The Universal-Lexicon published by Johann Heinrich Zedler is today considered the most important German-language encyclopedia of the 18th century.

On January 7, 1706, German bookseller and publisher Johann Heinrich Zedler was born. His most important achievement was the creation of a German encyclopedia, the Grosses Universal-Lexicon (Great Universal Lexicon), the largest and most comprehensive German-language encyclopedia developed in the 18th century.

Johann Heinrich Zedler – Background and Early Years

Johann Heinrich Zedler was born as the son of Johann Zedler, a shoemaker and citizen of Wroclaw, Silesia, today in Poland. Presumably without prior grammar school education, he began an apprenticeship with the Wroclaw bookseller Brachvogel. He then joined the business of the Hamburg bookseller and publisher Theodor Christoph Felginer and, after Felginer died in 1726, Zedler went to Freiberg in Saxony. There, in September, he married Christiana Dorothea Richter (1695-1755), sister of the publisher David Richter, who was eleven years older and came from a distinguished Freiberg merchant and council family. Probably equipped with the necessary financial means through his wife’s dowry, he opened a bookshop in Freiberg. Contrary to older literature, Zedler was already active as a publisher at this time. However, Zedler remained in Freiberg only for a short time.

Zedler’s first major publishing project: The dear man of God, Martin Luther. Title page of the first volume, Leipzig 1729.

First Major Publishing Works

Already in 1728, Zedler announced in the Leipzig newspaper Neue Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen, a new complete edition of the works of protestant reformer Martin Luther.[10] Unlike the previously available complete editions, the edition published by Zedler was not to contain a chronological, but a thematic compilation of Martin Luther’s writings. Thus, the work was to be more suitable for university use than any of the complete editions previously on the market. Zedler’s project was to be financed by the practice of prenumeration, which was common in the book trade of the 18th century. Interested parties were to pay in advance (“prenumerate“) for the first two parts by the Easter Fair of 1728 and receive a discount for doing so. Delivery was then to be made – against prenumeration on the following two parts – at the Michaelmas Fair in early October.

A Universal Lexicon

In 1730, Zedler announced in the Neue Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen his next major project – the Grosse vollständige Universal-Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste (Great Complete Universal Lexicon of All Sciences and Arts). Zedler thus intended to combine the numerous previously available reference works on the most diverse fields of knowledge into a single large work. This plan of a twenty-four-year-old young entrepreneur, who had not yet been in the publishing business for three years, meant a challenge to the established publishers in Leipzig. In 1704, Johann Friedrich Gleditsch had presented the Reale Staats- und Zeitungs-Lexicon – the encyclopedia aimed at the newspaper reader and thus the private household. In 1709, Thomas Fritsch had followed up with the Allgemeines Historisches Lexicon, the German-language equivalent of Louis Moréri’s Grand dictionaire historique – a major multi-volume project aimed at specialist libraries and scholars. In 1721, Johann Theodor Jablonski‘s Allgemeines Lexicon Der Künste und Wissenschafften was added – a handy work that was more thoroughly organized in terms of content than its compiling competitors. A number of smaller reference works for the general public complemented the spectrum with offerings that, like the Frauenzimmer-Lexicon, reached into the bourgeois household and the domain of women; of 39 encyclopedias published in the first half of the 18th century, 14 had been published by Gleditsch alone. All of these works were now in danger of being outbid by Zedler’s “universal” encyclopedia and driven from the market.

Some volumes of “Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste …” published by Johann Heinrich Zedler, binding of the time, in the Central Library of Solothurn, Switzerland

The Leipzig Printers’ Controversy

The first public reaction from the circles of established Leipzig publishers came five weeks after Zedler’s announcement. Following Zedler’s offer, Fritsch’s heirs also offered a free copy with the simultaneous subscription of twenty copies. In order to protect his encyclopedia, which was announced for the Easter Fair in 1731, against pirate printing, Zedler applied for a printing privilege from the Electorate of Saxony on September 13, 1730. Such work-related national privileges were usually granted for a period of five to ten years and were intended to protect the first printer within the state borders against foreign reprints. However, the Oberkonsistorium followed the reasoning of Fritsch and Gleditsch, rejected Zedler’s application, and imposed a fine of 300 talers on him on pain of confiscation.

Outsourcing the Production

In order not to jeopardize the delivery of the Universal Lexicon, Zedler moved production to neighboring Prussia. In Halle, he was in contact with the lawyer and university chancellor Johann Peter von Ludewig. In addition to his work at the university, Ludewig was also a leading member of the board of trustees for the orphanage in Halle. Apparently, it was he who arranged for the printing house attached to the orphanage to take over further printing of the Universal Lexicon. In order to be protected from reprints in Prussia as well, Zedler applied for a royal Prussian printing privilege as well as an imperial one at the same time. He received the imperial privilege issued to Charles VI on April 6, 1731, and the royal Prussian privilege only four days later.

