Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825)

On August 30, 1748, influential French painter in the Neoclassical style Jacques-Louis David was born. He is considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the 1780s his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in taste away from Rococo frivolity toward a classical austerity and severity.

“I want my works to bear the character of antiquity, so much so that, if it were possible for an Athenian to return to the world, they would appear to him as the work of a Greek painter.”

– Vie de David (1826), A. Th. (Thomé ou Thibaudeau), éd. Imprimerie J. Tastu, 1826, p. 13

Early years

David was born in the year when new excavations at the ash-buried ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum were beginning to encourage a stylistic return to antiquity. His father, a small but prosperous dealer in textiles, was killed in a duel in 1757, and the boy was subsequently raised by two uncles. After classical literary studies and a course in drawing, he was placed in the studio of Joseph-Marie Vien, a history painter who catered to the growing Greco-Roman taste without quite abandoning the light sentiment and the eroticism that had been fashionable earlier in the century. At age 18, the obviously gifted artist was enrolled in the school of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. After four failures in the official competitions and years of discouragement that included an attempt at suicide, David finally obtained, in 1774, the Prix de Rome, a government scholarship that not only provided a stay in Italy but practically guaranteed lucrative commissions in France.

Towards Classicism

While in Italy, David filled twelve sketchbooks with drawings that he and his studio used as model books for the rest of his life. He was introduced to the painter Anton Raphael Mengs, who opposed the tendency in Rococo painting to sweeten and trivialize ancient subjects, advocating instead the rigorous study of classical sources and close adherence to ancient models. Mengs’ principled, historicizing approach to the representation of classical subjects profoundly influenced David’s pre-revolutionary painting. Probably from the 1780s. Mengs also introduced David to the theoretical writings on ancient sculpture by Johann Joachim Winckelmann,[4] the German scholar held to be the founder of modern art history. In 1779, David toured the newly excavated ruins of Pompeii, the ruins of Herculaneum, and the Doric temples at Paestum, which deepened his belief that the persistence of classical culture was an index of its eternal conceptual and formal power.

The French Revolution and the Oath of the Tennis Court

When he returned to Paris in 1780, he was an artist already thoroughly imbued with the tenets of classicism. He was admitted to the French Academy in 1783 with his painting Andromache by the Body of Hector. The following year David returned to Rome in order to paint the Oath of the Horatii, the oath being administered to the Horatii by their father, who demanded their sacrifice for the good of the state, a work which was immediately acclaimed a masterpiece both in Italy and in France at its showing at the Parisian Salon of 1785. The painting reflected a strong interest in archeological exactitude in the depiction of figures and settings.[2] With the French Revolution in full swing, David for a time abandoned his classical approach and began to paint scenes describing contemporary events, among them the unfinished Oath of the Tennis Court (1791), glorifying the first challenge to royal authority by the parliamentarians of the period. He also concentrated on portraits of the martyred heroes of the fight for freedom, including the Death of Marat (1793).[2]

Jacques-Louis David: Oath of the Horatii (1784)

The First Painter to the Emperor

David had apparently long harbored great animosity toward the French Academy, perhaps because it had failed to fully recognize his talents when he had first submitted works for the Grand Prix competition. Though an honored member by the time of the Revolution, in 1793 he hastened its dissolution, forming a group called the Commune of the Arts.[2] A friend of Robespierre, David nearly accompanied him to the guillotine when the Jacobin fell from power in 1794. Imprisoned for 7 months, first at Fresnes and then in the Luxembourg, the artist emerged a politically wiser man.[3] It was at this time that David met Napoleon Bonaparte, in whose person he recognized a worthy new hero whom he promptly proceeded to glorify. The Emperor in turn realized the rich potential of David as a propagandist born to champion his imperial regime.

