St Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

Although her exact birthdate is uncertain, we dedicate today’s article to an extraordinary woman in science: German writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, Benedictine abbess, visionary, and polymath St Hildegard of Bingen. At a time when few women wrote, Hildegard, known as “Sybil of the Rhine“, produced major works of theology and visionary writings. She used the curative powers of natural objects for healing, and wrote treatises about natural history and medicinal uses of plants, animals, trees and stones. She is the first composer whose biography is known.

“O venerable father Bernard, I lay my claim before you, for, highly honored by God, you bring fear to the immoral foolishness of this world and, in your intense zeal and burning love for the Son of God, gather men [cf. Luke 5.10] into Christ’s army to fight under the banner of the cross against pagan savagery. I beseech you in the name of the Living God to give heed to my queries.”

— Hildegard von Bingen, Letter to Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux, 1146-47

Early Years

Hildegard most likely was born around the year 1098 to Mechtilde and Hildebert of Bermersheim, a family of the free lower nobility in the service of the Counts of Sponheim. Being the tenth and youngest child, Hildegard was sickly from birth. As Hildegard writes later in her Vita, she experienced visions from early age on. Her parents decided to offer her as an oblate to the church, but the date of Hildegard’s enclosure in the church is the subject of a contentious debate. According to her vita, Hildegard was only eight years old together with an older nun, Jutta, whom she assisted her in reciting the Psalms, working in the garden, and tending to the sick. Jutta was also a visionary and thus attracted many followers who came to visit her at the enclosure. It was Jutta who taught Hildegard to read and write.

Prioress in St Rupertsberg

Upon Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as “magistra” of the community by her fellow nuns. Abbot Kuno of Disibodenberg asked Hildegard to be Prioress, which would be under his authority. Hildegard, however, wanted more independence for herself and her nuns and asked Abbot Kuno to allow them to move to Rupertsberg. Upon his denial, Hildegard went over his head and received the approval of Archbishop Henry I of Mainz. Finally, Hildegard and about twenty nuns were able to move to the St. Rupertsberg monastery in 1150, where Volmar served as provost, as well as Hildegard’s confessor and scribe. In 1165 Hildegard founded a second monastery for her nuns at Eibingen.

Hildegard’s Visions

As Hildegard of Bingen reported, she already saw the first of her visions at age three, but it was not until she was five that she realized that she was experiencing visions. She used the term ‘visio’ to this feature of her experience, and recognized that it was a gift that she could not explain to others. Hildegard explained that she saw all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. While Hildegard continued to have many visions throughout her life, it was in 1141 when she was 42 years old, that she received a vision in which she received an order from God, to “write down that which you see and hear.” But she was hesitant to record her visions and struggled so much with herself that she became ill. It was between November 1147 and February 1148 at the synod in Trier that Pope Eugenius III heard about Hildegard’s visions, who granted her a papal approval to document her visions as revelations from the Holy Spirit giving her instant credence.

Visionary Theology

Hildegard’s works include three great volumes of visionary theology; a variety of musical compositions for use in liturgy, as well as the musical morality play Ordo Virtutum. Moreover, her writings include one of the largest bodies of letters (nearly 400) to survive from the Middle Ages, addressed to correspondents ranging from Popes to Emperors to abbots and abbesses. She authored two volumes of material on natural medicine and cures bedides various minor works, including a gospel commentary and two works of hagiography.