A Difficult Start

Zedler was unable to meet the delivery date for the first volume of the Universal-Lexicon at the Easter Fair in 1731. Therefore, he announced that the delivery would take place at the Michaelmas Fair in October. At the same time, he announced his appointment as Royal Prussian and Electorate of Brandenburg Councillor of Commerce and assured that the company was now “under other privileges and freedoms of the very highest heads“. The reaction of the established Leipzig publishers to the appearance of the first volume was not long in coming. While the Michaelmas Fair was still in progress in 1731, they obtained from the Leipzig Book Commission a confiscation of all copies printed so far and not yet delivered. Zedler protested to the Leipzig Book Commission against the confiscation, but the Commission stuck to its decision. Thereupon the publisher turned to the Dresden Oberkonsistorium and achieved a partial success. In its decision the Oberkonsistorium granted him permission to supply his prenumerators with copies printed outside of Electoral Saxony. With this compromise, Zedler was able to continue his book production, but the transports incurred further costs. In his introduction to volume 1, Zedler himself claimed to have had the encyclopedia compiled by nine anonymous “muses.” Scholars continue to debate over how many or few collaborators he actually had. In fact, almost nothing certain is known about the individual authors of the encyclopedia.

The Book Lottery

In 1732, Zedler was dealt another blow: main editor of volume 1-2, Jacob August Franckenstein announced that he “may not have the least to do with the Zedlerische Universal-Chronica in the future because of some of the affections that had been aroused in him.” However, Franckenstein resigned from his position as editor of the Universal-Lexicon a short time later. Franckenstein died only two months later, on May 10, 1733. After his death, Paul Daniel Longolius (main editor volumes 3-18) took over the editorship of the Universal-Lexicon. In December 1733, Zedler introduced News on the Current State of War in his Cabinet magazine, increasing sales. But a few months later he faced competition from the Leipzig publisher Moritz Georg Weidmann with a competing magazine on news of the European states. In the spring of 1735 Zedler resorted to a new means to convert inventory into cash. In a specially printed brochure, he announced a book lottery. All participants would receive books, with a value equivalent to the amount they had paid, so there would be no losers. They would also get a ticket to a draw of valuable books. The draw would have brought new publicity to Zedler. Zedler pledged to donate a portion of the earnings to the Leipzig orphanage.

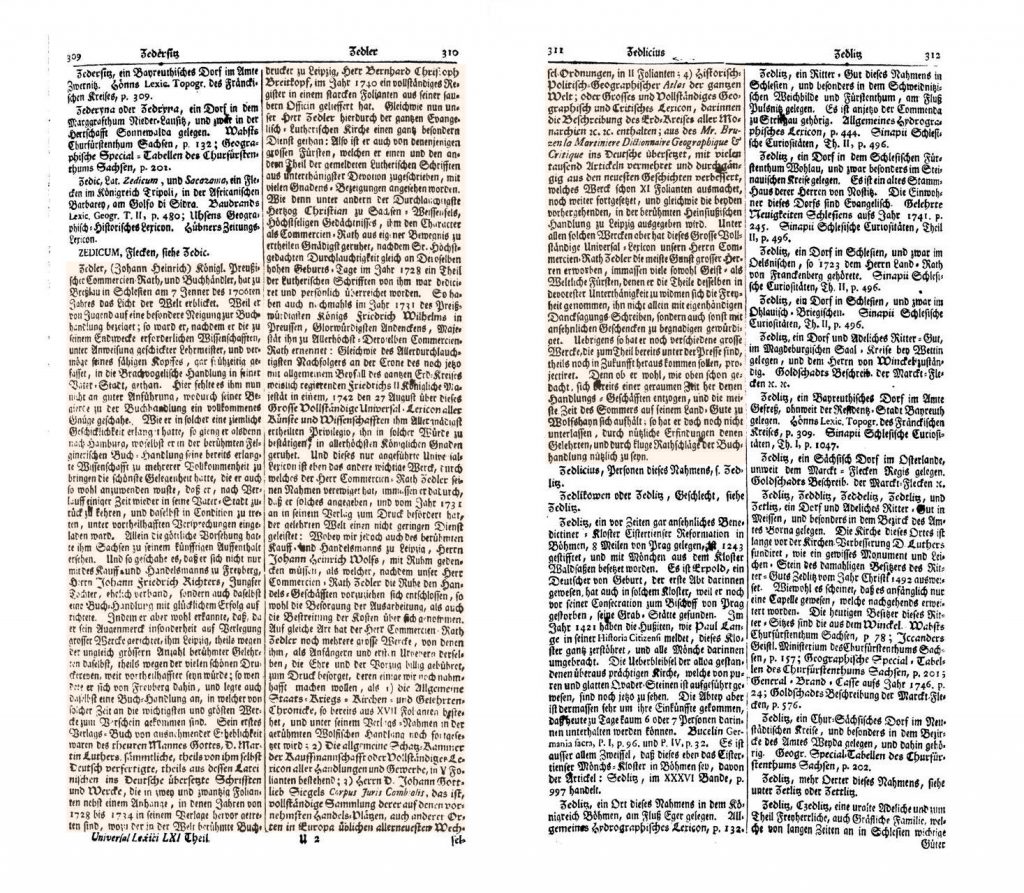

61st Volume of the Universal-Lexicon published in 1749, which contained the article on Zedler.

