzed hair and body cells as well as clothing said to have belonged to Kaspar Hauser. They were compared to DNA samples from Astrid von Medinger, a descendant of Stephanie Beauharnais, who would have been Kaspar’s mother, if he were indeed the true prince of Baden. There was a 95% match. The House of Baden refuses to comment on the Hauser matter and does not allow any medical examination of the remains of Stéphanie de Beauharnais or of the child that was buried as her son in the family vault at the Pforzheimer Schlosskirche. Thus, the story still remains a mystery…

Kasper Hauser – Child of Europe. Terry Boardman. Full Version, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Die umstrittene Geschichte eines Findelkindes at Zeit Online

- [2] Anselm von Feuerbach: Caspar Hauser, Boston 1832

- [3] Lost Prince. The Unsolved Mystery of Kaspar Hauser

- [4] Andrew Lang: The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser

- [5] “Hauser, Kaspar“. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- [6] Kaspar Hauser at Wikidata

- [7] Werke von und über Kaspar Hauser in der Deutschen Digitalen Bibliothek

- [8] Kasper Hauser – Child of Europe. Terry Boardman. Full Version, skyarcher @ youtube

- [9] Hanns Hubert Hofmann: Hauser, Kaspar. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 8, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-428-00189-3, S. 119 f

- [10] W. Höchstetter: Hauser, Kaspar. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 11, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1880, S. 89–92.

- [11] Philip Henry Earl Stanhope: Tracts Relating to Caspar Hauser. Hodson 1836.

- [12] Timeline of Imposters, via DBpedia and Wikidata