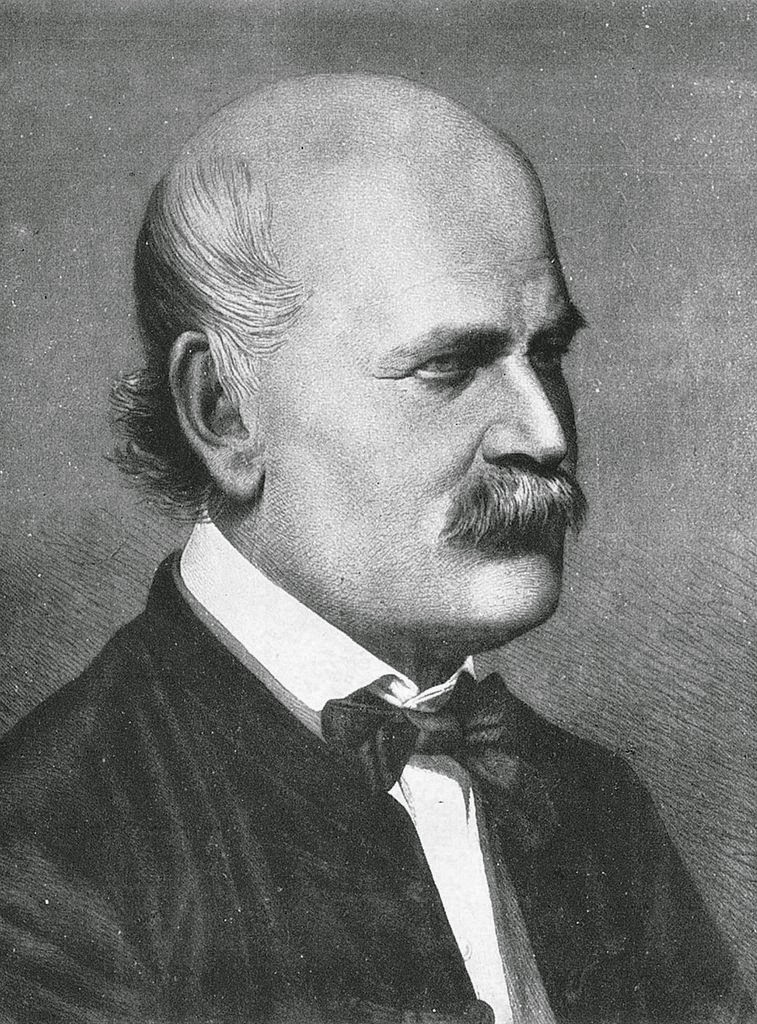

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818 – 1865)

On July 1, 1818, Hungarian physician of German extraction Ignaz Semmelweis was born. He is best known for his discovery of the cause of puerperal (“child bed”) fever and introduced antisepsis into medical practice by insisting on health workers rigorously handwashing between patients, and clean bed sheets.

Ignaz Semmelweis – Youth and Education

Ignaz Semmelweis was born in 1818 in the Tabán sub-district of Buda, Hungary, in 1818 as the 5th child of the specialty and colonial goods wholesaler Josef Semmelweis (1778-1846) and Theresa née Müller (1789-1844), who came from a wealthy family. Their parents attached great importance to a good school education for their children, as this enabled them to rise into the relevant social classes of the local intelligentsia. The father had all his sons enrolled in the Archbishop’s grammar school in Buda. Originally he was to become a military lawyer, so he studied philosophy[4] and law at the University of Pest from 1835 to 1837. In 1837 he came to Vienna to study law, but switched to medicine in 1838, continued his studies from 1839 to 1840 in Pest and from 1841 again in Vienna. In 1844 he graduated with a Master’s degree in obstetrics and in the same year with a doctorate in medicine.

Puerperal Fever and Hygieny

At the First Obstetrical Clinic of the Vienna General Hospital, where Semmelweis was employed, he had to examine patients each morning in preparation for the professor’s rounds, supervise difficult deliveries, and teach students of obstetrics. Back in the day, maternity clinics became quite common. Women could receive free medical care after giving birth, but had to function as subjects for the training of doctors and midwives. In Vienna, there were approximately two of those institutions while Semmelweis was still a young doctor. He began examining, why in one of the clinics the mortality rate due to puerperal fever was significantly higher than in the other. Semmelweis examined all the differences in techniques and even considered religious practices. He noticed that the clinic with the higher mortality rate offered a teaching service for students, the other instructed midwives only. The scientist also noticed that his friend, Jakob Kolletschka, died after getting cut during surgery and that his wound looked very similar to what he saw in his patients. Eventually, Semmelweis found out that the medical students carried “cadaverous particles” on their bodies and especially their hands after performing autopsies in the clinic. He concluded that these particles may cause childbed fever and introduced a policy of using a solution of chlorinated lime for washing hands before and after examining their patients.