Collapse and New Start

The circumstances of Zedler’s financial collapse are largely in the dark. What is certain is that Zedler was no longer able to meet his payment obligations to his creditors after a certain point in time. The financial commitment of the Leipzig businessman Johann Heinrich Wolf enabled Zedler to make a new entrepreneurial start. On 5 August 1737, Zedler’s imperial privilege for printing the Universal Lexicon was suspended. As a former employee of Zedler, Longolius had the experience needed for publication of further volumes of the Encyclopedia. After Zedler lost the privilege he had been granted in January 1735, printer and publisher Johann Ernst Schultze from Hof, Bavaria, requested an imperial privilege in his own name. Thus, Schultze printed 17th and 18th volumes of the Universal-Lexicon and tried to sell them in Leipzig. From volume 19 on, the editorship of the Universal-Lexicon was taken over by the Leipzig philosophy professor Carl Günther Ludovici (main editor volumes 19-64 and supplements), who was a fellow student of Longolius. In contrast to Zedler, the Hofer printer Schultze subsequently published no further volumes of the Universal-Lexicon and had to sell his print shop to the Hofer Gymnasium in 1745 due to financial difficulties.

Retirement and Final Years

Johann Heinrich Zedler was increasingly marginalized after the financial takeover of his publishing house by Wolf, and after Carl Günther Ludovici took over the direction of the 19th and subsequent volumes of the Universal Lexicon. Ludovici made the bibliography at the end of each article more complete, made articles much longer and introduced biographies of living people. Zedler began to return to private life. In 1740 a number of Zedler’s products appeared under the name of the Leipzig bookseller and publisher Johann Samuel Heinsius. This began with a relaunch of Zedler’s Cabinet magazine, under a slightly altered title. Zedler probably created, or at least initiated further work. The Universal Lexicon article on Zedler published in 1749 says “he has several large works that are already being printed and should still come out“. Johann Heinrich Zedler spent most of his last years on his estate near Leipzig. He died on 21 March 1751 at age 45.

Significance

The Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon is sometimes considered the first modern encyclopedia in the German language. At the time, it was the largest printed encyclopedia in the Western world, and it remains one of the largest. It was originally supposed to be printed in about 12 volumes, an estimate later extended to 24, but it was finally printed in 64 volumes plus four supplements, with about 284,000 articles on 63,000 two-column pages. Ludovici had even intended to write a further four supplements. Also Diderot‘s [7] and d’Alembert’s [8] famous Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, 1751-1780) has plagiarized texts or text passages from Johann Heinrich Zedler’s Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste, for example, it was the source for many philosophical articles by Jean Henri Samuel Formey. Zedler’s work, for its part, had taken much from Johann Georg Walch’s Philosophisches Lexicon (1726).

Today, the Universal-Lexicon is mainly used as a historical source which, due to its conception, provides reasonably accurate information about the level of knowledge in various fields that can be assumed for the late 17th century and the first half of the 18th century. In addition, the study of this first large encyclopedia in the German language shows which conceptual innovations, but also which legal, financial and publishing problems such a project entailed. In the process, it is striking that many of the questions and problems that the publisher Zedler had to contend with in the first half of the 18th century are once again gaining relevance today in the age of digitization and the dissemination of knowledge on the Internet.

The controversial origins of the Encyclopedia – Addison Anderson, TED-Ed, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Zedlers Großes Universallexikon Online” [Zedler’s Great Universal Lexicon Online]. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- [2] Works by or about Johann Heinrich Zedler at Internet Archive

- [3] Müller, Winfried (2003). “Zedler, Johann Heinrich”. Sächsische Biografie. Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e. V., bearb. von Martina Schattkowsky.

- [4] Frank Weiske: Tagungsbericht Die gesammelte Welt. Wissensformen und Wissenswandel in Zedlers „Universal-Lexicon“. 18.11.2010–19.11.2010, Wolfenbüttel. In: H-Soz-u-Kult, 5. März 2011.

- [5] Zedler, (Johann Heinrich). In: Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexicon Aller Wissenschafften und Künste. Band 61, Leipzig 1749, Spalte 309–311.

- [6] The controversial origins of the Encyclopedia – Addison Anderson, TEDEd

- [7] Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, SciHi Blog

- [8] Jean Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert and the Great Encyclopedy, SciHi Blog

- [9] Johann Heinrich Zedler at Wikidata

- [10] Martin Luther – Iconic Figure of the Reformation, SciHi Blog

- [11] The controversial origins of the Encyclopedia – Addison Anderson, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of Encyclopaedists, via Wikidata and DBpedia