Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-1884)

On July 10 1884, Prussian egyptologist and linguist Karl Richard Lepsius passed away. Lepsius is regarded as one of the founding fathers of scientific methods in archaeology. His plans, maps and drawings of tomb and temple walls are of high accuracy and reliability. In 1866 he found found the Canopus decree at Tanis. Being written in two languages, it was a valuable cross-reference for the prior interpretation of the Rosetta stone by Champollion.[6]

Studying Greek and Roman Archaeology

Karl Richard Lepsius was born in Naumburg an der Saale, Saxony (Germany), the third son of Friedericke Glaser and Peter Carl Lepsius, Naumburg county commissioner. He studied Greek and Roman archaeology as well as archaeological philology and comparative languages at the University of Leipzig (1829–1830), the George Augustus University of Göttingen (1830–1832), and the Frederick William University of Berlin (1832–1833). After receiving his doctorate with a thesis entitled De tabulis Eugubinis in 1833, he travelled to Paris, where he attended lectures by the French classicist Jean Letronne, an early disciple of Jean-François Champollion and his work on the decipherment of the Egyptian language, visited Egyptian collections all over Europe and studied lithography and engraving.

Exctending Champollion’s Interpretation of Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Though attracted to the study of Egyptology, Lepsius actually resisted concentrating on the Egyptian language until the appearance of Champollion’s Grammaire égyptienne, when it became possible for him to undertake a systematized approach to its study. He made a comparison of the various systems of translation then in use, in an attempt to find to his satisfaction the one that was most likely to be correct. Then, in 1836, he visited Ippolito Rosellini in Tuscany, Italy, who had led the Tuscan contingent attached to Champollion’s expedition to Egypt in 1828-1829.[5] In a series of letters to Rosellini, Lepsius expanded on Champollion’s explanation of the use of alphabetic signs in hieroglyphic writing, emphasizing (contra Champollion) that vowels were not written.

Lepsius’ Expeditions to Egypt

In 1842, Lepsius was commissioned by King Frederick Wilhelm IV of Prussia to lead an expedition to Egypt and the Sudan to explore and record the remains of the ancient Egyptian civilization. Like the previous Napoleonic missions, the Prussian expedition was staffed with surveyors, draftsmen, and other specialists. It spent six months making some of the first scientific studies of the pyramids of Giza, Abusir, Saqqara, and Dahshur. They discovered 67 pyramids recorded in the pioneering Lepsius list of pyramids and more than 130 tombs of noblemen in the area. Working south, stopping for extended periods at important Middle Egyptian sites, such as Beni Hasan and Dayr al-Barsha, Lepsius reached as far south as Khartoum, and then traveling up the Blue Nile to the region about Sennar. After exploring various sites in Upper and Lower Nubia, the expedition worked back north, reaching Thebes in 1844, where they spent four months studying the western bank of the Nile with the Ramesseum, Medinet Habu, the Valley of the Kings, and another three on the east bank at the temples of Karnak and Luxor, attempting to record as much as possible. Afterwards they stopped at Coptos, the Sinai, and sites in the Egyptian Delta, such as Tanis, before returning to Europe in 1846.

Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia

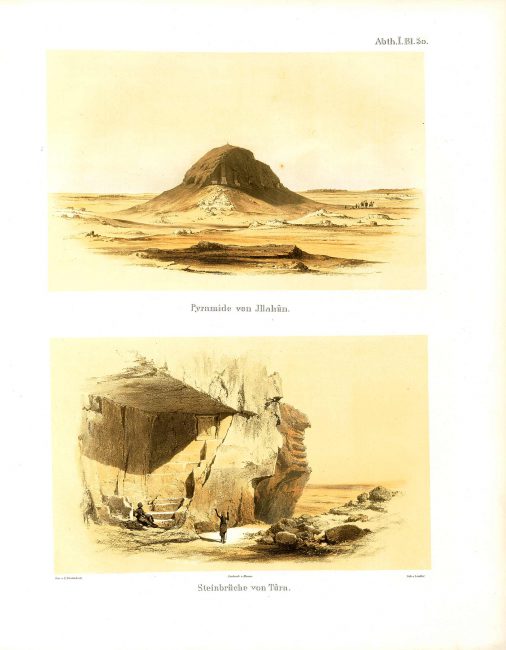

It is important to note that Lepsius’ first expedition did not only contribute to our knowledge of Egyptian monuments, the Egyptian language and mythology, but to the geography of this region. With a carefully chosen team of specialists, Lepsius was able to take more time and care in investigation and recording than anyone had before him.[5] Through an agreement with the Egyptian regent Muhammad Ali, Lepsius had a free hand to take along pieces – even original monuments – so that the Royal Museum suddenly became one of the largest collections of Egyptian antiquities. The chief result of this expedition was the publication of Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien (Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia)[3], a massive twelve volume compendia of nearly 900 plates of ancient Egyptian inscriptions, as well as accompanying commentary and descriptions, a work comparable in scale to the very formidable work of Napoleon’s Description de l’Egypte. These plans, maps, and drawings of temple and tomb walls remained the chief source of information for Western scholars well into the 20th century, and are useful even today as they are often the sole record of monuments that have since been destroyed or reburied.

Pyramid of Illahun and quarries of Tura from monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia

The Decree of Canopus

Upon his return to Europe in 1845, he married Elisabeth Klein in 1846 and was appointed as a professor of Egyptology at Berlin University, and the co-director of the Ägyptisches Museum in 1855. In 1866 Lepsius returned to Egypt, where he discovered the Decree of Canopus at Tanis, a trilingual inscription closely related to the Rosetta Stone, which was likewise written in Egyptian (hieroglyphic and demotic) and Greek. In 1881 Gaston Maspero discovered a first copy in Kom el-Hisn.[8] In the following years, only small or poorly preserved fragments from further excavations at various locations were added. In 1869, he visited Egypt for the last time in order to witness the inauguration of the Suez Canal.[5]

Further Achievements

Lepsius was president of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, the head of the Royal Library at Berlin, as well as the editor of the Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, a fundamental scientific journal for the new field of Egyptology, which remains in print to this day. While at the editorial helm, Lepsius commissioned typographer Ferdinand Theinhardt to cut the first hieroglyphic typeface, the so-called Theinhardt font, which remains in use today. Lepsius is considered the father of the modern scientific discipline of Egyptology. Much of his work is fundamental to the field. Lepsius even coined the phrase Totenbuch (“Book of the Dead“). Based on his work in the ancient Egyptian language, and his field work in the Sudan, Lepsius developed a Standard Alphabet for transliterating African Languages. His 1880 Nubische Grammatik mit einer Einleitung über die Völker und Sprachen Afrika’s contains a sketch of African peoples and a classification of African languages, as well as a grammar of the Nubian languages.

In 1873 Lepsius was appointed senior librarian (director) of the Königliche Bibliothek in Berlin; he held this office until his death on 10 July 1884 at age 73.

Chris Naunton, 200 years of Egyptology: the good, the bad and the ugly, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Karl Richard Lepsius, German egyptologist, at Britannica Online

- [2] Karl Richard Lepsius, in New World Encyclopaedia

- [3] Carl Richard Lepsius “DENKMÄLER AUS AEGYPTEN UND AETHIOPIEN”, Lepsius Project, Sachsen-Anhalt (in German)

- [4] Karl Richard Lepsius at Wikidata

- [5] Jimmy Dunn, Karl (Carl) Richard Lepsius – A Founder of Modern Egyptology, at Tour Egypt

- [6] Cracking the Code – Champollion and the Rosetta Stone, SciHi Blog, July 15, 2012.

- [7] Works of and about Karl Richard Lepsius (in German)

- [8] Gaston Maspero and the Sea Peoples, SciHi Blog

- [9] Stele of Canopus and the Rosetta Stone

- [10] Works of or about Kalr Richard Lepsius (in German), via Wikisource

- [11] Chris Naunton, 200 years of Egyptology: the good, the bad and the ugly, Council for British Archaeology @ youtube

- [12] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 481.

- [13] Jürgen Settgast: Lepsius, Karl Richard. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8, S. 308 f

- [14] Timeline of Egyptologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Very Helpful