“All students or doctors who enter the wards for the purpose of making an examination must wash their hands thoroughly in a solution of chlorinated lime which will be placed in convenient basins near the entrance of the wards. This disinfection is considered sufficient for this visit. Between examinations the hands must be washed in soap and water.”

– Ignaz Semmelweis

The Semmelweis Doctrine

This method became known as the “Semmelweis doctrine” and it was successful. Within a few months, the mortality rate due to puerperal fever shrank from 10% to 1.34%. However, not all of his colleagues enjoyed the new rules and Semmelweis even moved one step further. He proposed that the students performing dissections should not examine the living patients in the hospital beds in order to prevent the diease rather than ‘removing’ it. Unfortunately, the head of his department did not support the idea and refused to continue Semmelweis‘ contract at the hospital. In a huff, Semmelweis departed for Budapest immediately, where he was appointed head of the obstetrical service at the St. Rochus Hospital in Pest and managed achieve a mortality rate of 0.85% on a maternity service where puerperal fever had previously raged.

But soon forgotten

In 1861, Semmelweis published his findings titled as “The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Puerperal Fever” even though they were already announced to the profession in 1847 by his friend Ferdinand von Hebra, who was the editor of the Journal of the Royal Imperial Society of Physicians in Vienna. Many scientists began supporting Semmelweis’ doctrine and a lot of doctors, particularly in Germany, appeared quite willing to experiment with the practical hand washing measures that he proposed, but virtually everyone rejected his basic and ground-breaking theoretical innovation, that the disease had only one cause, lack of cleanliness. Soon Semmelweis’ doctrine was forgotten and ignored in the field of obstetrics, which disturbed Semmelweis incredibly while the mortality from puerperal fever on the services of some of these opposing Professors of Midwifery ranged as high as a barbarous 26% (for example in Würzburg). Semmelweis‘ eccentric behavior did definitely not make it any better. To a professor in Würzburg he wrote:

Your teaching (that the Würzburg epidemic of childbed fever is caused by unknown atmospheric influences or puerperal miasma is false), and is based on the dead bodies of lying-in women slaughtered through ignorance. . . I have formed the unshakable resolution to put an end to this murderous work as far as lies in my power so to do. . . (If you continue teaching your students this false doctrine), I denounce you before God and the world as a murderer, and the History of Puerperal Fever will not do you an injustice when, for the service of having been the first to oppose my life-saving Lehre, it perpetuates your name as a medical Nero.

Death by Sepsis

In 1865, Ignaz Semmelweis died from an infected wound on his finger, received during a gynecological operation. He suffered from an extensive sepsis leading to his early death. By a tragic irony, Semmelweis died from the same disease as his friend, Kolletschka, whose death provided the clue to the prevention of puerperal fever. Posthumously, Semmelweis’ doctrine gained acceptance widely. Louis Pasteur’s work offered a theoretical explanation for Semmelweis‘s observations, the germ theory of disease.[5] The “Semmelweis reflex” is on this day seen as a metaphor for a certain type of human behavior characterized by reflex-like rejection of new knowledge because it contradicts entrenched norms, beliefs or paradigms.

Semmelweis`Legacy

After Semmelweis’ death, the spraying of the surgical field with disinfectant carbolic acid, demonstrated by the Scottish surgeon Joseph Baron Lister (1827-1912) in 1867,[6] was introduced into surgery, resulting in a drastic reduction in surgical mortality. Asepsis is often attributed to him, although he had drawn his conclusions from those of Semmelweis. One generation of doctors later, the implementation of hygiene measures in women in childbed became common practice, and the scientific world became aware of the importance of Semmelweis’ findings.

Frank Snowden, 14. The Germ Theory of Disease, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever by Ignaz Semmelweis

- [2] Ignaz Semmelweis at the Semmelweis Society

- [3] The Myth and Cult of Ignaz Semmelweis: Constructing History of Science during the 20th Century at the Medical Journal of Australia

- [4] Semmelweis at Stanford

- [5] Louis Pasteur – the Father of Medical Microbiology, SciHi Blog

- [6] Joseph Jackson Lister – Perfecting the Optical Microscope, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis at Internet Archive

- [8] Ignaz Semmelweis at Wikidata

- [9] Frank Snowden, 14. The Germ Theory of Disease, Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600 (HIST 234), YaleCourses @ youtube

- [10] Hanninen, O.; Farago, M.; Monos, E. (September–October 1983), “Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, the prophet of bacteriology”, Infection Control, 4 (5): 367–370.

- [11] Semmelweis Society International. “Dr Semmelweis’ Biography”

- [12] Timeline of Hungarian Scientists, via DBpedia and Wikidata