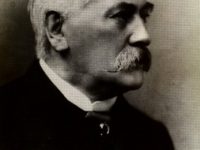

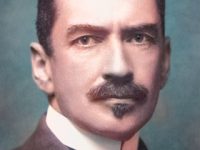

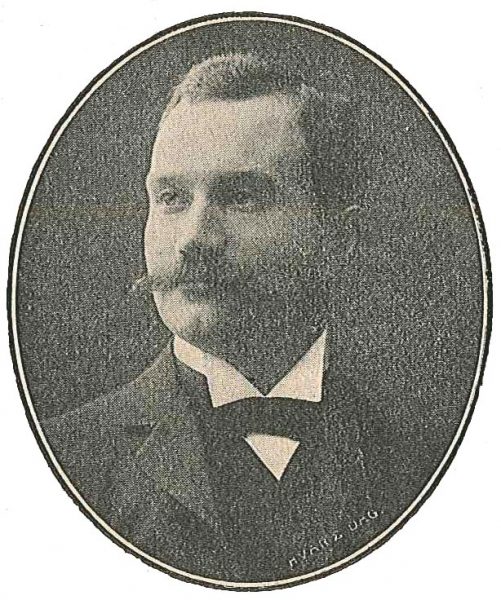

Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874-1960)

On July 3, 1874, Swedish archaeologist, paleontologist and geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson was born. Andersson is closely associated with the beginnings of Chinese archaeology in the 1920s. He laid the foundation for the study of prehistoric China. In 1921, at a cave near there, on the basis of bits of quartz that he found in a limestone region, he predicted that a fossil man would be discovered. Six years later, the first evidence of the fossil hominid Sinanthropu (Peking man) was found there.

Johan Gunnar Andersson – Early Expeditions and Solifluction

Johan Gunnar Andersson studied at Uppsala University. At the age of 25 he took part in an expedition to Spitsbergen led by Alfred Gabriel Nathorst. In 1898 Andersson already led his own expedition to Bear Island. From 1902 to 1903 he was deputy expedition leader on Otto Nordenskjöld’s Swedish Antarctic expedition. During his work on the Falkland Islands and the Bjørnøya, Anderson coined the term solifluction. In the original sense it meant the movement of waste saturated in water found in periglacial regions. However it was later discovered that various slow waste movements in periglacial regions did not require saturation in water, but were rather associated to freeze-thaw processes. The term solifluction was appropriated to refer to these slow processes, and therefore excludes rapid periglacial movements. In slow periglacial solifluction there are not clear gliding planes, and therefore skinflows and active layer detachments are not included in the concept.

Geological Advisor of the Chinese Government

In 1906 Andersson was appointed professor and head of the Swedish Geological Survey Authority. In 1914 he was appointed by the Chinese government as a geological advisor. Johan Gunnar Andersson’s office was the newly established Chinese National Geological Survey (Dizhi kaochasuo) and its director, Ding Wenjiang, soon became a friend. During this time, Andersson helped train Chinese geologists and discovered several iron ore deposits that were of great help to the emerging Chinese industry.

The Discovery of the Peking Man

In 1918, Johan Andersson visited Zhoukoudian and examined a region called Chicken-bone Hill because locals have misidentified the rodent fossils that are found in abundance there. Three years later he was led by local quarrymen to Dragon Bone Hill where he identified quartz that was not local to the area. Andersson relized that this may be an indication of the presence of prehistoric man. Andersson’s assistant Otto Zdansky was then given the task to excavate and lots of material over the next few years was sent to Uppsala for analysis. In 1926, when the Swedish Prince visited Beijing, Andersson announced the discovery of two human teeth, which were later identified as being the first finds of the Peking Man.[5]