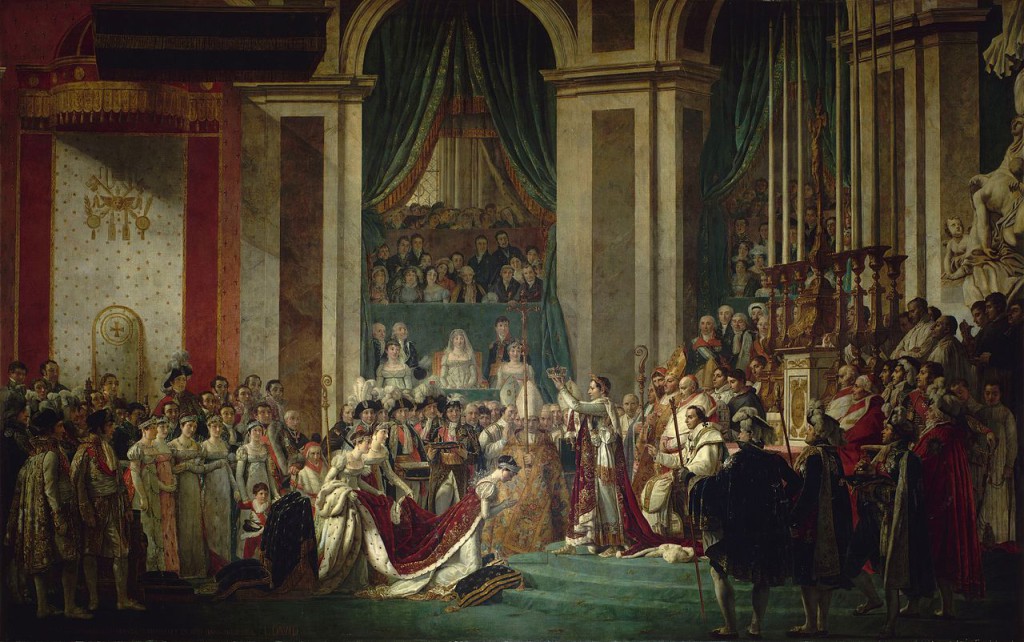

He appointed David “First Painter to the Emperor” in 1804 and enlisted many of his pupils to chronicle his triumphs. One of the works David was commissioned for was The Coronation of Napoleon (1806) in Notre Dame. David was permitted to watch the event. He had plans of Notre Dame delivered and participants in the coronation came to his studio to pose individually, though never the Emperor. The only time David obtained a sitting from Napoleon had been in 1797 after his early victories as a general in Italy.

The Coronation of Napoleon, (1806)

Exile and Death

After the fall of Napoleon in 1815, David was removed from the list of members of the institute and banished from France as a “Kingslayer”. An invitation from the King of Prussia – Frederick William III – to Berlin, where he was to take over the management of all art institutions, he refused and moved to Brussels, at least to stay near France. Here he continued painting despite his age and other misfortunes, exhibiting the resulting paintings in Ghent, Brussels and some also in Paris, but could not be persuaded to win the grace of the King of France, Louis XVIII, on the way of request. Ten years into his exile, he was struck by a carriage, sustaining injuries from which he would never recover.

Jacques-Louis David died on December 29, 1825, in Brussels, Belgium.

Travis Lee Clark, Lecture 08 18thC Neoclassicism Part 2 [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jacques-Louis David at Britannica Online

- [1] Jacques-Louis David at YourDictionary.com

- [3] “Jacques Louis David.”Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] The Prophet of Modern Archeology – Joachim Winckelmann, SciHi Blog

- [5] Travis Lee Clark, Lecture 08 18thC Neoclassicism Part 2, ARTH2710 History of Art from the Renaissance,Art History with Travis Lee Clark @ youtube

- [6] French painting 1774-1830: the Age of Revolution. New York; Detroit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Detroit Institute of Arts. 1975.

- [7] Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute 2005 exhibition, Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile

- [8] Jacques-Louis David at Google Arts&Culture

- [9] Jacques-Louis David at Wikidata

- [10] Timeline for Jacques-Louis David, via Wikidata