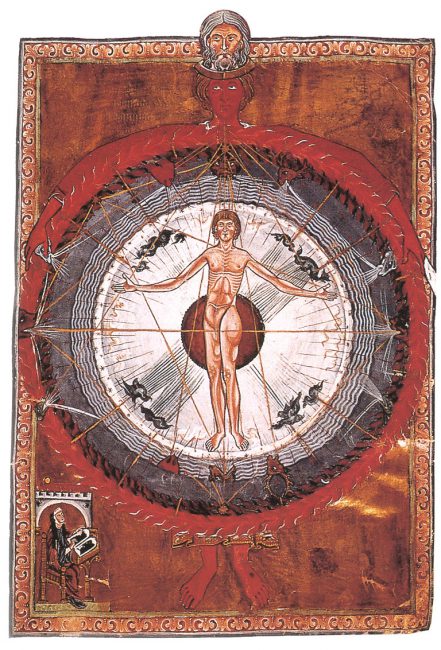

The Universal Man, Liber Divinorum Operum of St. Hildegard of Bingen, 1165

The Medicine of Nature

Hildegard’s most significant works were her three volumes of visionary theology: Scivias (“Know the Ways”, composed 1142-1151), Liber Vitae Meritorum (“Book of Life’s Merits”, composed 1158-1163), and Liber Divinorum Operum (“Book of Divine Works”, composed 1163/4-1172 or 1174). There, Hildegard first describes each vision, whose details are often strange and enigmatic, followed by her interpretation of the theological contents. Her main work Scivias (Know the ways) was written in a period of six years. This book contains 35 miniatures. These miniatures of theological content[ are painted with great skill in bright colors and serve mainly to illustrate the complicated and profound text. The original manuscript has been considered lost since the end of the Second World War. Hildegard’s very pictorial descriptions of her physical states and visions are interpreted by the neurologist Oliver Sacks as symptoms of a severe migraine, especially due to the light phenomena (auras) she describes.[5] Sacks and other modern scientists suspect that Hildegard suffered from a scotoma that caused these hallucinatory light phenomena.

Later Years

Already in 1151 there were new conflicts with clerical officials: Archbishop Heinrich of Mainz and his Bremen official brother Hartwig von Stade demanded that Richardis von Stade leave the new monastery. Richardis was the sister of the Archbishop of Bremen and was to become abbess of the Bassum monastery. Hildegard initially refused the release of her closest colleague and called in Eugen III. Nevertheless, the two archbishops finally prevailed and Richardis left the Rupertsberg monastery. After this agreement Archbishop Heinrich finally confirmed in 1152 the transfer of the monastery property, which had become very extensive due to Hildegard’s reputation. This increasing wealth also had an effect on the life of the community and aroused criticism. Thus several clergymen, but also leaders of other communities, for example the master Tengswich of Andernach, attacked Hildegard, because their nuns allegedly lived luxuriously against the Protestant advice of poverty and only women from noble families were accepted in Rupertsberg. Since the number of nuns in the Rupertsberg monastery was constantly increasing, Hildegard acquired the empty Augustinian monastery in Eibingen in 1165 and founded a daughter monastery there, which could be entered by non-nobles, and appointed a prioress there. Hildegard von Bingen died on September 17, 1179, at the age of 82.

Legacy

Today, she is best known to the public also because of her writings on medical science and healing. She wrote Physica, a text on the natural sciences, as well as Causae et Curae, describing her healing powers involving practical application of tinctures, herbs, and precious stones. In both texts Hildegard describes the natural world around her, including the cosmos, animals, plants, stones, and minerals. Due to her holistic and natural view of healing, Hildegard has also become a figure of reverence within the contemporary New Age movement.

On 17 September 1179, when Hildegard died, her sisters claimed they saw two streams of light appear in the skies and cross over the room where she was dying.

Margot Fassler talks about Hildegard of Bingen’s cosmos, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “St. Hildegard”. Catholic Encyclopedia</i>. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

- [2] Reconstruction of the monastery in Ruppertsberg

- [3] Women’s Biography: Hildegard von Bingen

- [4] Hildegard von Bingen at Wikidata

- [5] Oliver Sacks and his serious and at the same time exciting literary Case Studies, SciHi Blog

- [6] Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). “St. Hildegard“. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- [7] Book of Divine Works (Liber Divinorum Operum) I.1

- [8] Margot Fassler talks about Hildegard of Bingen’s cosmos, (2014), amsformusicology @ youtube

- [9] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Hildegard, St“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 461–62.

- [10] Abtei St. Hildegard / Abbey of St. Hildegard (Modern-day abbey in Eibingen, Germany)

- [11] Timeline of female saints, via Wikidata