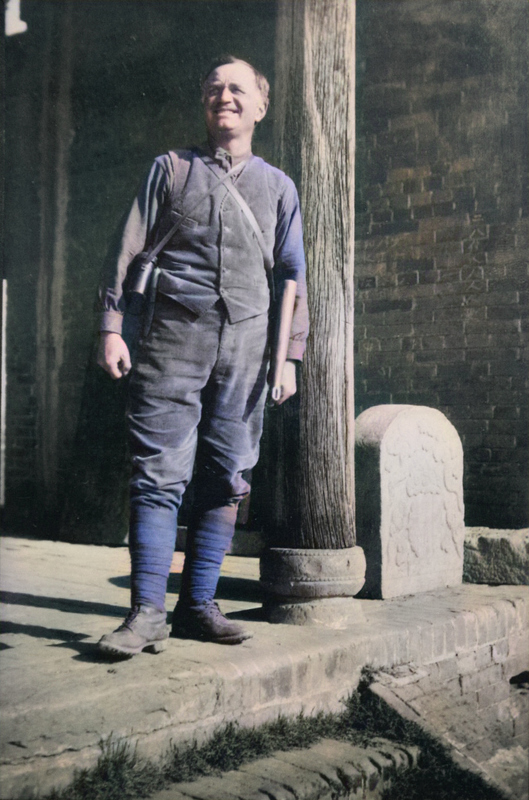

Gunar Andersson in China, 1920, Photo at East Asian Museum, Stockholm.

The Yangshao Culture

Further, Johan Andersson was able to discover the prehistoric Neolithic remains in central China’s Henan Province along the Yellow River together with his Chinese colleagues including Yuan Fuli. The remains were named Yangshao culture after the village where they were first excavated. This was an important development since the prehistory of what is now China had not yet been investigated in scientific archaeological excavations and the Yangshao and other prehistoric cultures were unknown. Johan Andersson’s well known book ‘Den gula jordens barn‘ (Children of the Yellow Earth) was published in 1932. It was translated into English, Japanese, and Korean.

Later Years

Andersson founded the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm in 1926 and served as its director until 1939. The Chinese part of the Andersson collections, according to a bilateral Sino-Swedish agreement, was returned by him to the Chinese government in seven shipments, 1927-1936. The last documentary evidence of these objects was a 1948 Visitors Guide to the Geological Survey museum in Nanjing, which listed Andersson’s Yangshao artefacts among the exhibits. Due to the civil war, the objects were believed to be lost long ago, but after major renovations at the Geological Museum of China, the successor to the Geological Survey’s museum, staff found three crates of ceramic vessels and fragments while reorganizing items in storage. In 2006, these objects featured in an exhibition at the Geological Museum on the occasion of its 90th anniversary, celebrating the lives and work of Andersson and its other founders.

In Sweden he was mainly known for his Chinese research and was subsequently nicknamed China-Gunnar. In China he was called An Tesheng (安特生). The Andersson Island and the Andersson-Nunatak in Antarctica are named in his honour. He died on 29 October 1960 in Stockholm, Sweden, at age 86.

Science Bulletins: Peking Man—Older Times, Colder Climes, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Johan Gunnar Andersson at Britannica Online

- [2] The Collaborative Dimension of Johan Gunnar Andersson’s Search for a Western Origin of China

- [3] The Reappearance of Yangshao? Reflections on unmourned artifacts

- [4] Johan Gunnar Andersson at Wikidata

- [5] Davidson Black and the Peking Man, SciHi Blog

- [6] Johan Gunnar Andersson at Reasonator

- [7] Science Bulletins: Peking Man—Older Times, Colder Climes, 2012, American Museum of Natural History @ youtube

- [8] Andersson, Johan Gunnar. In: Theodor Westrin, Ruben Gustafsson Berg, Eugen Fahlstedt (eds.): Nordisk familjebok konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi. 2. ed. vol 34: Supplement: Aa–Cambon. Nordisk familjeboks förlag, Stockholm 1922, pp. 203–205

- [9] Timeline of Swedish Archaeologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata